McALLEN — Troopers with the Texas Department of Public Safety were instructed Wednesday to stop, even impound, civilian vehicles used to transport migrants via a ‘vague’ executive order that stakeholders — including attorneys, congressmen, city leaders, nongovernmental organizations, and even commercial entities — do not yet know how to interpret or how it will be enforced.

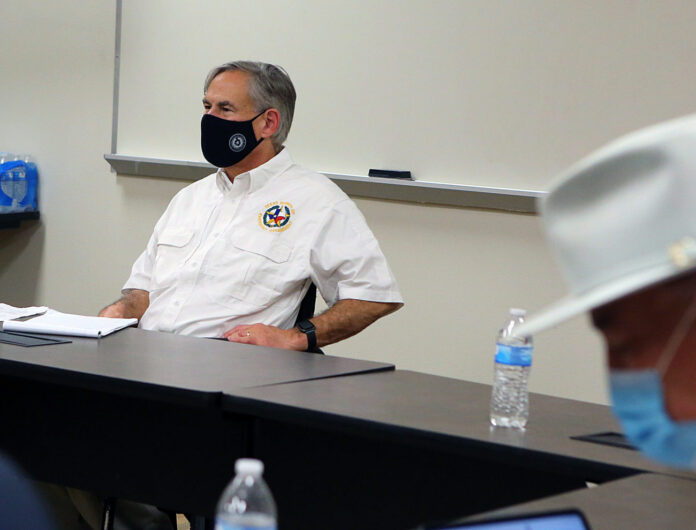

Gov. Greg Abbott’s order gives DPS the authority to restrict the ground transportation of migrants who have crossed illegally into the country or those who would have been subject to expulsion under the federal public health code known as Title 42 by anyone other than federal, state or local law enforcement officials.

Under his orders, troopers would be able to reroute the driver to their point of origin, like a shelter or a port of entry, and have the ability to impound the vehicle.

“We’re going to start getting into legal issues that are going to be hard to enforce, and how do you do that,” McAllen Mayor Javier Villalobos asked Wednesday. “I understand the sentiment. I understand the intent. I just don’t see how we’re going to do it.”

Abbott’s intention was to address public health concerns raised in La Joya Monday, when a local citizen called the police department after seeing a migrant family who appeared to be sick with COVID-19 at a local restaurant without facial coverings. Upon further inquiry, the family told the officers they were quarantined at a nearby hotel after testing positive for COVID-19 and being released by CBP.

La Joya Mayor Isidro Casanova received a call from Abbott on Tuesday after a press conference there. By Wednesday afternoon, Abbott had already signed the executive order.

The order will not directly affect local law enforcement officers or federal employees with CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement who drive migrants through the local community.

Civil rights attorneys, however, called the order vague, unconstitutional and a precursor to racial profiling.

Kate Huddleston, an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Texas, said the order attempts to address a federal issue.

Under the order, migrants who entered the country illegally or who were subject to Title 42 expulsions are not allowed to receive civilian transport. It’s a categorization that Huddleston believes is difficult to interpret legally.

“That would mean that state law enforcement officials are charged with categorizing people under federal immigration law and restricting their movements in the state of Texas based … under these categories that Abbott has set in the executive order,” Huddleston said. “This is really not the role of the state in our federal system.”

The complexities may not matter if DPS troopers know where to look for their suspected targets, like buses and vans leaving the Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley Respite Center in McAllen, Villalobos said.

“If you’re just going to be just lying in wait on buses, that’s different,” the mayor said. “But, what they’re talking about is that anybody other than a government employee can’t do it.”

Other volunteers, like Felicia Samponaro-Rangel with the Sidewalk School who drives migrants from the port of entry to the Valley, may be affected. She helps a small group of people that the Department of Homeland Security exempts from Title 42 expulsions under a consortium process known as Huisha. The process is not well-known — a fact that doesn’t escape Samponaro-Rangel’s notice.

“You read the declaration, it’s so muddy,” Samponaro-Rangel said. “Combine that with the fact that if an officer does stop us, he’s not going to know what a Huisha case is and what a consortium is. We’re not going to have a discussion about the legalities of what’s happening in my car. He’s probably just going to see a migrant and impound my car, whether they’re legally here or not.”

Abbott’s order will mainly impact shelters like the respite center where volunteers drive migrants from the center to other overflow facilities, quarantine hotels, bus stations or airports.

“It’s going to cause chaos down there,” U.S. Representative Henry Cuellar said about the impact Abbott’s order is going to have on the respite center.

As of Wednesday, the executive director of the charity, Sister Norma Pimentel, said the shelter was no longer at capacity, like it was on Monday. But she declined to comment further on the effect of the governor’s order.

Cuellar, who read the governor’s order, believes it will impact migrants’ mobility at the respite center, which sits across from the McAllen bus station where Greyhound operates buses that transport migrants across the country.

“I assume, if you’re Greyhound or somebody that’s transporting people from the respite center on behalf of Sister Norma, (they’re) going to be prohibited from doing that,” the congressman said.

Greyhound declined to comment on the issue Wednesday afternoon.

“Greyhound is currently reviewing Governor Abbott’s newly released executive order and has no further comment at this time,” the one-sentence statement from the company said.

Still, the bus service was busy moving migrants from one place to another Wednesday evening, hours after the governor issued his orders.

Evelin, a 27-year-old Guatemalan mother, sat close to the McAllen bus station door with her 3-year old daughter by her side. The pair entered the U.S. a few days ago. They spent two nights sleeping on the ground under the Anzalduas International Bridge without a blanket and surrounded by mosquitoes. CBP set up a temporary outdoor processing site there in late January to help with the limited processing space throughout the Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol sector.

Over the last couple of months, the agency began to struggle to find space for the thousands of migrants who cross every day through the area.

On Tuesday, Border Patrol said it encountered over 800 people in a 24-hour time span. One group of over 500 migrants was the largest agents have processed to date this year.

Human resources are running so low, Border Patrol officials considered closing down certain checkpoints and moving staff off enforcement duties to processing duties, a move that has yet to be approved, Cuellar said Wednesday. Other logistics, like transportation, pose another challenge.

Brian Hastings, Chief Patrol Agent in the Rio Grande Valley, asked Hidalgo County Sheriff Eddie Guerra this week to borrow vans and buses the county isn’t using at the moment to help move migrants after the contractor failed to keep up, Guerra said Wednesday.

Yet thousands, like Evelin and her daughter, continue to filter in. Shelter space is equally hard to find.

After Border Patrol released the mother and daughter to the respite center on Tuesday, the pair tested negative for COVID-19 but were denied an overnight stay at the shelter, Evelin said.

Instead, they were told to find a hotel nearby. They showed up to the bus station and were ready to board as the 3-year old cried for milk. Evelin opened a plastic bag, filled a bottle with water and milk formula, stirred it and gave it to her daughter.

She agreed with the governor.

Migrants who are sick should be quarantined. But after they recover, she said she hopes they will have a chance to move on.

“They should give us the opportunity,” Evelin said. “Everybody is at risk.”

She glanced over at her daughter, who was happier after receiving the bottle. Evelin urged her to put her mask on. The bus was coming in less than an hour.