BY NORMAN ROZEFF

“Build a better mousetrap, and they will buy it.” For centuries after the Spaniards subdued the Indians in Northeast Mexico and in what we now call the Lower Rio Grande Valley (LRGV) of Texas, the area north of the Rio Grande River remained sparsely populated and largely unproductive. That is, until, at the very beginning of the Twentieth Century, some visionary new settlers took the old cliché to heart.

They included such strong-willed individuals as Lon. C. Hill, Sam Robertson, and John Closner among others. Because Lt. William H. Chatfield, an officer stationed at Fort Brown, Brownsville, had begun his in-depth surveying of the LRGV in 1890, he documented an important topographical fact. It was gleaned that the Rio Grande River was at a higher elevation than the lands to its north. In short, if the river water could be pumped above the river’s bank its waters would flow northward by gravity.

Chatfield’s efforts to raise a million dollars to construct a gravity irrigation water canal taking water at Penitas and then across mid-Valley were unsuccessful despite his production of a slick, enticing 48-page over-sized booklet titled The Twin Cities, Brownsville, Texas and Matamoros, Mexico, of the border and the country of the Lower Rio Grande. In 1893, without reliable transportation to and from the Valley, the million dollars that he sought to implement his plan were a pipe dream.

The area extending from the river to around today’s Kingsville was called the Wild Horse Desert, both because of the huge number of wild horses that roamed in it and because of the many wind generated sand hummocks in it. It was not without its venturers however. The ending decades of the 19th Century saw considerable land transactions occur in the LRGV. Much of the region was once owned by descendants of land grantees. The Kings of Spain and later the Government of Mexico had deeded these grants over a long period starting in the mid-1700s. Because livestock raising was the primary use for the semi-arid land, grantees were usually awarded some frontage along the river although this could often be less than a quarter mile.

Grants, even narrow ones, would sometimes stretch up to 20 miles inland from the river. As the descendants grew in number and tax entities came into being under Texas laws, land was often posted for auctions by the counties due to tax delinquencies. They frequently were acquired at ridiculously low bids by unscrupulous insider politicians and lawmen. Also, attorneys who defended the land titles of cash-short grantees often accepted land in lieu of monetary payments.

A few enterprising individuals had over the decades created canals and pumping stations but only on a limited scale. These included, in 1875, George Brulay east of Brownsville; John Closner south of present San Juan in 1894; Judge Emilio Forto and the Longoria Brothers at Santa Maria, in 1897. The newer entrepreneurs quickly realized that any commodity production in the LRGV had no place to go as the area had no reliable port nor any railroad connections.

Then, led by Lon C. Hill, who had purchased, at rock-bottom prices, considerable acreage, among other sites, in and around today’s Harlingen, and what would become the town of Mercedes, a dynamic group of businessmen pursued investors to construct a railroad from Corpus Christi to the Valley and then east-west across the middle of the area. In 1903 they succeeded in inducing St. Louis investors into financing the construction. Railroad builder Uriah Lott then commenced construction of the line from Robstown to Brownsville in 1904.

By this time Hill has created the Lon C. Hill Town and Improvement Company and had laid a town along the Arroyo Colorado that he named Harlingen in honor of Lott’s ancestors from Harlingen, Holland.

By November 1903 a preliminary survey had commenced for the Sam Fordyce Branch (also called the Hidalgo Branch) rail line, 56 miles of track running west from Harlingen to Fordyce, west of what will become Mission. It is this line which opens the door for the settlement of numerous Valley towns such as La Feria, Mercedes, Weslaco, Alamo, San Juan, Pharr, McAllen, and Mission. Engineer Charley Ensminger is in charge initially but is so terrified by the wild territory that Chief Engineer Col. F. G. Jonah replaces him with W. T. Millington.

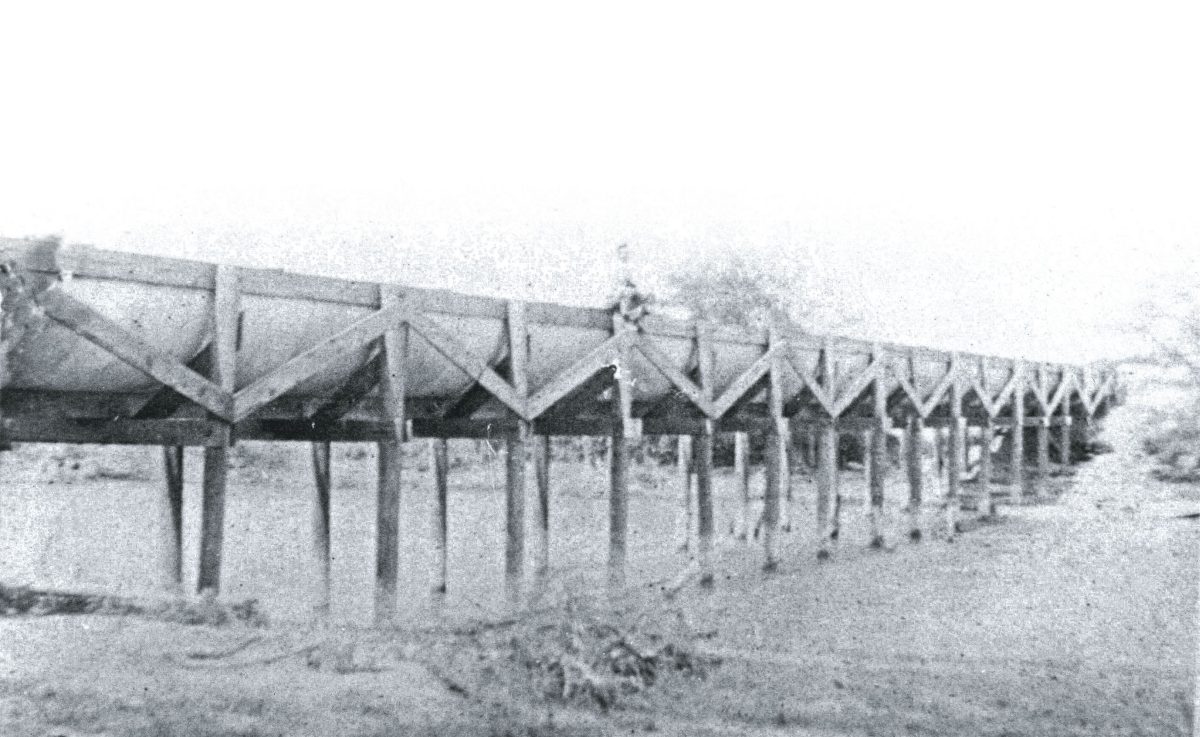

By May 1904 work on this branch began in earnest. Because of the level grades involved, the line was two and a half miles from completion by September 20,1904. It is on April 20, 1904 that the tracks from Robstown reached Harlingen, and on July 4, 1904 Brownsville celebrated the arrival of its first train ever from outside the Valley. The construction of the line’s longest bridge [that across the Arroyo Colorado at Harlingen] had incurred delays due to Arroyo Colorado flooding and the loss of the initial steel bridge abutments.

It was now that the entrepreneurs could construct their giant gravity flow canals. This first entailed considerable manual land clearing. The region had changed ecologically over time. The combination of overgrazing by sheep coupled with long-lasting periodic drought had allowed invasive vegetation to overcome the native prairie grasses. In their stead came deep-rooted mesquite and other xerophytic shrubs. Almost all the manual labor used to cut, pile, dry, and burn the tangled thicket vegetation was Mexican. For a time the larger collectible wood from trees was actually a welcomed harvest, for it provided fuel for the steam pumps along the river. It was, however, the discovery, in 1901, of oil at Spindletop that made feasible and expedited the pumps along the river, for this energy source was economical and readily available in contrast to ever-diminishing forestry products burned to generate steam.

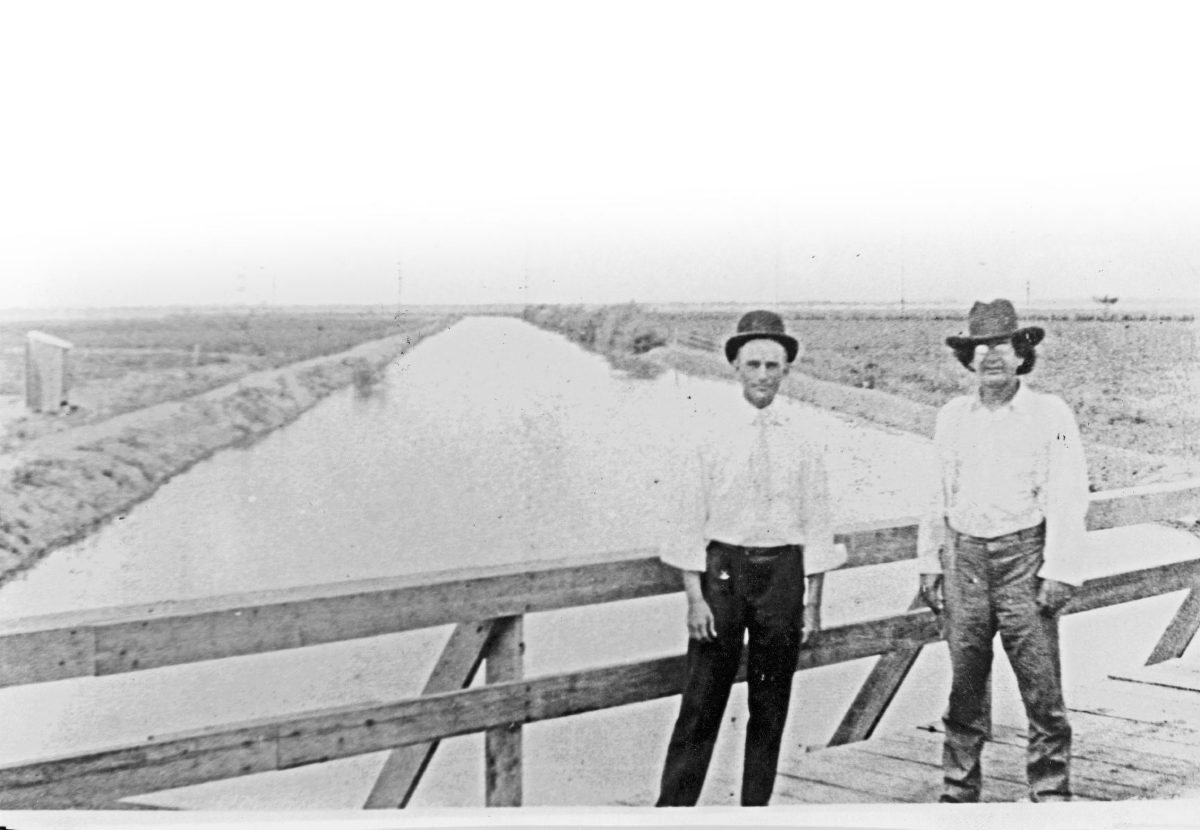

Hill commenced constructing his Harlingen Canal 9.75 miles south of the Arroyo Colorado in January 1907. By early September of that year the pumping station on the river filled the canal on its 18 mile journey to Harlingen. Today the only existing “old” pump house is that in the town of Hidalgo. It was erected in 1909 to fill the canals of the Louisiana-Rio Grande Canal Company. Its giant pumps and associated exhibits are open to visitors as the Old Hidalgo Pumphouse Museum.

Soon canals would be constructed to serve more of the Brownsville-Los Fresnos area as well as San Benito, La Feria, Mercedes, Llano Grande (later to be Weslaco), Donna, Pharr- San Juan, McAllen, and Mission. In order to recoup canal construction costs, land sales along these canals were highly promoted in the mid-West, and discounted train fares offered to entice prospective buyers. Acreage was either sold as cleared or, more economically, to a buyer to conduct his own clearing. To further attract buyers, they were shown four giant sugar mills that had been erected, one north of Brownsville, another in San Benito, a third in Harlingen, and the fourth just south of Donna. Today the sugar industry in the LRGV is represented by a single large modern mill west of Santa Rosa. The early area farmers experimented with a host of agricultural plants, including, profitably for a spell, broom corn and cabbage. Eventually Valley farmers concentrated their agricultural production primarily with citrus, cotton, grain sorghum, and various winter vegetables.

Visitors to the LRGV may visit a number of museum sites providing turn-of-the-20th Century regional history in Brownsville, Edinburg, and San Benito. One especially unique site is the Harlingen Arts and Heritage Museum. Here is to be found Lon C. Hill’s original 1904 house [the first to be built in Harlingen], his history, and numerous period artifacts. Nearby in the same patio area are the reconstructed 1884 Paso Real Stagecoach Inn, once located at the Arroyo Colorado ferry crossing west of Rio Hondo and Harlingen’s first hospital (1923).