|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

EDINBURG — Dolia Gonzalez lives alone in a modest house located just a few blocks away from the street bearing her late son’s name.

Sitting by herself on her sofa wearing a light blue shirt that reads “USMC Mom,” the 93-year-old woman gazes at a pair of 8×12 photographs of her boy, her Freddy, clad in his jungle fatigues with the Vietnamese countryside behind him. This is the first time she’s seen the photos.

“Beautiful,” she said, staring down at her hands and gently holding the photographs. “I loved him so much.”

Freddy’s presence is felt throughout the old house, despite the fact that he never had the opportunity to live there. The house was built in 1969, but Freddy was killed in Hue, Vietnam in 1968.

He died Feb. 4 protecting the men in his platoon, an act of heroism that earned him a posthumous Medal of Honor and the subsequent naming of the USS Gonzalez, a destroyer in the U.S. Navy.

“I’ve been through hell and back ever since I lost my boy,” Dolia said.

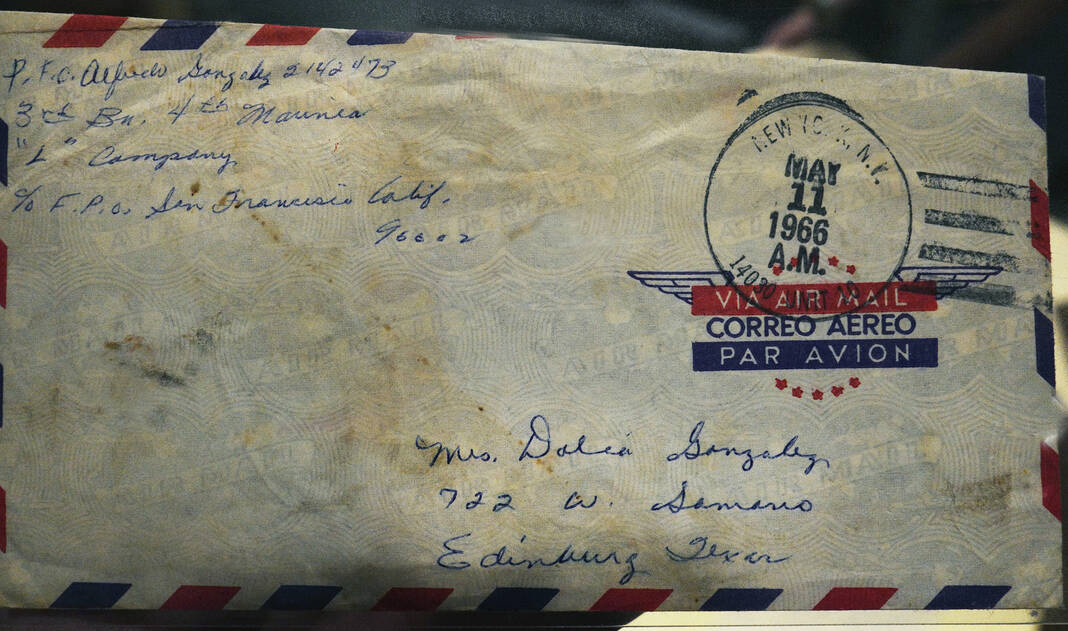

For 54 years, the mother of the beloved soldier, her only child, has held on to his memory by preserving letters he sent to her during his time serving as a sergeant in the Marine Corps.

“He was a good writer,” Dolia said. “I think in the letters — the way he wrote my letters, he was trying to tell me goodbye. It didn’t click with me. It was very hard because I didn’t know about his death until almost 12 days after he died.

“I felt like… why? Why me?” Dolia said, her voice cracking as she recalled the emotions she felt when she learned about her son’s death.

Dolia kept nearly 150 letters from her son, letters that now reside in the archives of the Museum of South Texas History. The loose-leaf correspondence written on wide-ruled paper offers a first-person glimpse into the mind of a war hero, but even more so, they show the strong bond and love between a son and mother.

“(The letters) mean a lot,” Dolia said. “I always kept them in a little box. As I read the letters, I would put them in a little box. … He wrote to me, my mom, my sisters, my friend.”

The letters depict a young man who ardently cared for his mother in the midst of his own dangerous situation. He would often send checks and money to his mother, and always reminded her to write back.

Another letter, dated May 8, 1966, includes a cover letter that reads, “Dear Mom, Here’s wishing you a Happy Mother’s Day.”

This year will mark Dolia’s 54th Mother’s Day without her son. Since then, she’s become the adoptive mother to Freddy’s fellow Marines who served with him in Vietnam.

“They all call me ‘Mom,” she said.

Pete Vela, a childhood friend of Freddy, described his old friend as tough and humble. He recalled this week the close relationship between Freddy and his mother, a closeness that he got to witness firsthand.

“She was always constantly trying to take care of him, as a good mother would,” Vela said. “He was very respectful to his mom. He didn’t have a father growing up. He did whatever he could to help his mom have bills paid.”

His mother recalled sending Freddy care packages filled with pan dulce and tortillas. In one particular letter, he asked his mother to send him some records.

“Mom, buy me two albums,” the letter, dated Jan. 13, 1968, read. “One by Carlos Guzman ‘Tiempo De Llorar,’ y Noe Pro ‘La voz (voice) international de Noe Pro.’”

In what is believed to be his last letter to Dolia, Freddy is brief, yet looking forward to getting some time away from Vietnam.

“Hi Mom, A short letter to let you know that I am just fine,” the letter dated Jan. 26, 1968, read. “I am going on R&R the 29th of Feb. to Hong Kong. Me and Sam Reyna are going together. Am also sending a couple of pictures.

“Well Mom, guess this will be all for now,” the letter continued. “Bye for now. Write soon. Send another package. The Mexican candy was real good — Mom. Love your son, Fred.”

According to Museum of South Texas History Chief Executive Officer Francisco Guajardo, Dolia attempted to donate the correspondence to the museum multiple times, but it was too difficult for her to part with the letters until the summer of 2020.

“I think that the letters that Freddy sent have been, for half-a-century, Dolia’s source of inspiration and motivation in life,” Guajardo said. “It is Freddy’s letters, Freddy’s words that have given her strength to be. The greatest gift from Freddy were his words, posthumously.”

The museum is currently working to prepare an exhibit of his letters for Memorial Day.

“Our position is that this is for the world,” Guajardo said. “Freddy really was taken from Dolia and given to the world. I think that’s how she understands it, so she has toggled back and forth between, ‘He’s mine,’ and ‘He’s of the world.’ It’s given her sustenance.”