BY NORMAN ROZEFF

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is next installment in an ongoing series on San Benito’s Sam Robertson. Read previous parts online at www.ValleyStar.com

To celebrate the Fourth of July in 1929, a San Benito committee conceived the idea of inviting the Gulf Coast Lines to participate. It was, after all, the 25th Anniversary of the arrival of the first passenger train into the Valley. The committee asked Col. Sam to suggest the names of individuals who might be honored.

In a letter to the committee, Sam responded with information on the line and a colorful description of the work, trials, and triumphs of the men and women he had come to love “for their fitness, courage, hardiness, and spirit.”

Among the people Sam suggested inviting was Mrs. May Lott-Stegman of Brownsville. She was the daughter of railroad visionary Uriah Lott.

Living contributors to the bonus that made the railroad to the Valley possible were, as Sam noted, Robert Driscoll, Mrs. Clara Driscoll-Seviere, Robert and Cesar Kleburg, John G. Kenedy, Jim Dishman, Lon C. Hill, John Closner, Oliver Hicks, Mrs Agnes Browne, James Landrum, A. A. Browne, Dr. Fred Combe, and especially Benjamin F. Yoakum of New York.

Sam continued his long list with the name of Col. F. G. Jonah, then chief engineer of the Frisco Line, but who had been an engineer during construction. Walter Ampter, then of La Feria, was noted to be the locating engineer on the job.

Sam included the living members of his Southern Construction Co. staff and made an effort to list the many individuals who actually did the physical labor as well as the women who left their comfortable homes to live in boxcars and support them.

He described the appearances of the many Mexican children in the camps and stated that he had located 20 of the construction crew children that he would like to include in the festivities.

He singled out Enedina Hernandez as a prominent member of the boomer outfit and who lived near the ice plant in San Benito.

Among the earth movers were Gene Hilary, John Hill, and Bill Dersett of Brownsville, Tom Lovett of San Juan, and John Ratcliffe of San Benito.

He mentioned Signora Marruetta Esparza de Rodriguez along with her husband as forty year settlers in the San Benito area and the builders of the first store and boarding house in San Benito with windows.

Senite Montalbo was pointed out as the first child born in San Benito after its settlement by Americans.

Sam then related that “Rafael Moreno, a cook with the engineers, lives in La Paloma and is the man who suggested the name of San Benito in honor of his former patron, Mr. Benjamin Hicks, who for many years owned Cipres Ranch, a part of the old San Benito tract.” Rafael was by then an “old patriarch”.

Robertson went on to tell of the first cars on the road carrying notables. The very first “varnished” car was that of Ben Johnston, a semi-invalid for many year. Sam characterized Ben as “one of the greatest contractors of his day.” The next “varnished” cars were six in number. They carried Frisco investor Benjamin Yoakum, Willie Kissam Vanderbilt, railroad speculator Sam Fordyce, St. Louis investors Tom West and W. K. Bixby, John Hays Hammond (famed railroad engineer), and others.

In an amusing sidelight, Sam recounted that on the 6th of June, 1904 the rails had reached Olmito and construction was delayed a day to cross the Brownsville Canal. The first commercial freight for Brownsville came to that point. It consisted of three loads of XXX Beer consigned to Teofilo Crixwell. This beer was then hauled by other means into Brownsville.

Lastly, Sam proudly relates that the steel reached Brownsville about June 10 and 5,000 people came out to see “our negoes lay track. With such an audience, and on the last day, the negroes put on a great show and threw down and spiked up two miles in about seven hours. This is a great record, but we laid 40 miles of the main line and 4 3/10 miles of side lines from April 1st to April 30th through the sand hills below Sarita. Sam concluded by giving credit to Lon C. Hill, John Closner, and Tom Hooks for guaranteeing the financing of the Hidalgo Branch by securing a 12,000 acre bonus.

The Gulf Coast Lines of the Missouri Pacific System printed a commemorative brochure with Robertson’s remarks. On its cover it paid tribute to all involved in the project to bring the outside world to the Valley. Its two paragraphs read:

“Honor to These Pioneers in the vital work of bringing transportation facilities to the Lower Rio Grande Valley and aiding materially thereby the development of this magic land’s wonderful possibilities.

Dedicated to those hardy souls whose foresight and labor in constructing the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico Railway struck the fire and fanned the flames of service which has served hundredfold until now the original 141 miles from Robstown to Brownsville are a part of the Missouri Pacific System with its 14,254 miles of public-serving rails.”

Ever the futurist, Col. Sam envisioned a vehicle highway from Corpus Christi to the south tip of Padre Island. This was before the Port Mansfield cut had been made. It would be a toll road. This never came to fruition as the shifting nature of Padre Island as effected by periodic storms and wind-drifted sands were too problematical. [Readers at this point are reminded that even in 1926 the King Ranch interests had not allowed a road to be constructed across the majority of its property.

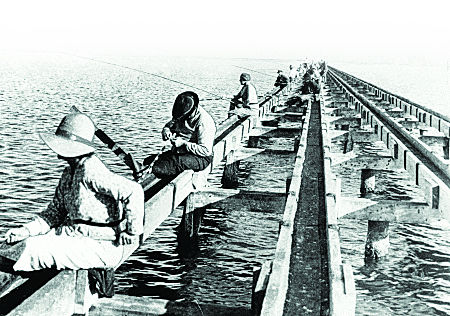

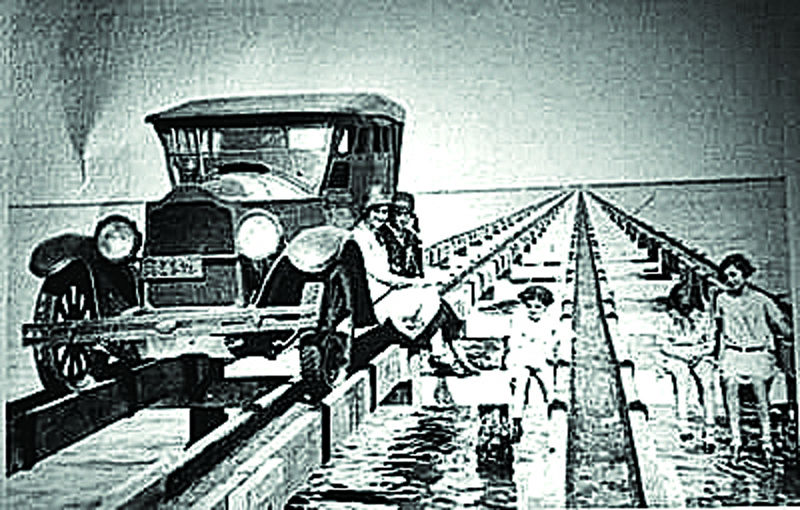

A road map of this year shows that the road south from Corpus Christi ended at Riviera where it turned west to Falfurrias. At this city it resumed its way south to Encino, Delfina, Edinburg, and Pharr. Just south of Delfina there was a secondary road east to Raymondville, where it continued south to Harlingen via Lyford, and Sebastian.] Robertson did however commence the project as the Berta Cabeza website relates: “Starting at [Flour Bluff] Aransas Pass on the Texas mainland, he constructed a causeway consisting of wooden troughs to accommodate the wheels of Model T’s. The span terminated on Mustang Island across the bay. Ferry service for the cars was provided from Mustang across a pass that no longer exists to Padre Island. Here began-or ended-Robertson’s Ocean Beach Toll Road.

The beach near the shoreline served as the roadbed. At dangerously soft spots and at the Old Shell Bank the route was reinforced with chicken wire and cement. The toll included ferry service for transporting cars between

South Padre Island was also to be built up with all manner of resort amenities. Robertson opened ferries at Port Aransas and at the south end of Padre Island. The latter was run by the Brazos de Santiago Pass Ferry Company organized by Sam. It docked at a rickety pier jutting from the extreme southern end of the island.

He did build a hotel, known as the Twenty-five Mile Hotel and later as the Surf Side Hotel about one-quarter mile north of the island’s tip. He built five houses about 45 north of the southern end of the island and a fifth house three miles from the causeway on the north. Although the unusual trough causeway boasted 1,800 cars the first month and 2,500 cars the second, interest began waning, after the 1929 Stock Market Crash.

By the next year, Robertson’s dream appeared doomed; he could not pay his debts. He sold his interest in the development and must have watched in horror as the 1933 hurricane destroyed all the structures on and leading to Padre Island. The purchasers on July 26, 1928 were the Jones Brothers and Parker, millionaires from Kansas City.