BY NORMAN ROZEFF

Upon the start of the Civil War Union forces stationed in the Valley soon were confronted by a overwhelming Confederate army that would allow them to evacuate the area.

The Steamer Daniel Webster with Maj. Fitz-John Porter, Assistant Adjutant General U. S. Army and part of General Winfield Scott’s staff, departed New York on 2/15/61 and arrived at Brazos de Santiago on March 3 to commence evacuating Federal troops.

On 2/21/61 Texas Confederate States of America (CSA) troops under Col. John Ford captured the U.S. Depot with its mortars, siege guns, and ordnance in the town of Brazos de Santiago on the north end of Brazos Island. General John B. Magruder of the CSA ordered the blasting of the Point Isabel Lighthouse, but, when executed, it was only damaged. Later its lenses were removed and buried in the backyard of Ford’s Brownsville residence.

Little was accomplished along the South Texas coast until, on 12/5/61, a naval blockade was organized at Point Isabel. This was extended to Brazos Santiago on 2/25/62, one of the participating Federal vessels being the U.S.S. Portsmouth, a 22-gun sloop of war. On the evening of May 27, 1863 the U.S.S. Brooklyn, a steam sloop under the command of Commodore H. H. Bell, anchored off the mouth of the Rio Grande.

“The next morning Bell counted sixty-eight sails at anchor off the bar ‘and a forest of smaller craft’ inside the river.” Spotting a mast to the north the Brooklyn got underway and was to seize the sloop Kate with its crew of three and its cargo of 18 bales cotton that had been loaded in Houston and had sneaked into the Gulf at Valsaco. He brought the prize cargo aboard.

Turning south again, the crew spied two sloops and two schooners inside Brazos Santiago. On the 30th the Brooklyn anchored off this pass and sent four small boats with 87 men over the Brazos Santiago Pass bar into the bay to capture the four vessels involved in smuggling and also, if possible, to spike the three guns at Point Isabel. [Note: Brazos Santiago Pass is that now defined by the jetties projecting from the extreme south end of South Padre Island and the northernmost extent of Brazos Island].

The party returned with the 100-ton schooner Star and a fishing scow with two men. Point Isabel natives, upon seeing the approaching expedition party, had set fire to the other schooner as well as a house on the point. The party however did capture the sloop Victoria, a Jamaican ship of 100 tons carrying a mixed cargo. It was run aground and torched. (An alternate Confederate account has the vessel accidentally run aground and set ablaze by the hasty actions of the retreating Union sailors.) The Union sailors did recover a quantity of goods that the Victoria had left on the wharf. These included 12 boxes of medicines, tin and spelter (used in galvanizing tin). One Union sailor, John Newman, was lost when a marine accidentally discharged a musket at him.

By June 1 the Brooklyn had returned to patrol duty at Galveston. In its activities near Point Isabel it had captured en toto 57 bales of cotton, 12 boxes of sundries, the sloops Kate and Blazer, the schooner Star, and taken 10 men captive. With the inconsistent blockade of the Pass, Mexican lighters from the Rio Grande landed here in Sept. 1863 with a large cargo of arms for the Confederate States of America.

In the first half of 1864, the Union supplied Fort Brown by mule teams from Point Isabel. Upon the Union retreat from the fort to Brazos Island in late July 1864, Point Isabel, being borderline defensible by the Confederate army, became a “no man’s land.”

Upon the end of the Civil War in 1865, Union forces were sent to secure the border from a possible Confederate backlash from CSA soldiers that had fled into Mexico but also to discourage any incursion from Maximilian’s armed forces then in Mexico. General Phil Sheridan was the commander of the forces here when huge military supplies were being landed as viewed by observers on Woodhouse’s Bluff.

An early survey of the pass and bay was made between January and March 1871, and seven years later Congress appropriated $6,000 to remove a wrecked French vessel from the pass. Between 1878 and 1889 seven appropriations totaling $253,500 were made for harbor improvements, but not all was spent.

Although the United States had secured the town in 1846, it wasn’t until about sixty years later around 1906 that the “typically Mexican” plaza of the town was lost. The plaza had contained a kiosk, dancing and promenade areas surrounded by restaurants, candy vendors, and gaming tables. Wagons were the prime means of moving good to and from the port.

As the Valley grew Brownsville businessmen lead by Simon Ceyala organized to form a railroad company that would connect the port to Brownsville. This was in the year 1871.

Two schools of thought divided the directors as to where the terminus should be located. Some favored the small village area north of the lighthouse while others wanted the largely vacant areas south of the light. Those for the former also wished to see the route of the line to Brownsville take a longer circuitous route on higher and drier ground.

Celaya’s contingent opted for the end of the line to be south of the lighthouse and for a shorter route which would carry it over lagoon areas. Celaya’s group won out, but their decision would later prove a costly one.

The Brownsville newspaper carried ads reflecting the line began operation in 1872.

The constructed pier that jutted out into the Laguna Madre from Point Isabel was originally made with palm tree pilings. After an 1880 storm severely damaged it the piling were replaced by those of cypress with the bottom of the timbers encased in copper sheathing to deter teredo worms, a species of salt water clams.

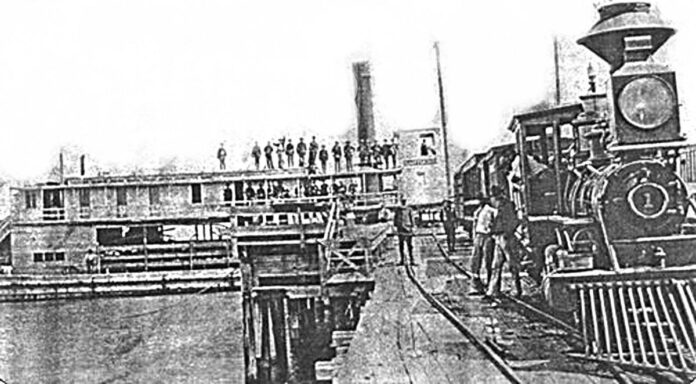

In 1918 the piling again were replaced this time by creosoted timbers. Sometimes 30 to 40 shallow draft steamships entered the port in one month’s time. The Morgan Line steamers made the Brazos Santiago port a regular port of call. More affluent visitors to the Valley favored ocean travel over the slow and rough stage coach line. Connecting transportation was facilitated when, on July 4, 1872 the Rio Grande Railroad was inaugurated from Point Isabel to Brownsville.

Simon Celaya’s 22.5-mile line was of an odd gage, more narrow gage than standard. “The railroad also operated steam and sail lighters from its quarter-mile-long wharf at Point Isabel to the Brazos Santiago harbor, a distance of three miles.” Unfortunately for the area much changed after 1882 when Corpus Christi was connected to Laredo by a standard gage railroad. Valley transportation then became relatively isolated.

Celaya’s railroad and its successors would have many ups and downs and name changes over its history. As a side note the side- wheeler Adelaida, the last of the Rio Grande Railroad lighters, was grounded in the shallow Laguna Madre and its skeleton finally broken up by the 1933 hurricane.