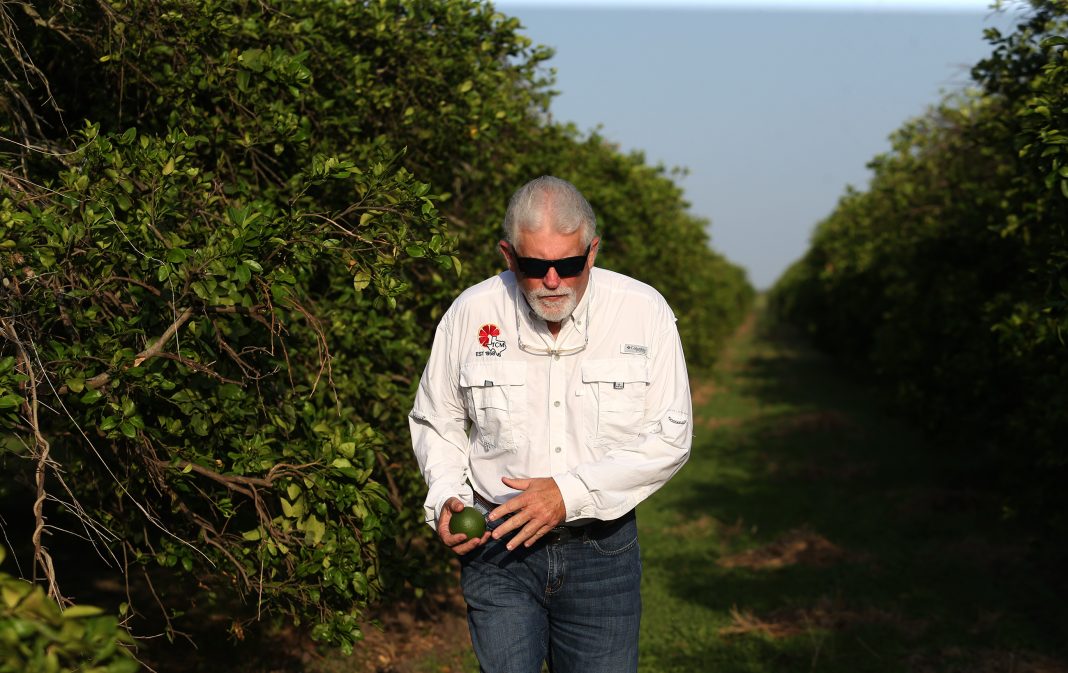

A bright green citrus the size of a baseball sat on the tailgate of Dale Murden’s truck parked alongside his Cameron County groves Thursday morning. “You see that fruit right there?” he asked. “It should be twice that size right now.”

Cloudless, pale blue skies promised no rain that day to the farmer who’s been looking up, relying on rainwater for more than 40 years.

“You anticipate drought. You just do,” Murden said. “Never had a season where I didn’t have any water.”

This year came close.

He’s only been able to water his fields once, in January, when he received his allocation from the watermaster. Normally, he would’ve irrigated six to seven times by now.

Then again, farmers lost their sense of “normal” three years ago.

Crops flooded with Hurricane Hanna at the start of the pandemic in 2020, froze the next year, and are now drying up through a drought that is forcing farmers to make hard choices.

“Who could’ve planned that? I mean, damn. I don’t know what’s next,” Murden said.

Between citrus and sugarcane, the other ubiquitously planted Valley crop, both grow across 25,000 acres of commercial industry in South Texas. The drought threatens a nearly billion dollar business and thousands of jobs.

“Without water, we’re out of business,” Murden said matter-of-factly.

Between the water wars with Mexico, the absence of rain and the subsequent declining levels at the Amistad and Falcon reservoirs, where South Texas gets its water supply, the Rio Grande Valley land is parched.

“We have not had an allocation in five months now,” Sonny Hinojosa, the general manager of Hidalgo County’s Irrigation District #2, said Friday.

Water irrigation districts stand between irrigators and the watermaster. Farmers have a sort of water bank account with the state, but they can only withdraw their allocations through the water irrigation district to which they belong.

“We will place that order through the watermaster, and he releases that water from storage: Amistad and Falcon,” Hinojosa explained. “He releases it, and then we pick it up through our pumping plant via canals and pipelines. And we’ll deliver it to the farmer.”

The state’s watermaster from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ, determines, however, how much water the irrigation district will manage for their region. That’s based on priority and deductions that happen at the end of every month, Hinojosa explained.

Hinojosa learned the intricacies of the process during his eight years at TCEQ’s watermaster office before working at the irrigation district where he’s been for nearly 28 years.

Cities, industrial and domestic users have priority over accounts held by irrigators and mining operators.

Acre-feet is the unit of measurement often used when discussing irrigation. It’s the volume of water that would cover one acre to a depth of one foot.

Each month, the watermaster will calculate the amount of usable water. Hinojosa said they first set aside the amount of water that sits below the dam outlets. Then, they deduct an amount for the reserve used by priority users: cities, industry and domestic. Irrigation and mining accounts are then considered.

An operational reserve of about 75,000 acre feet will be deducted, too. Though, Hinojosa said, that amount can fluctuate from 75,000 acre-feet to none.

The amount the districts receive reflects the year’s abundance or scarcity of water.

On a good year, like 2017, Hinojosa said the district received over a million acre-feet in allocation. Lean years, like in 2012, it only saw 218,000 acre-feet come its way.

On average, considering the last nine years, Hinojosa estimated the district receives about 680,000 acre-feet. This year, they’ve only received 27,000, and it’s likely to stay far below 2012 levels.

“It’s too soon to tell, but just from looking at weather events, it doesn’t appear we’re getting an allocation for the July period,” Hinojosa said.

Strategizing can help mitigate the effects of drought, but even those are drying up.

“Right now, our farm is just practically out of water,” Joe Metz, who owns nearly 1,100 acres of farms and pastures in Hidalgo County, said.

Although Metz is semi-retired and rents out most of his land to others planting crops or raising cattle, he worries about the availability of water.

The last time Metz can recall a similar crisis was 20 years ago, when he was still at the tiller planting sugarcane, a perennial crop that grows like grass year-round.

“We had two irrigation wells where we pump water from,” Metz said. “I bought other people’s allocation. I pumped water out of the drainage ditch, and there’s a drainage ditch across the river. It’s really salty type water. We pump that out and put it in with the good water just to have more water. We got through without ever running out of water.”

These days, no one has extra supply to sell.

“Everybody’s looking for water. All the places I used to buy water from, they don’t have any water,” he said.

Before 2020, farmers like Metz and Murden weren’t buying extra water to irrigate their fields on an ideal 20-day schedule between rain showers. It’s not possible to stay on that schedule during droughts.

“If I didn’t buy it last year, I would’ve had no way to find any for this year,” Murden said.

Bought water, referred to as contract water, isn’t safe from being allocated for other purposes though. In extreme cases of scarcity the state can claim that — its an unprecedented move being considered.

“What we’re approaching is that we’re going to have to debit waters from those agriculture accounts,” an assistant state conservationist from USDA’s National Resource Conservation Science in Texas said July 27. It followed a meeting between stakeholders and federal and state representatives from agencies like the International Boundary and Water Commission and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Debiting” an account is a negative allocation.

“In the history of the watermaster program, there’s never been a negative allocation,” Hinojosa said. One of TCEQ’s commissioners, Bobby Janecka, confirmed it has never happened, but he believes it could occur this year.

“We’ve been giving users, agriculture users less water in their account every month. We now may actually start decreasing any water bank accounts that they still have left. They may find that they’re losing water,” Janecka said.

Although it’s too soon to tell, Hinojosa pointed out a warning sign.

In June, the state dipped into the 75,000 acre-feet operational reserve. The amount it took represents more than it has taken in recent memory.

“They did dip into it — 54,500 acre feet, which is probably the largest loss that we’ve experienced in quite some time, if not ever,” Hinojosa said.

Farmers could resort to other strategies like changing from a flooding system where water pools in dredges between trees to a drip-system that uses micro-sprinklers and conserves water.

They can also decrease the ground they water. Last month, Murden bulldozed about 20 acres worth of older trees to reduce the amount he needed to irrigate from 80 to 60 acres.

Certain fields can remain fallow, or non-productive, for the year. It’s harder to do that with citrus, Murden pointed out.

“Can we keep the trees alive or do we even want to keep the trees alive? I’m here to grow fruit, not trees,” Murden said.

Citrus output during the freeze was about 25% of its average. This year, growers were hoping to go up to 60% or 70% and reclaim the number one spot they lost as the state that produces the most grapefruit.

Now, Murden’s watching his fields closely and taking it a day at a time.

“We’re going to start harvesting in October. This grove, we probably won’t even think about harvesting this grove until January or February. It’s too small,” he said.

After the freeze, shoppers picking grapefruit at the grocery store were not seeing the product from local producers.

“I said, ‘alright. We’re not on the shelf this year, but when we’re back please remember us. And you loved that sweet Texas grapefruit,” Murden said.

It’s a message that may bear repeating next year.

RELATED READING:

Hitting a low point: Drought, treaty noncompliance continue to stress RGV water supply