McALLEN — Coach Roy Swift often told a story about one of his McAllen High players who took time off from the team to attend to the burial of a relative.

On the day of the team’s next game, the player was waiting outside the gym when Swift arrived at 5 a.m. Swift noticed the player’s hands coated in dried blood and blisters and realized the teen had actually helped dig the grave.

The teenager asked Swift if he could play — a moment that figured in Swift’s pregame speeches for years to come.

“He would say: ‘If that kid was willing to do whatever it takes, what is your excuse?’” recalled Rick Treviño, the current Mercedes coach who was one of Swift’s assistants at the time.

Swift delivered many powerful pregame speeches during a more than 20-year coaching career that included seven seasons at Weslaco High and four at McAllen High — the final Valley stop for the former Pan American University forward.

Almost everyone who came in contact with him came away with the same feeling: He was a hardworking man who radiated optimism and made an imprint on Rio Grande Valley basketball that will last for generations.

Swift died on Jan. 13 due to complications from blockages in his arteries. He was 51.

BASKETBALL FROM START TO FINISH

Swift left McHi in 2010. He moved to Aurora, Colorado to be with the woman he fell in love with, Arleta Moon. They had a daughter, Monet N. Swift, who is now 2 years old.

Swift took a year off from coaching when Monet was born but had recently returned to the coaching ranks as a girls junior varsity coach at Hinkley High School in Aurora.

“When coach Swift first walked into our building this fall, what a breath of fresh air,” Hinkley athletic director Rodney Padilla said. “He was a man of character and a leader. … No matter how rough the seas were, he was always the same. And he developed a lot of relationships in a short period of time with kids and our staff.”

He was born in a little town called Alamo, Tennessee, on June 16, 1966. He moved to Detroit at a young age and saw plenty of his friends fall victim to the street life. But Swift wanted more, so he dedicated himself to learning everything he could about the game of basketball.

Though Swift left Detroit, the lessons he learned and things he saw came with him. Those memories later served as valuable lessons to the hundreds of players he coached through his career, the bulk of which was spent in the Valley.

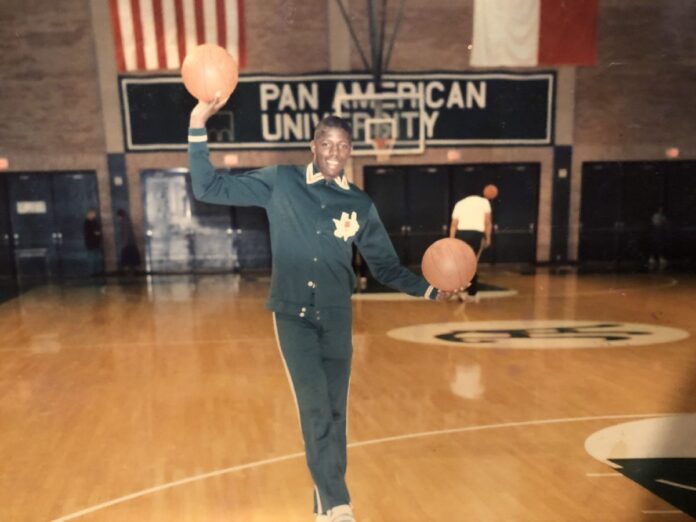

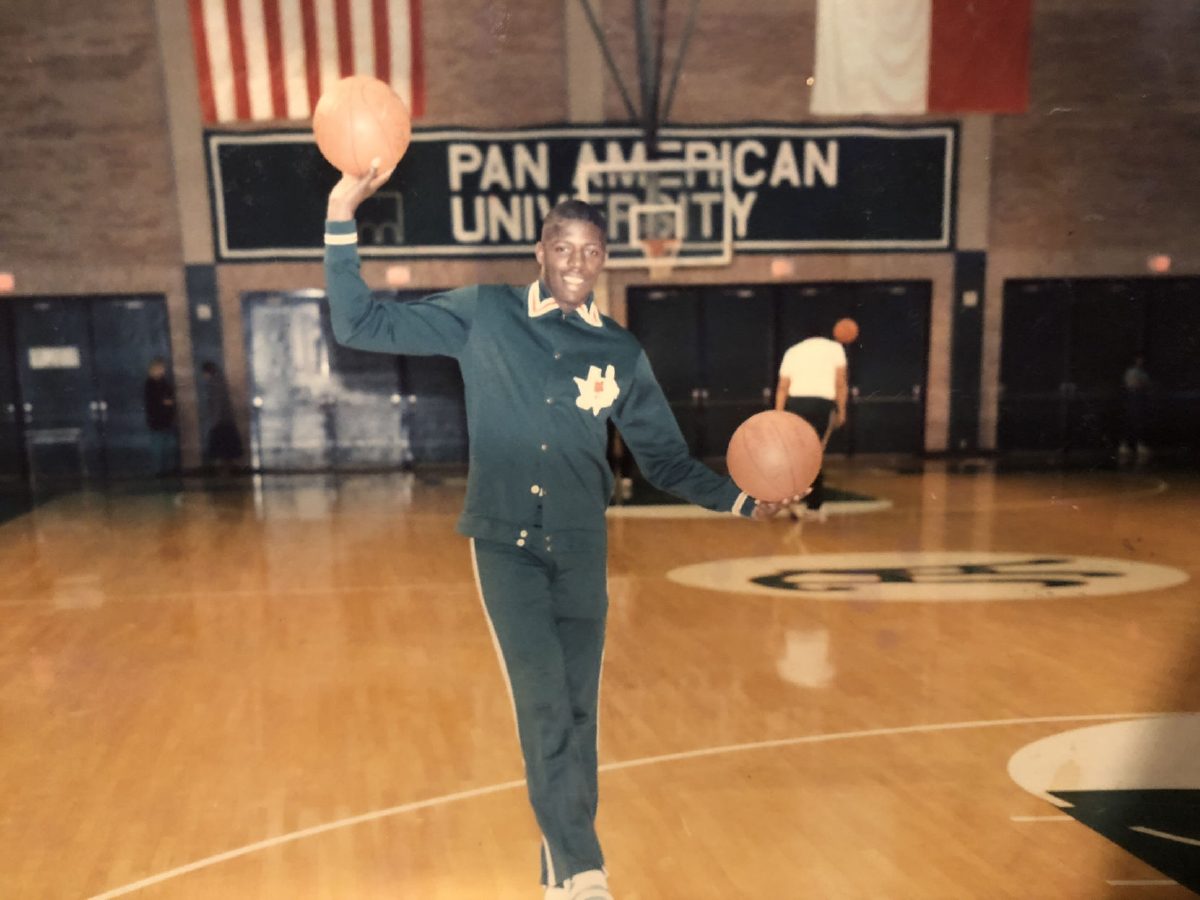

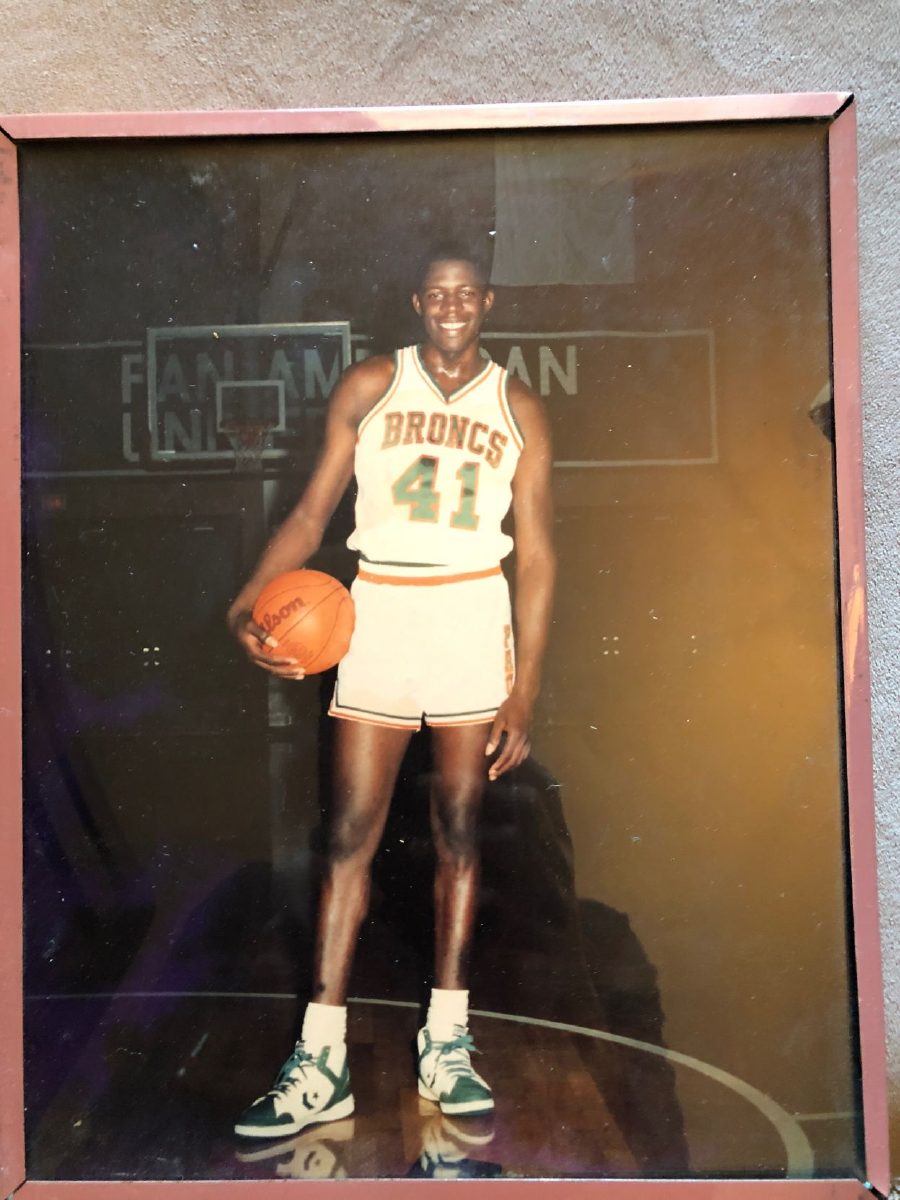

Swift was recruited out of Southwestern High School in Detroit to play basketball for Pan Am coach Lon Kruger in 1984.

“He was a great people person and a great teammate,” Kruger said. “He wasn’t the most naturally skilled athlete we had, but he worked harder than just about anybody. He played really hard, and he was a tenacious rebounder.”

During his sophomore year, Swift “hit a 17-footer at the buzzer to beat Stetson” for the team’s ninth win in a row, according to Edinburg reporter Greg Selber.

As a senior, Swift averaged 5.5 rebounds per game.

Swift played with Weslaco greats Art Castillo and Gabe Valdez during his time at Pan Am. Valdez later took over for Swift at Weslaco after Swift filled the job at McHi.

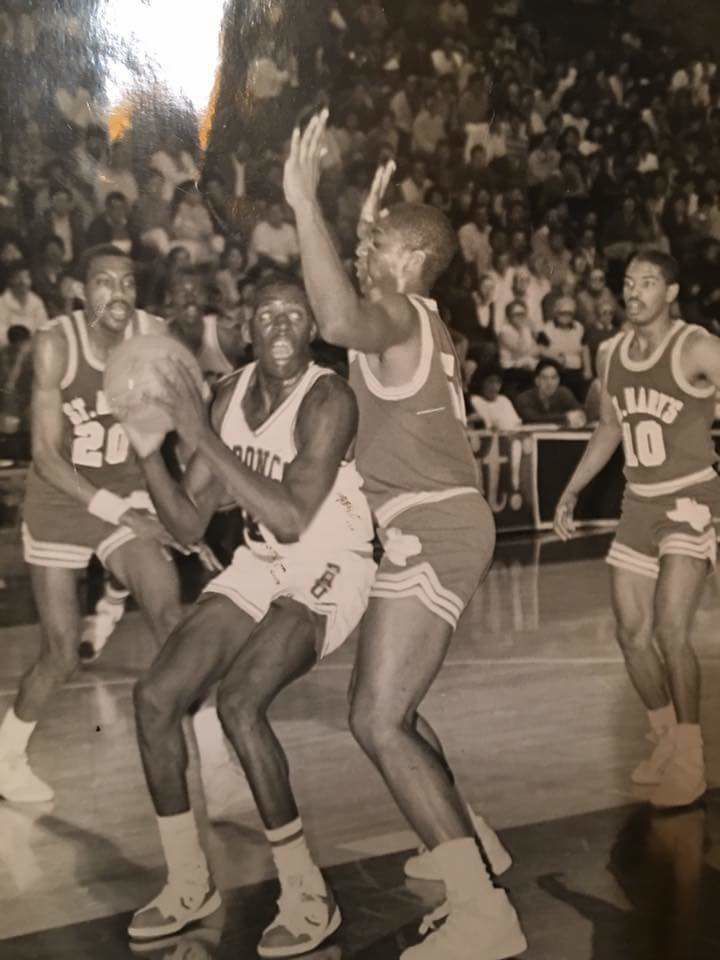

Swift began his coaching career in 1996 at Kenneth White Junior High School in Mission. After three years, he was brought on as the coach at Weslaco High. There, Swift hired current Harlingen South coach Brian Molina as an assistant.

Shortly after Molina was hired, Swift asked him to come to the gym to meet. When Molina arrived, the gym was eerily quiet, and all the lights were off. As Molina approached the locker room, a faint noise grew into a coherent sound: the lyrics of Whodini’s hit “Freaks Come Out at Night” echoing through the locker room. Swift was deep in thought over a dry-erase board, designing new plays.

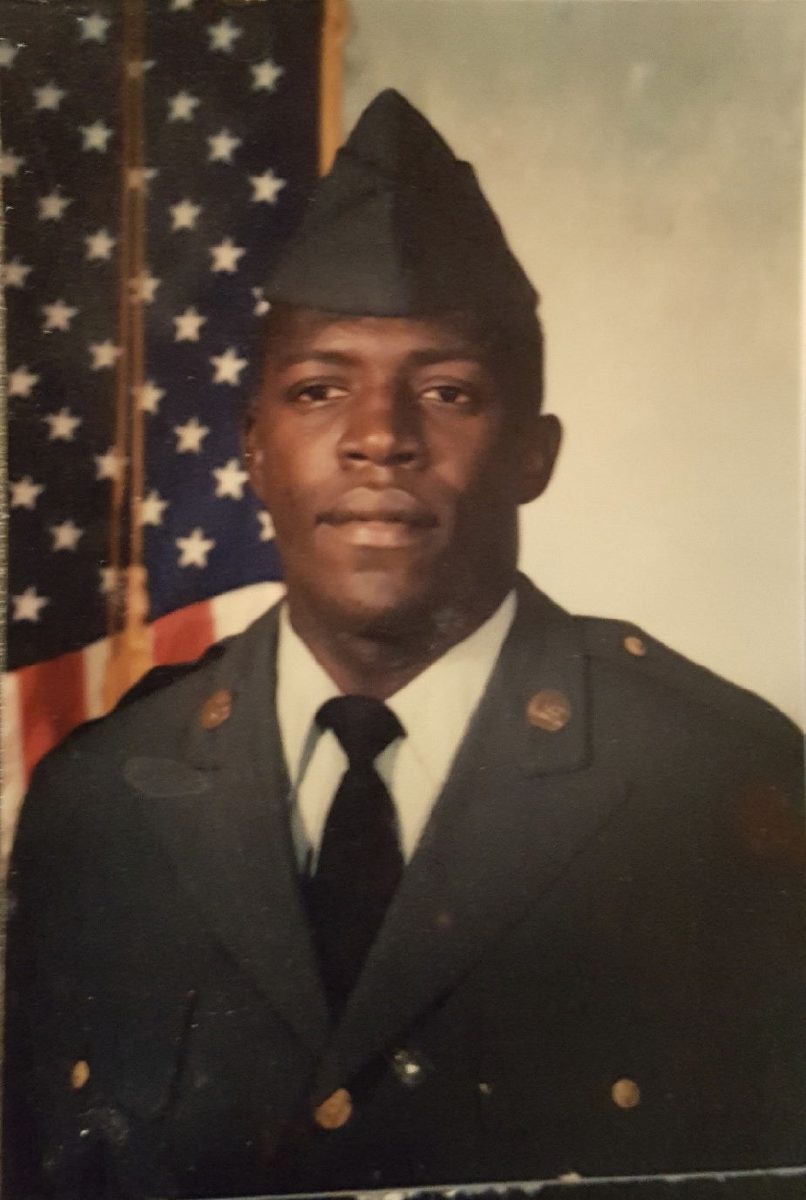

Swift was in his office by 4 or 5 a.m. every morning to begin preparations for his 6 a.m. practices. He enlisted in the Army Reserves just after he married, and that discipline showed in how he coached.

Swift watched hours of film, all the way down to the shot of his seventh or eighth guy off the bench. He wanted each of his players to leave his team better than when he got there.

“To follow that schedule day in and day out, to me, it is a lot of respect, and that was a key,” said Teresa Casso, who coached girls basketball at McHi during Swift’s years in the program. “Our boys respected coach Swift’s commitment to the team and commitment to making them better.”

A lot of players saw him as a father figure, Molina said, adding, “I looked at him as a mentor, and I know as a coach, I try to emulate everything that he taught me. Harlingen South is just an extension of Roy Swift.”

PREP FOR THE NEXT CHAPTER

Swift took great pride in seeing his former assistants and players go on to the next level or become head coaches.

Coaches closely associated with Swift include Treviño at Mercedes, Molina at Harlingen South, Jacob Alegria at South San Antonio and Eric Steinbrunner at PSJA Memorial. Swift also worked with former Valley coaches Joey Tate, Zeke Rodriguez and Mark Knuckles.

Swift’s imprint is evident in many different facets of these coaches’ techniques, Treviño said.

“Running liners; the way we talk to the kids; the way we prepare the kids; the way they dress; the way they get on the bus; plays; x’s and o’s,” Treviño said. “You will watch these teams, and you will watch the way they practice, and it is all from a foundation from coach Swift because of how well he did it.”

One of Swift’s players, Ryan Evans, went on to play at Schreiner University before joining the San Antonio Spurs financial office. Another player he coached, Cody Dukquits, became a strength and conditioning coach at Georgia Southern.

Swift stayed in contact with his players and assistants throughout the years. Even 15 or 20 years after they parted ways on the court, some called him almost daily.

“Coach Swift and I used to talk once a week,” Molina said. “I had just spoken to him about two or three days before he passed. … He was coming to the homecoming game there at UTRGV. … We have been struggling as a team, and he is one of the first people I turned to. He always found a way to make me feel better, reassure me that I am doing the right thing with the kids.”

During Swift’s first year at McAllen High, a freshman by the name of J.J. Avila quickly earned his trust, and the two became inseparable. In Swift’s later years, when he was living in Colorado, he attended some of Avila’s games at Colorado State. Avila had a standout college career and eventually ended up in the G League, where he now plays for the Texas Legends.

“They were like the best of buddies,” said Monique Swift, Roy’s eldest daughter and only child from his marriage.

On Jan.14, a day after Swift’s death, Avila posted on his Instagram:

“I’m waiting for this joke to be over … I’m not believing you’re actually gone. The man who took a group of boys and turned them into men. The man who put his faith in me and his career on the line from day one. The man who taught us how to be disciplined, how to work hard everyday, how there is always more we can give. The man who was more than a coach to us, but a mentor, a father figure, a man you never wanted to disappoint. He will be with us always, his wisdom will never leave us. The lessons he taught us will stay with us for life. I wish I would’ve told you I loved you from the bottom of my heart the last time you showed up unexpected in my living room a few months ago. I’m going to miss you with everything I have and I promise to continue to work hard every single day for you, Coach. Rest In Peace.”

FAMILY AND BASKETBALL

Swift met his ex-wife, Monica, at Pan Am. She became a track coach at Sharyland High after her collegiate career as a triple jumper and long jumper. Monique was born in 1993. She grew up as a coach’s daughter. She was often at Saturday practices, and she attended many games over the years.

Swift made the move from Weslaco to McHi before Monique’s eighth-grade year, which allowed Monique to play volleyball at McHi under longtime coach Paula Dodge.

Roy and Monica were together for 20 years in total and married for 16.

“Honestly, I think my parents were the perfect balance,” Monique Swift said. “My mom is more opinionated, and my dad was very calm.”

Roy was the adventurous one, so he always partnered with Monique on roller coasters while Monica watched from a safe distance.

Most who came in contact with Swift agreed that he was a relentless worker, but he still made time for his family.

“I think (my parents) had an understanding about how life was in season, but once the season was over, we took road trips. Our bonding time was very low maintenance,” Monique said.

Monique has fond memories of watching TV with her father.

“I distinctly remember falling asleep on my dad’s stomach, watching sports or things like that,” Monique said. “Family was very important to him, so he always made a point to balance his life with coaching and family.”

“Our family time was: dad had a game, mom and I would go and support,” Monique said. “And then we would go out for dinner after the game. That’s just how our lives were. … To see someone doing what makes them happy and then spending time together afterward was what made it all work.”

TIRELESS COACH

Swift was selfless, constantly worrying about his players or his team.

“He was always a really tough guy,” Treviño said. “He was always the guy who worked through any kind of pain. I remember when we were working one of our last years together, by the end of the season, he had walking pneumonia, because he didn’t rest. He would sleep three or four hours a day and be watching film and preparing. That’s just the way he was. He worked through everything.”

Swift lost his mother, Owanda Moody, and his older sister, Renona K. Howard, to cancer. Monique believes Roy didn’t want medical help because he was afraid of what the doctors would find. He was scarred by the losses he suffered.

“He had some blockage in his arteries. That doesn’t develop overnight,” Monique said. “The passing of his mother weighed on him. He took that close to heart, especially around the holidays, because she passed around the holidays. He always had a hard time dealing with it.”

Monique and other friends have wondered if his death could have been prevented. He played basketball in leagues with his colleagues through his early 40s, Monique said, and he golfed regularly. He seemed to be in good health before his passing, she said.

“Because I am in pharmacy school, I think about this differently,” Monique said. “I knew that there was a problem, but he just never wanted to address it. … I think it was a heart condition. … Like I said, that doesn’t develop overnight.”

SWIFT’S LEGACY

Swift’s death was such a surprise, and such a blow, because his energy was always so high and his positive outlook was so infectious.

“It is so hard to be around someone like that and not feel better,” Treviño said.

That positivity permeated his career and life. His love for family and sunny disposition left Monique with something many yearn for when a loved one dies: the knowledge that they loved you, and you loved them.

“He came (back to the Valley) in September,” Monique said. “He surprised me at work, because I didn’t know he was in town. We were able to have a nice dinner at a restaurant not too far from the house, and we just talked about school and when I would graduate.”

Monique said she still left some things unsaid.

Monique struggled seeing Swift with Moon, especially after they moved to Colorado. Monique said as a high school student, her emotions after the divorce were confusing. She developed a resentment toward the church. She said she had to work to rebuild parts of her relationship with her father.

“Every time he would call me he would ask, ‘Have you found a church yet?’” Monique recalled. “Before his passing, we were not able to have a conversation, and I think that has been one of the hardest parts to cope with. I told him I wanted to have a really big conversation with him, because I went to church and I had this epiphany, and I was ready to let go of, I guess, the bitterness that I had felt from my parents’ divorce. I wanted to talk to him. I didn’t get a chance to call him back, because I am busy with work and school. So it was a lot going on. I didn’t have a chance to talk to him the week of his passing. We were texting, but we didn’t get to talk.”

Anyone who worked with Roy Swift could see that he loved his family.

“Monique was his world,” Casso said. “He just cared tremendously for Monique. He was always so proud of her, and he was at all of her volleyball games. He was always there to put his arm around his little girl.”

During Swift’s time at McHi, he coached a physical education class for kids with special needs, Treviño remembered.

“The way he worked with us in practices was the same way he was out there with these guys,” Treviño recalled. “He would be having fun, and blowing the whistle and getting after it. … They would just hug his leg, and we would have to pull those guys off. You could tell he had a special relationship with those kids.”

One day, Swift was with his team working on a new play that was yet to be given a name. All of a sudden, one of his special needs students, Kyle, walked in and started talking to Swift excitedly. Swift stopped the practice to spend time with Kyle. When he returned, Swift said, “I know what we will call this new set: Kyle.”

Kyle and that McHi player with the blisters got to see the real Roy Swift: the Swift who Molina and Treviño learned from for years; the Swift who was in love with his youngest daughter, just as he loved Monique; the Swift who loved the Detroit Lions, Michigan and Michigan State, and always teased his friends about their favorite teams.

Memorial ceremonies for Swift took place across the country. He was buried in Detroit, and services were also held in Aurora, McAllen and Weslaco.

Roy Swift’s story spans generations, and his impact has changed hundreds of lives. At his core, Swift was exactly the man that Casso described.

“Coach Swift was totally dedicated to the game of basketball — to his work. He was very knowledgeable, very disciplined and very, very caring toward the young men he worked with.”