BY NORMAN ROZEFF

Upon the start of the Civil War scant Union forces stationed in the Valley soon were confronted by a overwhelming Confederate army that would allow them to evacuate the area.

The Steamer Daniel Webster with Maj. Fitz-John Porter, Assistant Adjutant General U. S. Army and part of General Winfield Scott’s staff, departed New York on 2/15/61 and arrived at Brazos de Santiago on March 3 to commence evacuating Federal troops.

Porter was assisted by Captain George Stoneman of the 2nd Cavalry and Commissioner Nichols. Transported to New York were Companies M, Second Artillery, and Companies C and E of the 3rd Infantry. By March 21 the last U.S. officers had departed.

One historian noted that Captain Stoneman “ ‘upon a touching appeal from Colonel Ford’ left behind his company’s weapons for use of civilians against possible Indian attack.” Stoneman and Ford were friendly as they had together fought Indians along the wild frontier of the state.

Almost immediately with their departure the Confederates took control of the garrisons. They were not to remain there however as the Brazos Island position would be poorly defensible against possible Union warship bombardments.

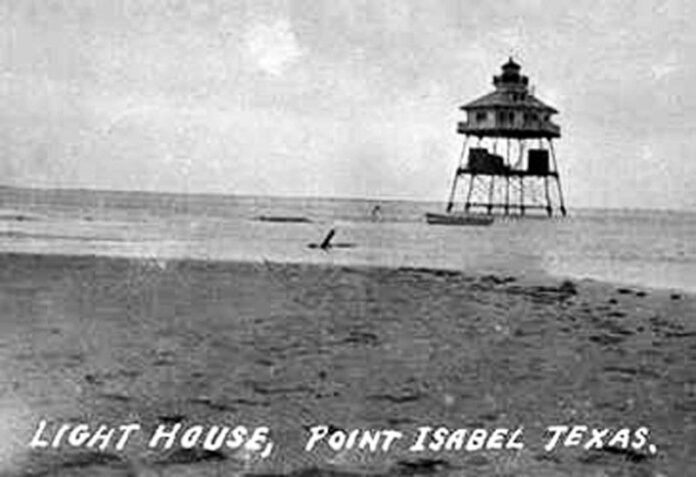

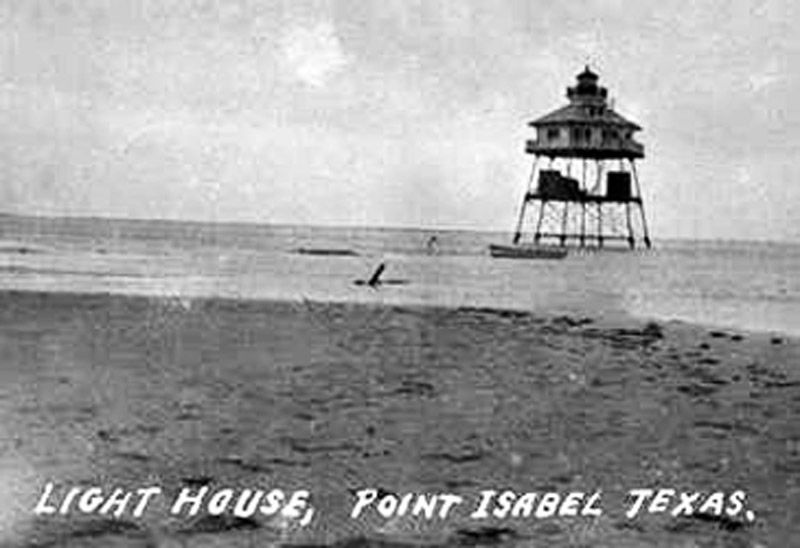

As noted above, on 2/21/61 Texas Confederate States of America (CSA) troops under Col. John Ford had captured the U.S. Depot with its mortars, siege guns, and ordnance in the town of Brazos de Santiago on the north end of Brazos Island. General John P. MaGruder of the CSA ordered the blasting of the Point Isabel Lighthouse, but, when executed, it was only damaged. Later its light equipment was removed and buried in the backyard of Ford’s Brownsville residence.

On April 19, 1861, seven days after the war had begun, President Abraham Lincoln gave an order to blockade all rebel seaports, including that of Brazos de Santiago (transl.: Arms of St. James. Originally the name of the settlement was Brazos de St. Iago. After shortening to Brazos St. Iago, it was corrupted to Brazos Santiago. ) on Brazos Island. Despite its strategic location the port left a lot to be desired. Expanded by the Mexican War, it had grown as a logistics center for military supplies in the years 1845 to 1848. Quotes from soldiers later stationed there were derogatory.

One Indiana soldier wrote that in his “whole recollection of Brazos St. Iago not one single pleasant incident” could be remembered. Recent West Point graduate, Lt. George B. McClellan, who would later be a failed Union general in the Civil War and run as the “peace” candidate opposing Lincoln’s second term, described the area.

He wrote “Brazos is probably the very worst port that could be found on the whole American coast…. nothing more than a sand bar, perfectly barren, utterly destitute of any sign of vegetation.” As Baughman commented in his book Charles Morgan, “The passage of the shallow bar was unusually dangerous in any sea, and often steamers ran aground, to remain for hours awaiting a higher tide.” He goes on to quote John W. Audubon who traversed the area on his way to the 1849 California gold fields. Audubon wrote “not a landmark more than ten feet high”, only “miles of breakers, combing and dashing on the glaring beach” littered with “dark weather-stained wrecks.”

When the Civil War commenced Union General Winfield Scott proposed a blockage of Confederate seaports coupled with a strategy to severe the Confederacy in two by controlling the Mississippi River. He hoped to squeeze the Confederacy materially and economically.

After J. B. Elliot of Cincinnati published an 1861 cartoon showing a snake stretched along the coast from Maryland to Texas and then north along the Texas western border all the way to Kansas, the scheme was named the Anaconda Plan by the press.

The blockade of Southern Ports, termed the Anaconda Plan or Scott’s Great Snake, had worked well with one major exception — on the Rio Grande separating Texas from Mexico. Because the river, years before, had been declared an international waterway, southern cotton once placed aboard steamboats on the river, or ferried temporarily on to Mexican soil, could proceed uninhibited to be placed on vessels bound for British and French ports, and even for New York City.

The end of November 1863 was to see the greatest event that would ever occur on Brazos Island. The Union military had decided to invade south Texas in order to interdict the lucrative cotton trade that was occurring there. This trade via Mexico was providing important funds for the Confederacy. A plan was put forward to stop the cotton trafficking south and the movement of foreign supplies north. It called for the formation of the Rio Grande Expeditionary force and the invasion of South Texas under the Massachusetts politician turned general, the inept military strategist, Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks.

A force of just under 7,000 Union soldiers was assembled in southern Louisiana. It included the 13th and 15th Maine along with units from Iowa, Wisconsin, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, the First Texas Cavalry (US), and the Corp d’Afrique, who were Black soldiers organized in New Orleans.

The landlubberly army troops were to experience a defining period in their lives. The voyage to South Texas and what ensued left an indelible imprint on their collective memories. What they were to encounter at sea was an intense, deep, low-pressure system accompanying the passage of a continental cold front, now locally termed a “Blue norther.”

The twenty-three transport ships had commenced their voyage from Louisiana in two parallel columns spaced one-half mile apart.

After boarding, the fleet, consisting of steamships, schooners, launches, tugs, and three gunboats including the sloop of war, USS Monongahela, departed Louisiana waters on October 28, 1863. Some of the vessels that had been requisitioned by the Federal government had been condemned and were candidates for “deep sixing”.

The leading edge of the storm hit the fleet on the 30th with rain, and then heavier winds produced ferocious conditions. Every vessel was put in jeopardy. Men lashed themselves to the sides with ropes, otherwise they would have been washed overboard. One sailor was swept overboard and drowned. Union losses were two steamers, two schooners and one tug. Fortunately all hands and passengers were rescued, however all artillery except two six-pounders, and all but 100 horses had either been thrown overboard on some ships or went down with the vessels. No ammunition was lost. Naturally the fleet convoy was dispersed.

The coast opposite Padre Island was reached the next afternoon. There was no opposition in sight, for the undermanned Confederate forces under General Bee had been ordered to withdraw from Fort Brown in Brownsville and the whole Coastal area of South Texas. This was fortuitous because the landing was made difficult by the storm-generated wave action on Brazos Island and through the shallow Brazos Santiago Pass.

Two sailors and seven soldiers drowned when a boat from the Owasco was swamped during the embarkation. Of 25 horses slung overboard by the 1st Texas Cavalry to swim to shore, only seven made it.