Brownsville police officer Regino Garza has encountered autistic people while patrolling the streets.

Authorities said Brownsville has a large autistic community — probably larger than some would believe.

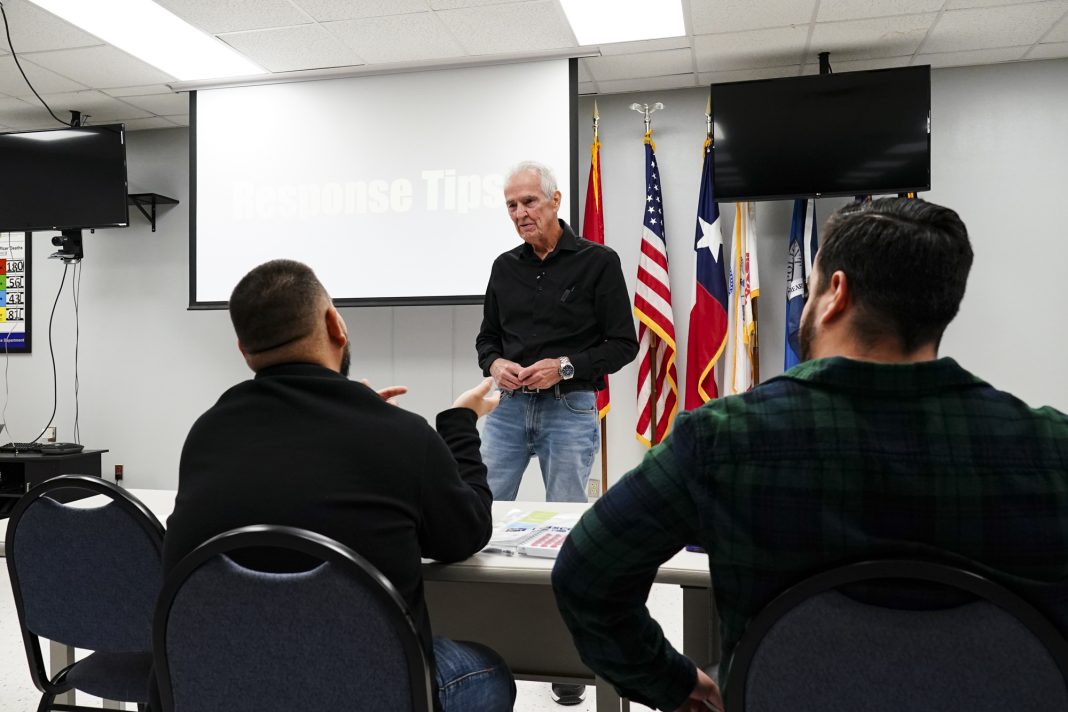

Driscoll Health Plan, in collaboration with Brownsville Police Department and Bebo’s Angels, held an Autism Risk & Safety Management Training program Wednesday for Brownsville’s police officers.

Dennis Debbaudt, of Debbaudt Legacy Productions, LLC, was the presenter.

“The information they put out to us is really helpful for us because we do encounter a lot of people with autism…it’s a big misconception when people call us that they (the autistic) person is drunk or doing drugs because of the type of movements they do sometimes, but that is not the case at all,” Garza said. “This training along with others is extremely helpful to us, when we get there. It helps us quick.”

About three years ago, parents were provided with Law Enforcement Special Needs Awareness decals that could be placed on their vehicles. The blue-colored stickers indicated a child with autism was riding in the vehicle to alert police.

“I personally have responded to several cases where the kids are flaring up with little tantrums. There’s only so much we can do. The parents themselves are the ones who should also be getting some training for this,” Garza said.

Current statistics show that 1 in 44 people in America suffers from some type of autism. In 2000, statistic showed 1 in 150 people suffered from some type of autism.

Garza said while the numbers may sound alarming, they really aren’t because just about every police officer on patrol has encountered a person with autism once a day or once a week.

Nationwide, autism has grown from half million to 7 million, said Debbaudt, who provides training to law enforcement officers on how to deal with autistic people they encounter.

There are more identified autistic people in America now than ever before, and the numbers are incredible, he said.

Although Debbaudt talked about the types of autistic people the officers my encounter while on patrol, he said the primary goal is “officer safety…if at times you don’t feel safe screw the tips (I am giving you) and everything else and maintain your safety.”

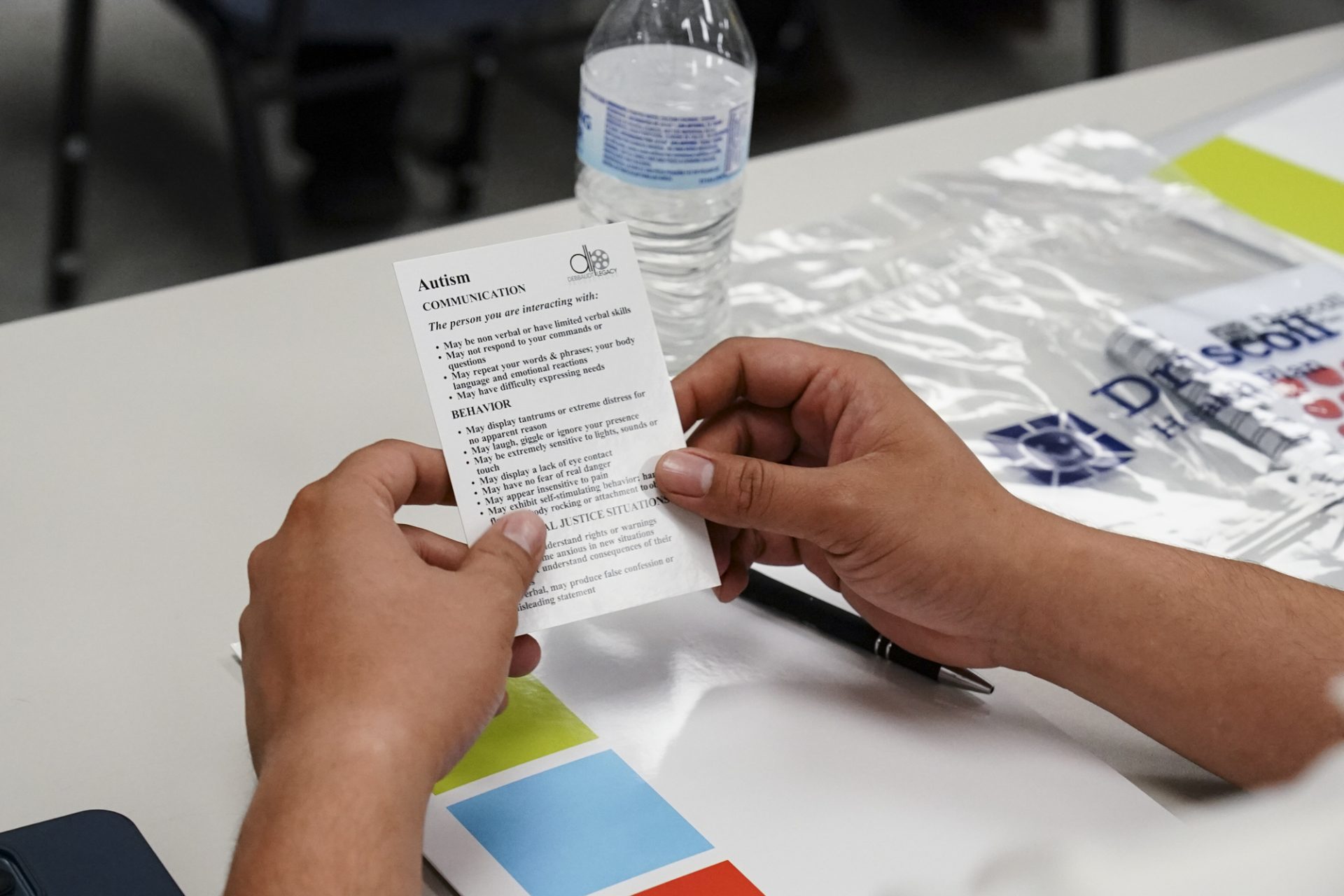

Debbaudt provided the officers with a card on tips on how to stay safe when dealing with a person who has autism. Some of the tips include displaying calm body language, using simple language and to speak slowly, repeat and rephrase questions.

As part of Wednesday’s training, the officers watched a five-minute video that showed two officers responding to a suspicious person call, which later turned out to be an autistic man. The officers first questioned the man before determining that something was not right and helped him get back to his family. They had not idea that he suffered from autism.

According to Debbaudt, as with Alzheimer’s patients, persons with autism may wander. In addition, persons with autism may be attracted to water sources, roadways, or peer into and enter dwellings.

Information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pertaining to autism indicates that autism affects all races and socioeconomic groups and that it is four times more common among boys than among girls.

In addition, about one in six or 17% of children between the ages of 3 to 17 were diagnosed with a developmental disability, as reported by parents during a study period of 2009-2017. These include autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, blindness, and cerebral palsy, among others.

Debbaudt said it is important that presentations such as the one he gave Wednesday be provided because the diagnosis of autism has become so frequent in America and that the contacts autistic people are having with law enforcement are becoming more frequent.

“Within that population, because it’s a behavioral and communication disability, it can pose problems understanding and reacting well and giving people time and space and simple communications is the key,” he said.