|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

He had just found out that Ken Paxton wanted $3.3 million to settle a lawsuit with a group of whistleblowers who’d accused him of corruption and retaliation. Leach, a Collin County Republican like Paxton, considered the Texas attorney general a friend — one he fiercely defended in the past.

But asking the Legislature to pony up the money was too much. On Feb. 10, he texted Michelle Smith, Paxton’s senior advisor, and urged the state’s top lawyer to come to the Capitol and publicly explain himself.

“Legislators have questions and we want answers. If we get the satisfactory answers, then all will be fine,” Leach wrote to Smith, according to copies of the messages The Dallas Morning News obtained through public records requests.

“I don’t think y’all understand how pissed members are, including many of your conservative friends in the house and senate. I don’t know a single legislator who believes taxpayers should be expected to be on the hook for this,” he added.

Smith balked.

“What happened to, ‘I will work with him until the day I die?” she responded in the text thread, urging Leach to speak directly with Paxton. “If he’s a friend get the full story.”

“The Christian thing to do is to ask what’s going on in Private. If you don’t like the answer then do whatever public,” she added later in that conversation.

“You’re really gonna go there with me?!” Leach fired back. “This is on Ken. Not on me. I’m doing my job. I will be calling a public hearing and he and I can have the conversation on the record.”

“You do you,” Smith replied.

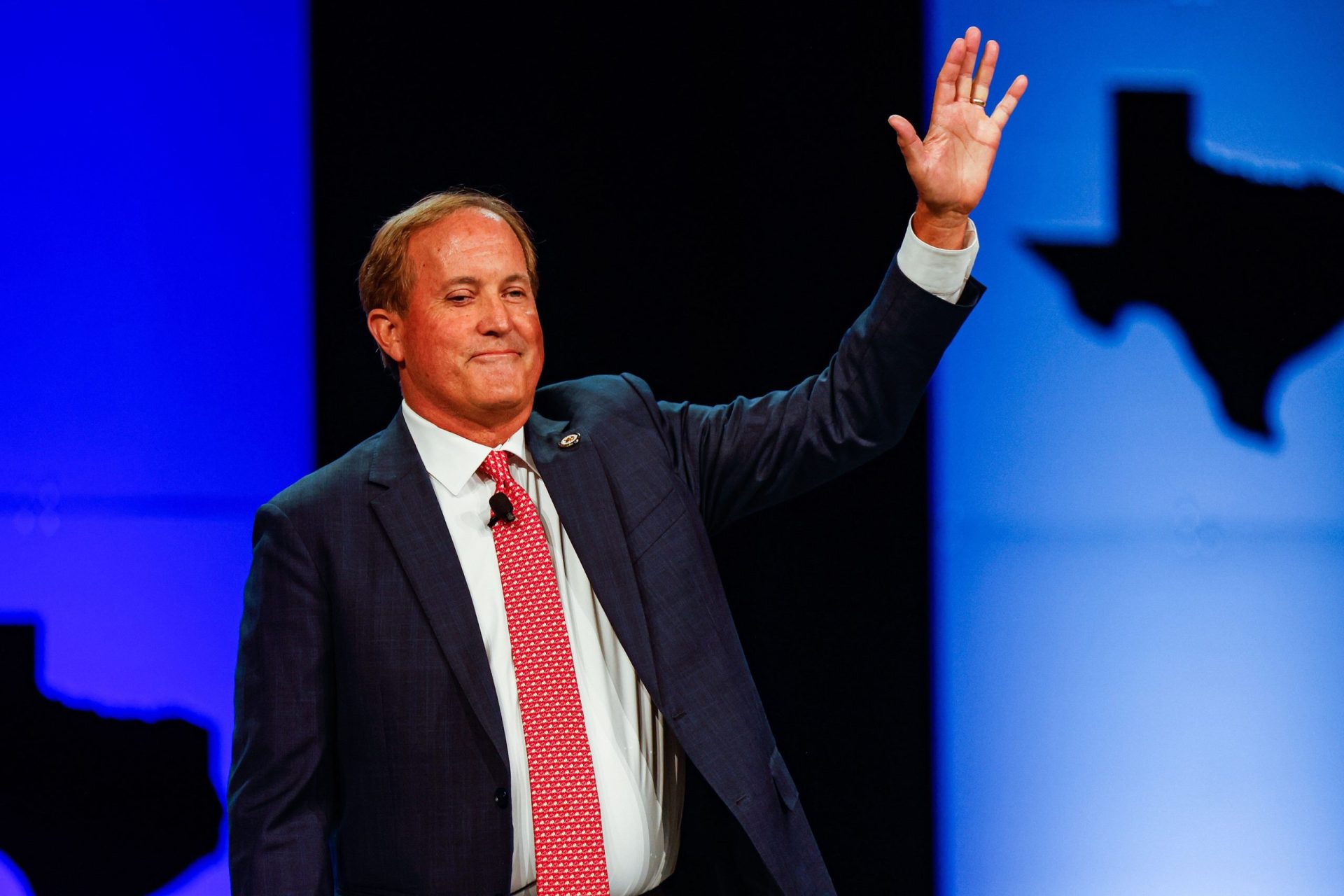

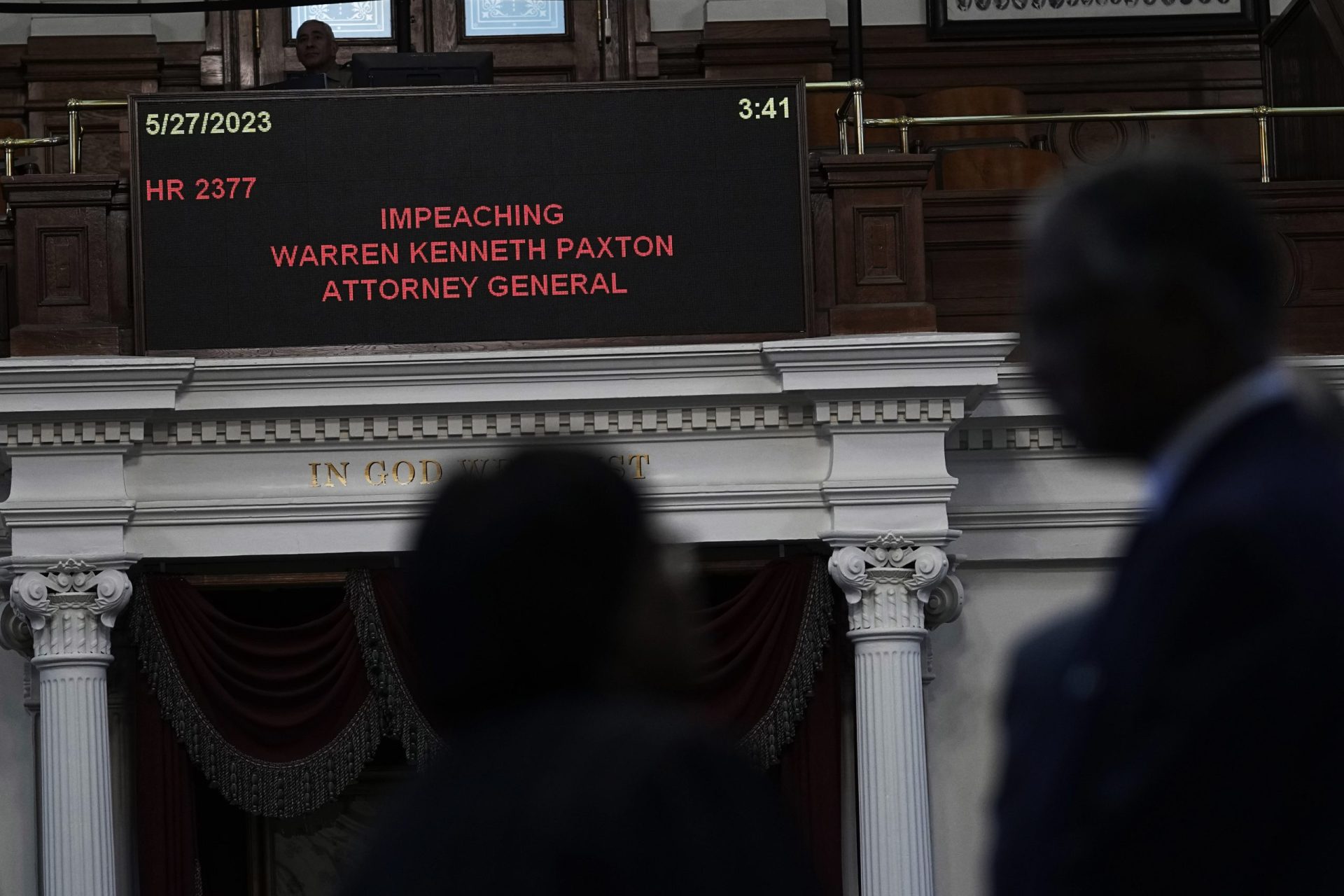

Spurred by the settlement funding request, a House ethics committee began reviewing the whistleblowers’ allegations against Paxton by March, according to its investigators. In late May, the House voted overwhelmingly to impeach Paxton based on the committee’s findings that the attorney general likely abused his power to help a campaign donor under FBI investigation.

Paxton’s lawyers argue their client was robbed of the chance to defend himself before he was impeached.

But the text exchanges between Leach and Smith reveal for the first time the extent to which the attorney general was urged, even warned, that he needed to defend the settlement to lawmakers.

On May 27, the day Paxton was impeached, Leach stood at the microphone on the House floor and said he’d invited the attorney general to appear before the committee he chairs. The committee held 12 meetings that year, Leach said, and Paxton never showed up.

On Sept. 5, the Senate will convene a trial to determine whether Paxton is removed from office.

Faced with the most significant opportunity to speak on his behalf, he appears to have chosen silence. His lawyers say the attorney general will refuse to testify during the trial.

“The House has ignored precedent, denied him an opportunity to prepare his defense, and now wants to ambush him on the floor of the Senate,” Tony Buzbee, a member of Paton’s legal team, said in a statement on July 3. “We will not bow to their evil, illegal, and unprecedented weaponization of state power in the Senate chamber.”

Paxton’s settlement

After Paxton’s impeachment, The News requested all communications exchanged this year between Leach, a key North Texas lawmaker, and Smith, who has long been one of the attorney general’s most dedicated allies.

Paxton’s agency produced 26 pages of text messages sent between Jan. 10 and June 11.

The records provide insight into discussions between Paxton’s inside circle and lawmakers leading up to the impeachment vote, and show that the attorney general was urged to personally and openly defend the settlement funding.

Smith did not return requests for comment for this story sent to her campaign email address. Representatives from the Office of the Attorney General and Paxton’s impeachment lawyers also did not respond to questions.

Leach and Dick DeGuerin, a lawyer hired to present the case against Paxton, both declined to comment citing a gag order placed on all parties to the impeachment trial.

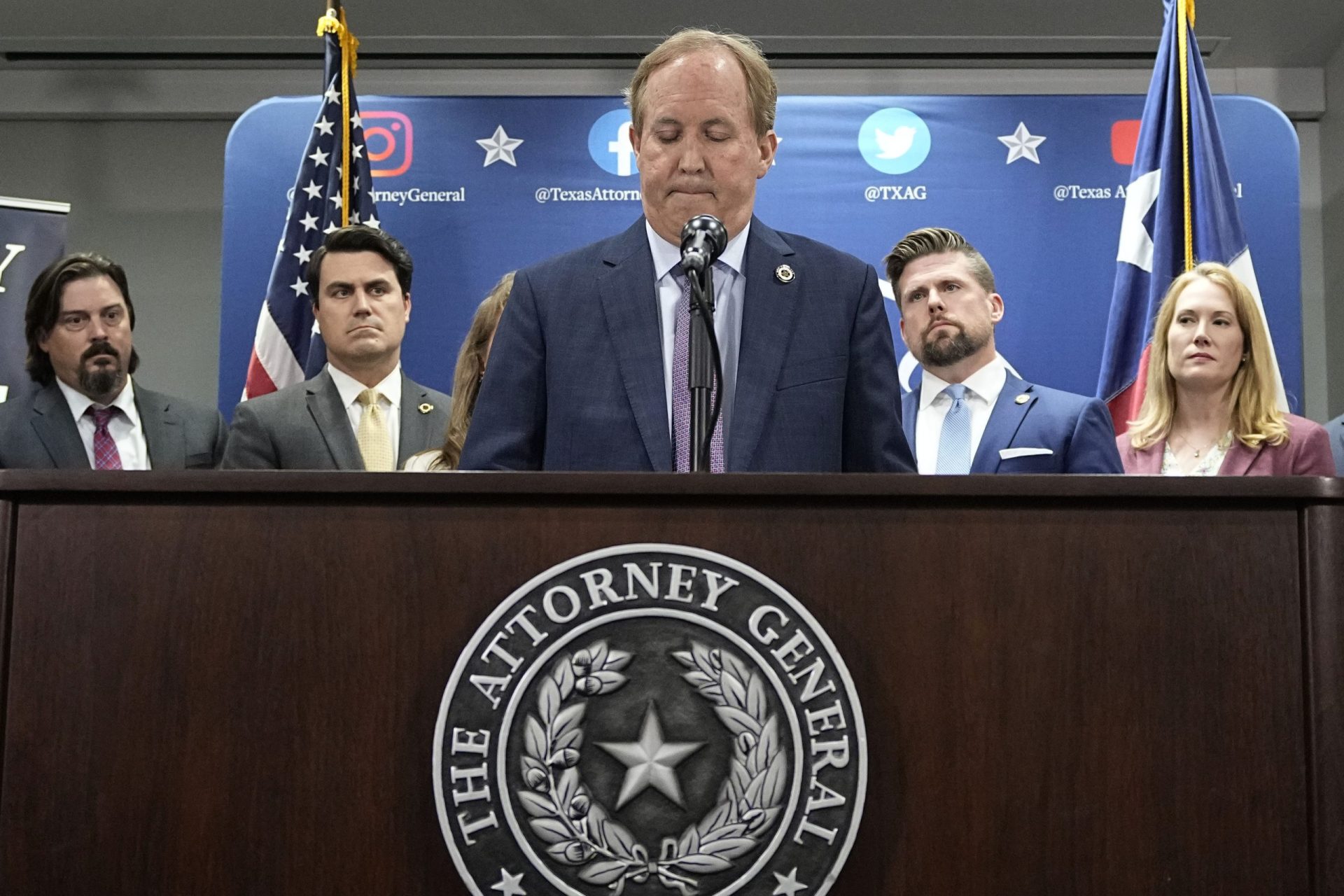

Paxton first publicly broached the settlement at the Capitol on Feb. 21, when the House appropriations committee held a meeting to discuss his agency’s budget. That day, Paxton talked about his agency’s wins. Lawmakers brought up the settlement.

In a video recording of the hearing, the committee members quizzed the attorney general about whether Texas taxpayers should be on the hook to fund the settlement.

Paxton deferred most questions to the deputy sitting beside him. Chief of General Litigation Chris Hilton defended the $3.3 million funding request, saying the state would save money by putting the already-costly whistleblower lawsuit to bed.

“General Paxton, would you be willing to pay for it out of your campaign account?” Rep. Jarvis Johnson, D-Houston, asked at one point.

Paxton did not answer. In the hearing video, Paxton motioned to Hilton to respond.

“I don’t want to speak for the attorney general,” Hilton answered, reiterating Paxton had admitted no fault in the settlement. “I’ll just say that there is no whistleblower case where any individual has paid anything because the individual is not liable under the terms of the statute.”

Paxton personally addressed the settlement before the hearing, however.

Appearing on Mark Davis’ conservative radio show the week before, the attorney general said his agency had to settle because Travis County, where the whistleblower lawsuit was filed, was too liberal a venue for him to get a fair shake.

If he thought the Austin-based judge would be impartial, he told Davis on Feb. 15, “then I would absolutely fight this to the bitter end, despite the cost.”

Paxton’s impeachment

By March 6, the messages between Leach and Smith devolved into veiled threats.

First, he accused her of begging him not to hold a public hearing on the settlement. She denied that, calling him a liar.

“Bring it, Michelle,” Leach texted, to which she responded, “Ok don’t ask me to.”

“I won’t be talked out of doing my job and fulfilling my oath,” he said.

“I stood in 100-degree weather to get you elected. Never forget that,” Smith replied. “You want to go against me go ahead.”

Leach tried once more to get Smith to commit Paxton to appearing before the Committee on the Judiciary and Civil Jurisprudence, which he chairs, to answer questions about the settlement.

“I will have a discussion with AG Paxton and get back to you,” she responded.

It was the last time the two texted about the settlement funding, according to the public records the agency released to The News.

As the legislative session progressed, some state lawmakers became more vocal about their concerns. Speaker Dade Phelan, R-Beaumont, publicly said funding the settlement was not a proper use of taxpayer money. When budget writers released their finalized proposals in mid-May, they didn’t set aside any funding for the settlement.

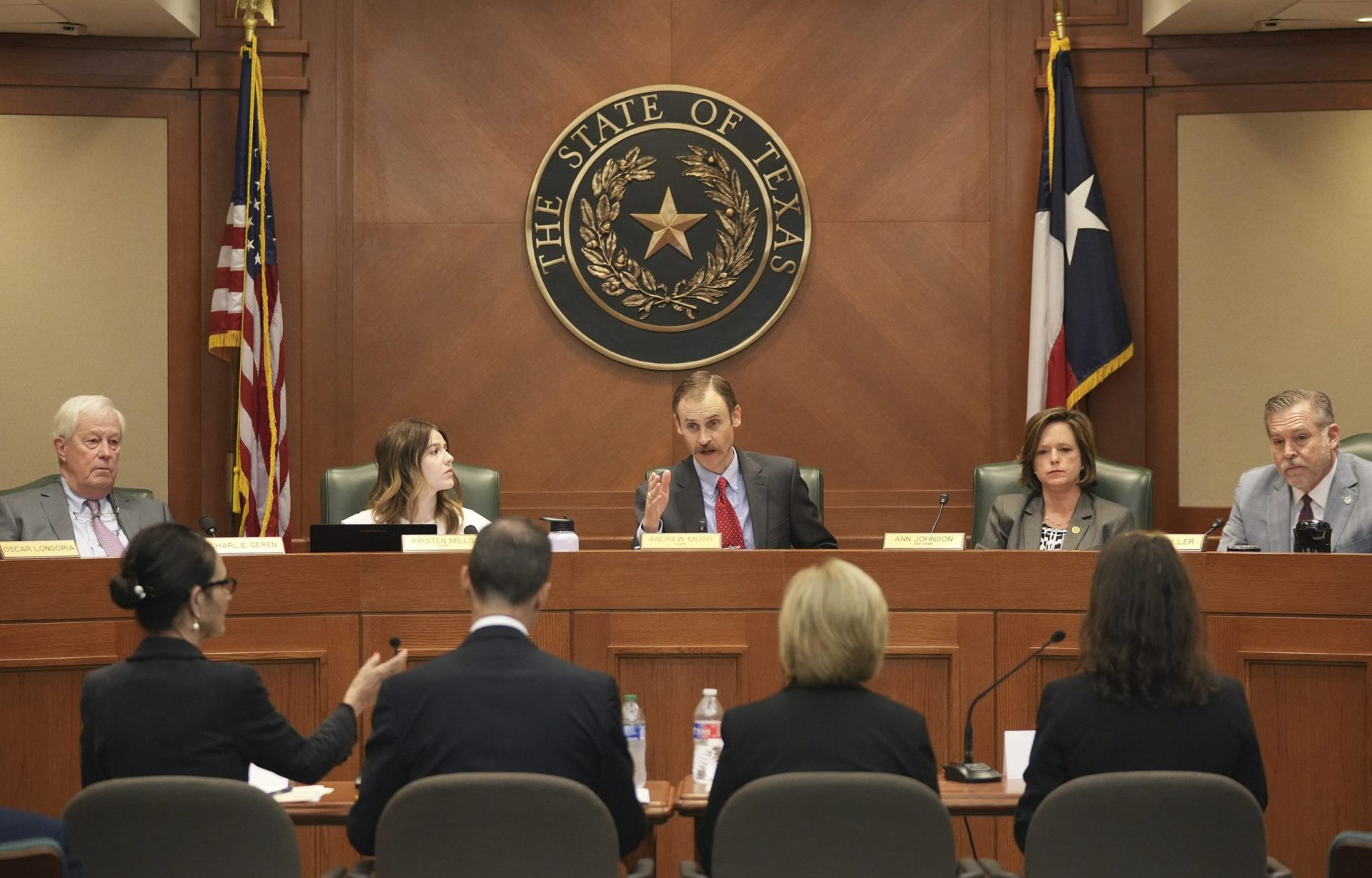

On May 23, the House Committee on General Investigating recommended Paxton be impeached.

The committee members said he’d erred in firing the whistleblowers and that the corruption allegations against Paxton had merit. The investigating panel lobbed a number of other accusations against the attorney general, including bribery, conspiracy and unfitness for office.

Hilton showed up to that meeting demanding to be heard.

“They have not reached out to our office at any time during their investigation,” Hilton told reporters outside the hearing room. “I’m here to testify.”

The attorney general himself was not there, however, and Hilton wouldn’t answer questions about his whereabouts.

Paxton’s trial

Since impeachment, Smith has continued to work against those attempting to oust Paxton from power.

A former member of the Rockwall City Council and director for the conservative organization Concerned Women for America, according to a 2016 Texas Monthly story, Smith works for both Paxton’s campaign and the agency he leads.

Amid his fight against securities fraud in 2017, she compared the attorney general’s legal troubles to the persecution of Jesus Christ, according to court filings. She recently garnered headlines in the Houston Chronicle for helping set up a private meeting between Paxton and a GOP activist who his agency was prosecuting for unpaid child support.

She has rallied allies in social media posts where she barely masks her rage against the lawmakers she described as the “RINOs” — Republicans in Name Only — who voted to impeach the attorney general.

“Ken Paxton deserves due process,” she wrote on Facebook on June 16. “Every state representative who went along with this sham, illegal impeachment, I hope Karma hits you hard.”

It’s unknown whether Smith passed along any of Leach’s text messages to the attorney general or when Paxton first learned that lawmakers were considering calling for his removal from office. Since he was impeached, Paxton and his lawyers have spoken out against the process, calling it a sham meant to oust a duly-elected attorney general.

His agency also tried to make inroads with lawmakers. Senators, who will serve as jurors in his trial, found packets of documents detailing Paxton’s defense on their desks the day after impeachment.

Before Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick instituted his gag order this month, Paxton’s lawyers repeatedly cast doubt on the evidence against their client and the process itself.

They have filed a motion arguing the attorney general can’t be forced to testify when he faces senators at his September trial.

Patrick has not made a decision regarding Paxton’s request.

“I have to keep this a fair trial. The defendant deserves a fair trial,” he told CBS News Texas on July 18.