It took a video clip just over a minute long to make Fred Gracia famous.

The clip shows Gracia, a referee, ejecting an Edinburg High defensive lineman from a home game last December.

The other team claps. Some of the fans cheer. Gracia, 57, stoops down to pick up his flag and starts walking back toward the middle of the field.

Then, offscreen, lineman Emmanuel Duron charges onto the field. You hear people shrieking before you see him barrel into the frame.

Gracia notices something’s wrong just a moment before he goes airborne, bracing himself. Then Duran rams into him, hard, on Gracia’s right side. Both feet go off the ground for just an instant and then the referee slams down onto his back, both legs stuck up woodenly in the air.

Duron is restrained by a couple of his teammates and led off the field.

The crowd gasped when Gracia got hit. That shock turned to anger in a few moments, the audience hurling down cusses.

That’s how America reacted too, as the clip and the aftermath of the attack were broadcast and written about nationally in the days after the attack.

Horror followed by disgust.

That, Fred Gracia says in his first interview since the attack, should not — cannot — be the end of the story.

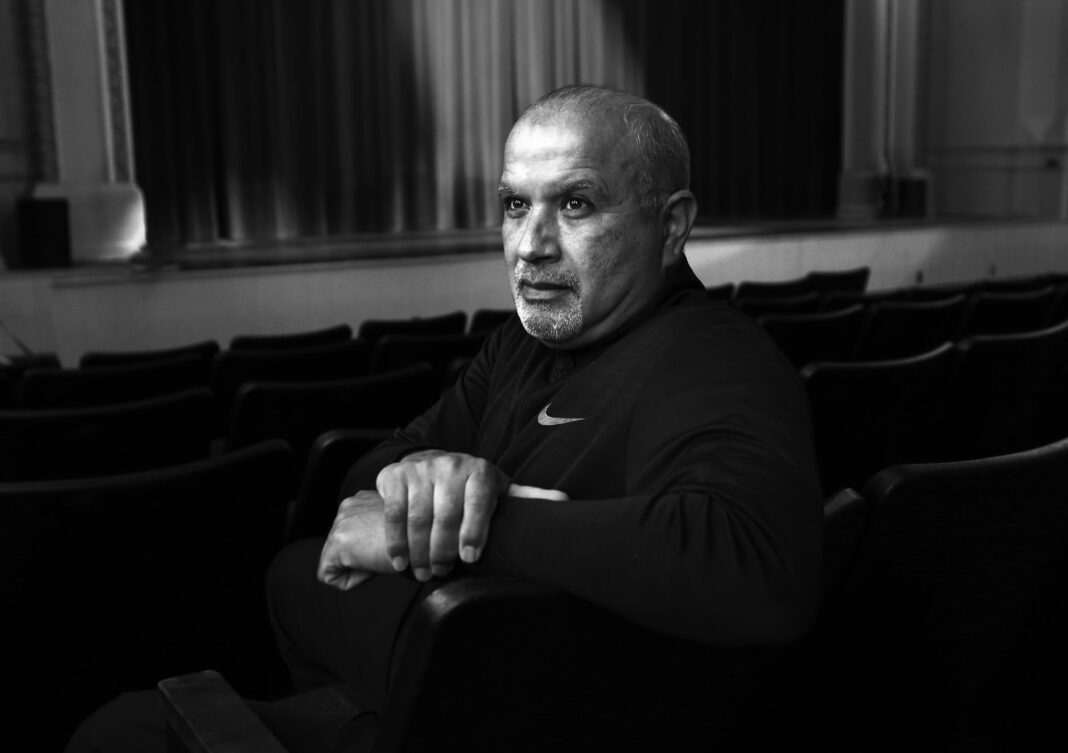

THE REFEREE

Fred Gracia grew up in the housing projects in Mercedes, practically in the shadow of the football stadium.

It wasn’t a particularly easy childhood. Gracia’s father died when he was 7, and his mother raised him and five other kids.

What Gracia did have was sports. He could hear coaches blow the whistle from his house when spring training started, and he would run out to the stadium, to help drag practice dummies out of the fieldhouse and do what he could to help the team. Then he’d sit there and watch practice, practically all day long.

“Sports was what became my passion,” he said. “I was always out there playing ball when I was a kid. Doing my own thing and staying out of trouble.”

Gracia played ball and kept watching afterwards, sitting in those stands in Mercedes. He realized he usually had his own opinion on the calls the refs were making, and figured he’d give it a shot.

That was 30 years ago. Being a referee has become part of his identity. Gracia loves the passion he’s seen on the field in hundreds of games — it reminds him of when he was an athlete too. He likes, especially, enforcing the rules. Values come from those rules; no one’s above the game.

“Mainly respecting the opponent and respecting the game,” Gracia said.

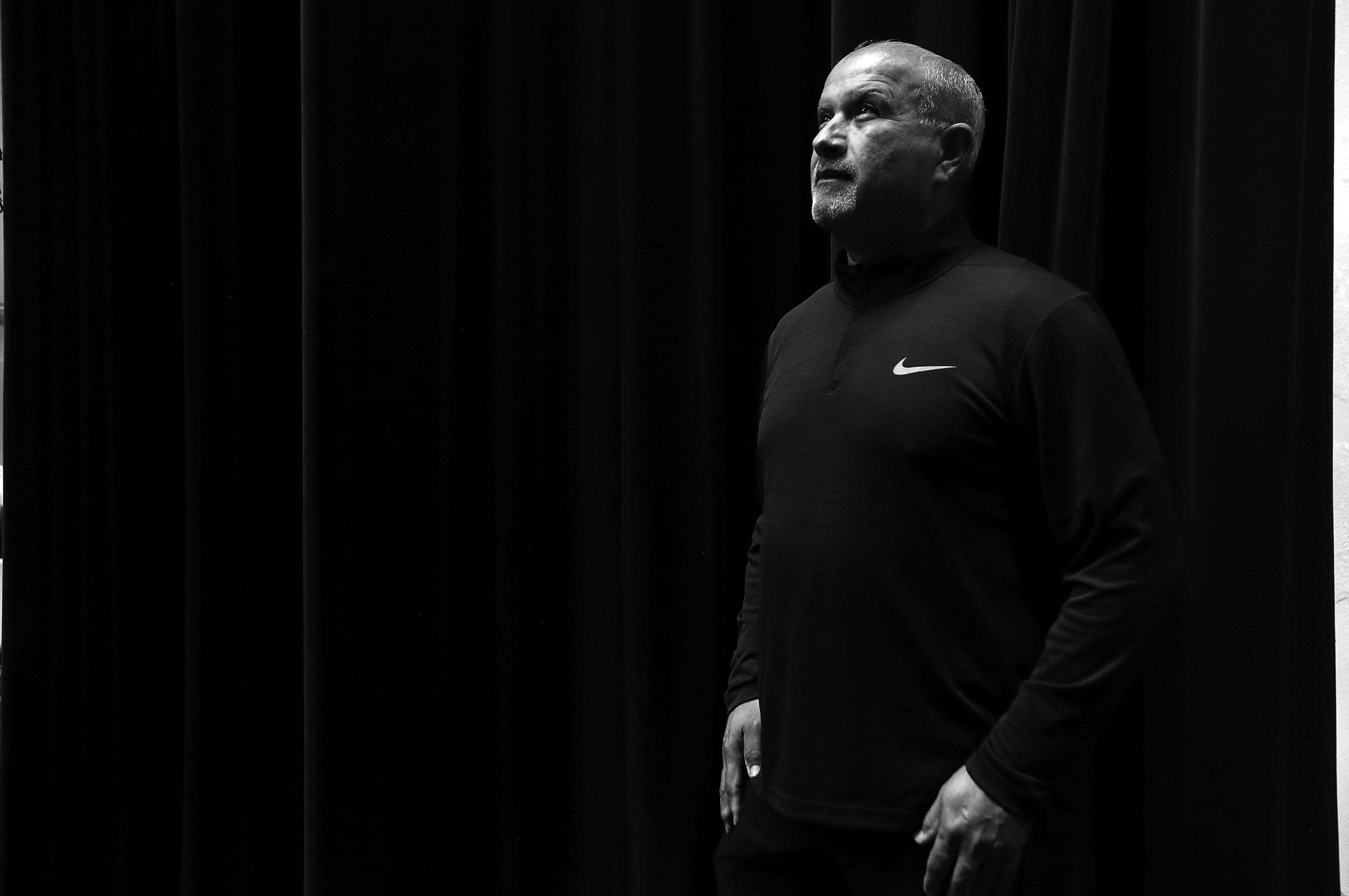

Dec. 4, 2020, wasn’t much different than any of the other.

Gracia remembers warning Duron about how he tackled the PSJA quarterback in the first quarter. About halfway through the second quarter, Edinburg was ahead of PSJA High by a touchdown. The game was getting heated and Duron began raking in flags, and eventually another referee made the decision to eject him from the game.

Gracia just made that news public.

“And all the sudden I just get blindsided,” Gracia said. “That’s all. It’s all I remember.”

Gracia couldn’t see who hit him, but his gut told him who it was. He says he forgave the 18-year-old there on the field, and wished him well.

“For me, for me to be able to move on I have to be a forgiving person,” Gracia said. “And by forgiving I’m able to move on. And I hope he makes peace with himself.”

THE AFTERMATH

People huddled around Gracia after he went down. Eventually he was able to get up and walk off the field to cheers from the crowd.

Medics evaluated Gracia for a shoulder injury in an ambulance outside the stadium. He and his attorney declined to discuss any injuries he may have sustained or still have.

Calls and texts started rolling in not long after the attack, friends and family and other officials offering a word of compassion or telling the referee he was in their prayers.

“I was deeply, deeply humbled,” he said. “It was an emotional roller coaster.”

Gracia’s not off that roller coaster yet. Not a day goes by without someone asking him if he’s that ref who got slammed.

Sometimes Gracia lies and says no. He wants to move on, and the incident haunts him. Other times he’ll open up a bit.

“They all want to know what’s going on with him, and I really don’t know,” Gracia said. “I just tell them to pray for the young man.”

That small scale fame has changed Gracia’s identity. He didn’t umpire girls fastpitch this season. The crew of referees he was chief of split up. Gracia doesn’t know if he’ll go back on the field next year.

“I’d love to and I’m thinking that I will, but sometimes — the drive for that has kind of left me,” he said. “And I don’t want to go out there, being asked questions, and the focus being on me.”

There’s also a very physical fear Gracia just can’t shake. Being a referee, he said, has always been like being in a bubble. People may yell and cuss and shout, but ultimately they can’t touch you.

The attack in December shattered that illusion.

“Sometimes I don’t know how I’m going to react if somebody charges at me and wants to confront me about a rule, whether it be a coach or somebody, so for right now I just stay out,” Gracia said.

While Gracia was still laying on the turf Duron was being escorted off the field. He was later arrested and charged with class A assault.

Duron’s attorney’s did not respond to a request for comment Thursday. The former linebacker did address the incident in a video apology released later in December.

“I know much has been said about me, and I would like to say a few words today,” Duron said. “To Mr. Fred Gracia, I would like to apologize to you personally. I hope you’re doing well. I am extremely sorry for my actions towards you, and I hope one day you can accept my apology.”

That apology didn’t change the fact that Duron’s decision in December ended his high school career as an athlete and brought intense, negative attention to Edinburg High.

“It was a dark cloud over our district for a couple of months, and we took it very, very seriously,” current Edinburg CISD Superintendent Mario Salinas said Wednesday.

Salinas was an assistant superintendent when Duron tackled Gracia back in December. He remembers being pulled out of a special board meeting and told he needed to get to the stadium. He didn’t realize the severity of the situation until he got there.

“I mean, I’ve been watching football games for more than 50 years and I’ve never seen anything like it,” he said. “And to see it happen in my hometown, it was just shocking.”

Salinas said the district took disciplinary action within their program in the wake of the incident, and opted to forfeit Edinburg High’s playoff spot.

The UIL took action of its own, suspending Duron from all UIL-sanctioned activities for the rest of his senior year and placing head football coach JJ Leija on a one-year probation.

“It happened,” he said. “The young man was disciplined as per our policies, and as you can imagine we don’t condone that kind of behavior. Not here, not anywhere.”

Salinas said he understands Duron got a football scholarship to play football at a small college in Georgia. Salinas, like Gracia, hopes the teen grows from the decision he made that December evening.

“Hopefully he will take this incident that happened and learn from it. And not only him — other athletes that participate in sports,” he said.

THE FUTURE

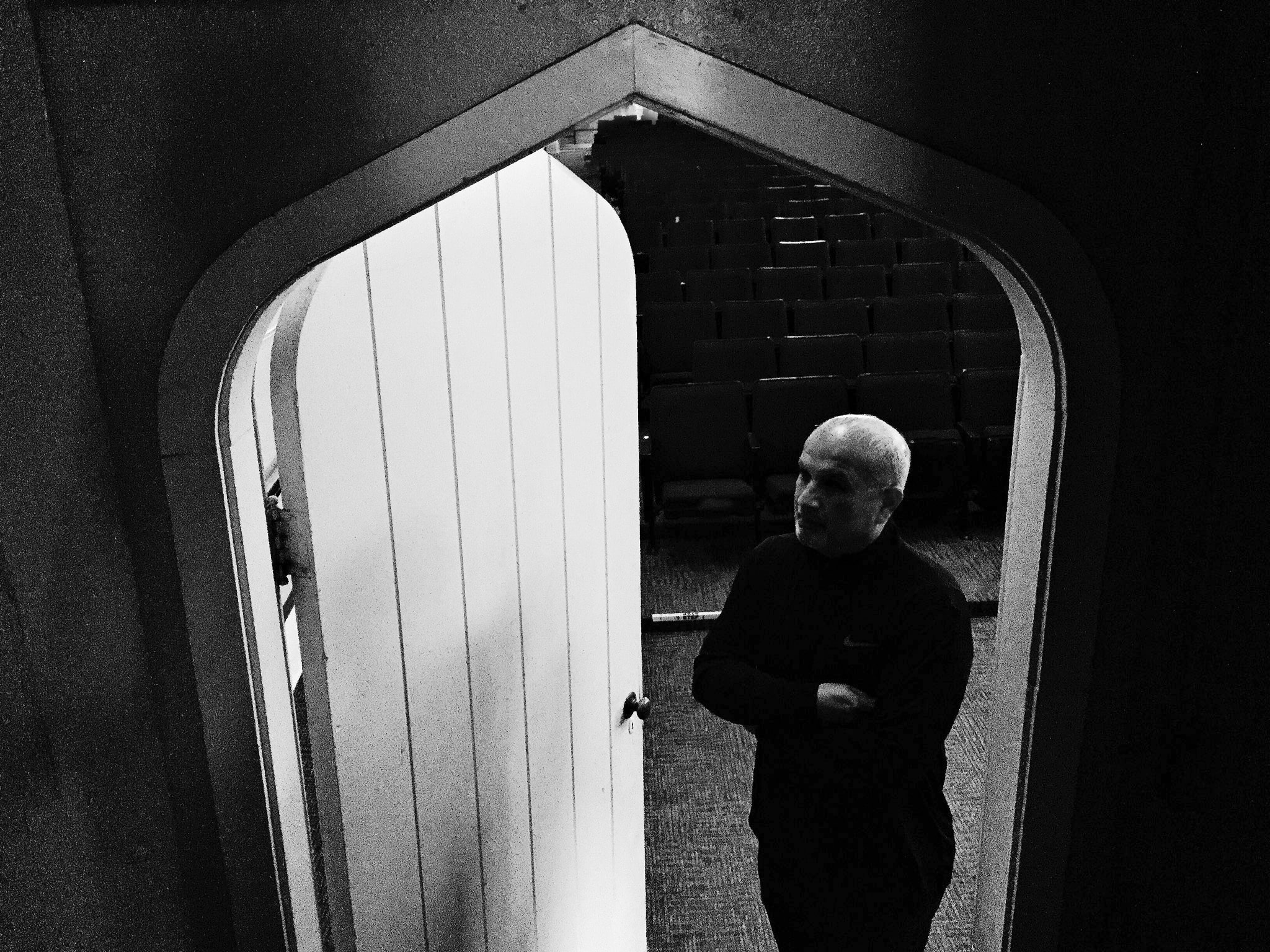

The question, for Gracia and his attorney, is to recreate that bubble of invulnerability that surrounded him on the field up to the point Duron slammed into him. How to make refs safe.

At Edinburg CISD that boiled down, for the most part, to a heap of new protocols and required training. High schools came up with plans and protocols for athletes. Student athletes are required to sign behavioral contracts that outline etiquette. The district subscribed to a curriculum called “2 Words.”

“What it is, it’s staff development for coaches to teach sportsmanship and character in athletes,” Salinas said. “It’s lessons for students, lessons for coaches, lessons for parents. So we took that on as an ongoing staff development for all our coaches, middle school and high school.”

The incident also highlighted the need to address mental health issues and emotional problems in the district’s student body, a conversation Salinas said was already happening.

“One of the things that we’re going to emphasize, because of the pandemic but just in general with teenagers and students, we’re going to emphasize the social and emotional aspect of our mission,” he said. “It’s not just reading, writing and learning how to do math; it’s becoming evident that social/emotional learning is important as part of our mission, because kids are kids and they go through all types of trauma.”

Mental health and how it’s treated in schools is a tentpole issue for Gracia and his attorney, Richard Hinojosa with Hinojosa Law in Houston.

“We think that there are underlying mental health problems in high school sports, in sports in general that have gone unchecked for a long time,” Hinojosa said.

Gracia and Hinojosa said they’ve been working with Rio Grande Valley psychologists about mental health screenings. They think districts could come up with some kind of form a student or parent could fill out that would screen athletes for mental illnesses earlier in their life. They think training coaches to detect mental health issues could help do that as well.

“Not to call them out, but to maybe get some treatment for them earlier in case it is happening in junior high, their sophomore year, whatever,” Hinojosa said.

It’s a hairy issue. Stigmas around mental health and the threat it could pose to a student’s athletic participation make implementing some kind of screening controversial, Hinojosa said. Still, he and Gracia say it’s a conversation that needs to be had.

“Honestly, I think this school district has an opportunity to be at the forefront of changing how we handle mental health problems in football and in sports,” Hinojosa said.

There’s some hope for that: Salinas said he feels the district might consider some sort of mental health screening.

Gracia and Hinojosa have found faster success on the statewide level. Last month Gracia testified in Austin to the Texas House of Representatives Committee on Public Education on comprehensive legislation that would prohibit a student from participating in future extracurricular activities for certain conduct involving the assault of an extracurricular activity official.

State Rep. Eddie Lucio III, who introduced the bill, likened it to a line in the sand. Lucio’s father, state Sen. Eddie Lucio Jr., introduced similar legislation there earlier this year, saying it too was prompted by Gracia’s assault.

Gracia said he thinks that legislation is the kind of response he was hoping for. At the end of the day, he says he wants to go back to the game and the stripes and the Friday night lights. He just needs to know he won’t be assaulted for doing his job.

“All I want is to have change,” he said. “This was not a hit on just me; it was a hit on all officials. When one of us goes down, we all hurt. And nothing better can come out of here than change. That’s all I want.”