SAN JUAN — More than 100 people marched Sunday commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Texas Farmworkers March for Human Rights that started here on Feb. 26, 1977, and ended more than three months later in Washington D.C.

A corrido relaying their historic journey titled “La Marcha del Campesino” by Esteban “El Parche” Jordan played in the background as demonstrators waving Texas Farm Workers Union flags and banners reached St. John the Baptist Catholic Church.

At the church gates, the crowd gathered around Abel Orendain who, standing on the spot marchers began their 1,600-mile journey 40 years ago, read his late father’s words.

“Upon leaving the Garden of Eden, man would have to live by the sweat of his own brow,” he said through a loudspeaker. “Under the free enterprise system one must have a profession, education, or money. We farmworkers have chosen to work the land, and only ask to have the right to put a price on the sweat of our own brow.”

His father, Antonio Orendain, was the original secretary/treasurer of the United Farm Workers Union in California. He arrived to Rio Grande City in 1966, where farmworkers were on strike against the melon growers. In 1969, Orendain decided to make the Valley his permanent home and moved his family here. Here he worked to establish a union presence until 1975, when Orendain separated from the UFWU and founded the TFWU.

He passed away in April 2016 at the age of 85 after a lifelong fight for civil rights.

Leading the more than 100 marchers was Gilbert Ramirez, 64, and Claudio Ramirez, 48. They each stood at the end of a faded red banner with the image of the Virgen de San Juan and the words Texas Farmworkers stitched under it in gold.

“We carry this in honor of my father and the farmworkers and their fight for human rights which continues today,” said Gilbert, holding the same banner his father carried during the original march.

“I feel very proud and honored to be able to march and carry this banner just like my grandfather did,” said Claudio, who was named after his grandfather. “They were fighting for basic things, like water, bathrooms and fair wages.”

Much like the UFW led by Cesar Chavez, the TFWU was also fighting for collective bargaining rights, except they are sometimes overlooked and forgotten, according to Norma Ramirez who organized the march alongside Fuerza del Valle Workers Center in Alamo.

“We need to keep this story going,” she said. “This story is getting lost because a lot of people get us confused with the United Farm Workers.”

“A lot of credit is given to Mr. Cesar Chavez, and believe me I have nothing against him and we need to give credit where it’s due, but when it came to Texas it was not Cesar Chavez, it was Antonio Orendain who organized these people and fought for the people here in Texas, and I think that’s something that is getting lost,” she added.

Ramirez turned 15 years old on the day the marcher’s reached Austin, where they met with Gov. Dolph Briscoe. She said after their meeting they were unsatisfied by the lack of results and decided to continue their march to Washington D.C. in June 1977.

The march began with a group of about 40 farmworkers who would walk about 20 miles per day, staying in public parks or church halls along the way. The march quickly gained support and grew to about 10,000 when they arrived to the nation’s capital where they planned to meet with President Jimmy Carter. But after Carter refused, they picketed around the White House but were not allowed in.

Dolores Rosel, 71, said she will never forget that day in D.C. She was pregnant throughout the entire march and on the same day they arrived she gave birth to her daughter.

“It was five in the morning, when we arrived,” Rosel said in Spanish. “We were next to the White House when I started feeling bad and they took me to a hospital and she was born that same day. My daughter is the same age as the march and she is here today with her own children.”

Joseph Orendain, 53, was 14 when he joined his father on the march. He said at the time President Carter was advocating for human rights in foreign countries and they were trying to make him to look in his own backyard.

“That’s where the people needed help. The campesinos need help, they need to be able to put a price on their own labor,” he said. “That was the whole point of the march.”

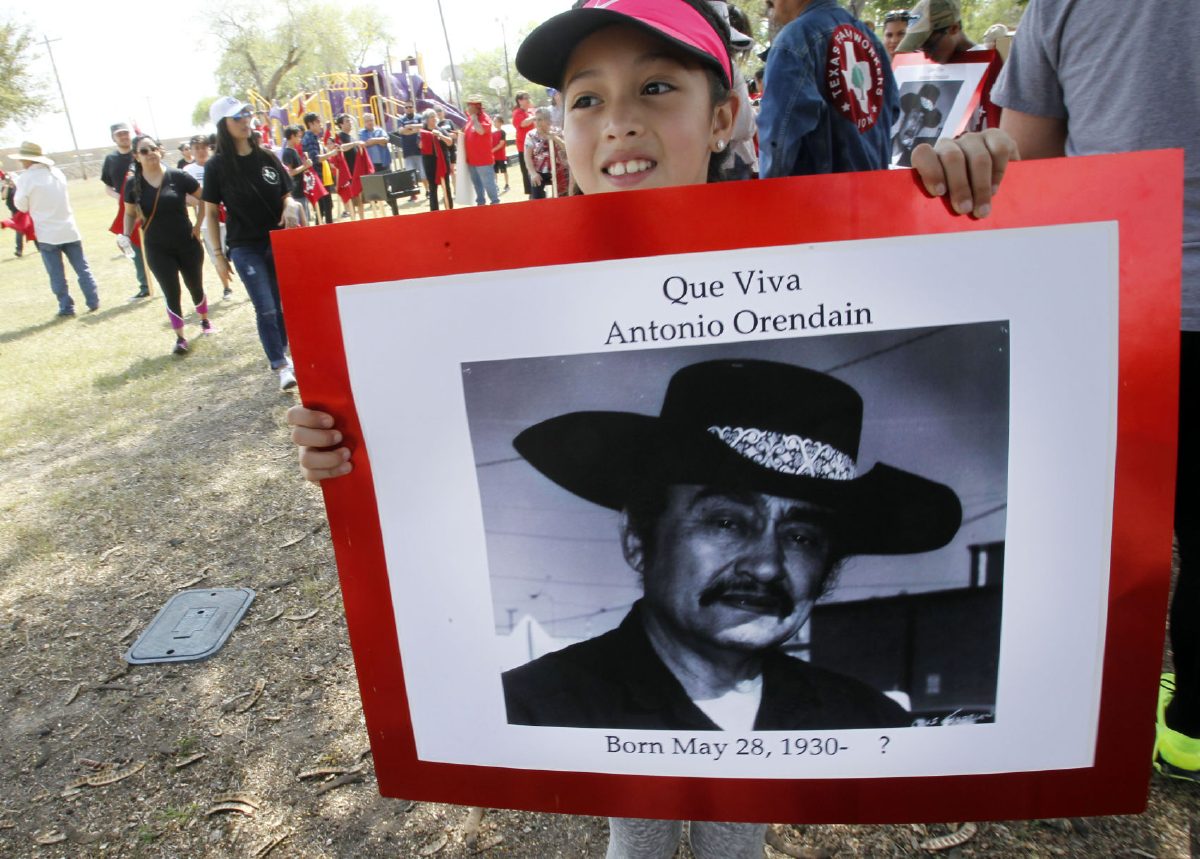

His 13-year-old son, Joseph Anthony Orendain, marched Sunday holding a photo of his grandfather wearing his infamous black hat and the words “Que Viva Antonio Orendain, Born May 28, 1930 – ?” written on the black and white picture.

“We felt the question mark was emulating the poster of Zapata and Pancho Villa that I used to see growing up that my dad had, because the spirit lives on, it never dies,” he said. “The fight for civil rights and the fight to be treated humanely never dies, so his spirit never dies.”