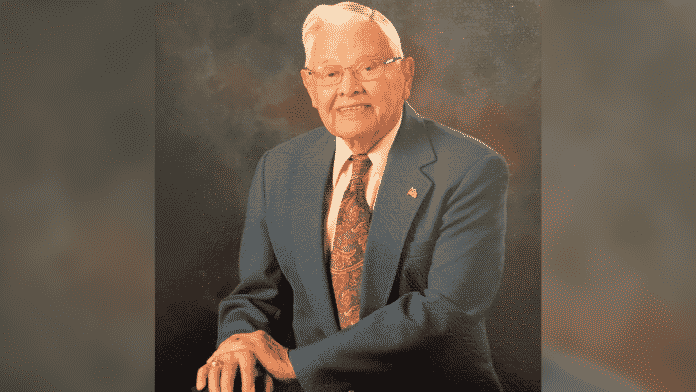

MISSION — Oton “Tony” Guerrero had two homes on Mayberry Street: the small house he grew up in with 10 siblings, and Citriana Elementary School.

Guerrero was principal when the Mission elementary campus welcomed its first batch of students in 1959, making him the first Hispanic principal of the Mission school district.

“Mr. G was the one who opened the gates for Hispanics here,” said Hilda Escobar, the first Hispanic woman to become principal for the district.

She, like many other principals, administrators and teachers from across the region considered Guerrero a close mentor.

After paving the way for other Hispanic education leaders to rise in the region, and a long career dedicated to supporting Valley students, Guerrero died on Jan. 2 at the age of 96.

Growing up down the street of the school where he worked, Guerrero understood the poor living conditions some of the students of MCISD faced all too well. He also understood that diplomas and college degrees were the keys to better lives for students — so he pushed them.

The love he had for his hometown of Mission fueled his earnest passion for helping students excel in school.

Guerrero started his educational career as a teacher in Edinburg, which he did for six years before becoming principal of Citriana. He renamed the school Capt. Joaquin Castro Elementary School after his uncle in 1952, and stayed there for almost a decade before moving to the then University of Texas-Pan American in 1968 to be a physical education professor, and preside as the school’s top golf coach.

After serving in the Navy during World War II as a teenager, Guerrero graduated from Mission High School. He then completed his bachelor’s degree in at the then Texas College of Arts and Industries in Kingsville, where he later earned a master’s degree in public school administration.

He had six children with Emma Cabaza-Guerrero, and the youngest among them, Dolores Reyna, said nothing made her father happier than helping others get an education.

Reyna was 6 years old when he took on the position of principal of Citriana.

“That was his home away from home, and all I know is that he was happy when he was there,” she said, a former Valley teacher of 30 years.

“He just wanted what was best for students — that was always his heart.”

Growing up in Mission during the early 1900s, Guerrero had to attend a school specifically for colored students. So when the school district accepted Guerrero as its first Hispanic principal, he knew there wasn’t a reason for Valley students not to succeed.

“He always stood up for the kids,” said Escobar, who retired from Mission CISD in 1996. “He would say, ‘Yes they’re poor but they are eager to learn.’

“He was an education giant that believed — truly believed — that children had the ability to become whatever they wanted, to do whatever they wanted, that they just needed to be guided and focused on education.”

When Reyna looked through her dad’s office, she found several certificates he kept of perfect attendance achievements during his years as principal; during the 1964-65 school year, not a single third or sixth grader missed a day of school.

“Oh he made sure they went to school, he made sure his students knew there were no excuses for missing school,” Reyna said, remembering there were times he would pick up students himself and take them to school.

She also recalled that there were some days when students would tell him they couldn’t go to class because they didn’t have shoes to wear. So, he picked them up to buy shoes, and then brought them to campus.

Guerrero also knew that to best help his students, he had to support their parents, too.

During his time at Citriana, he founded the district’s first Parent Teacher Association, in which parents were able to get involved in leadership roles in the school, and during the evenings, Guerrero would host English classes for them.

“It was the first time someone opened a school at night for parents to learn English,” Reyna said. “He would teach the class, and a lot of the parents that came were farmworkers who worked during the day, so this was their only opportunity to learn English.”

Guerrero, just the way he did to his children and grandchildren, pushed his teachers to strive for higher degrees.

The administrative roles of some of his former staff now depicts how the roots of his legacy run deep through the region’s education system.

Guerrero mentored teachers who became principals that have become the namesakes of several of the district’s schools, such as Leal Elementary School, MidKiff Elementary School, and Escobar/Rios Elementary School.

Escobar, the namesake of Escobar/Rios, said Guerrero was the reason she found the courage to pursue her master’s degree.

Guerrero treated the teachers like his own family. At the time, the closest university to get a master’s was in Kingsville, and Reyna said there were some nights he would drive groups of his teachers to campus because he didn’t want them to commute alone.

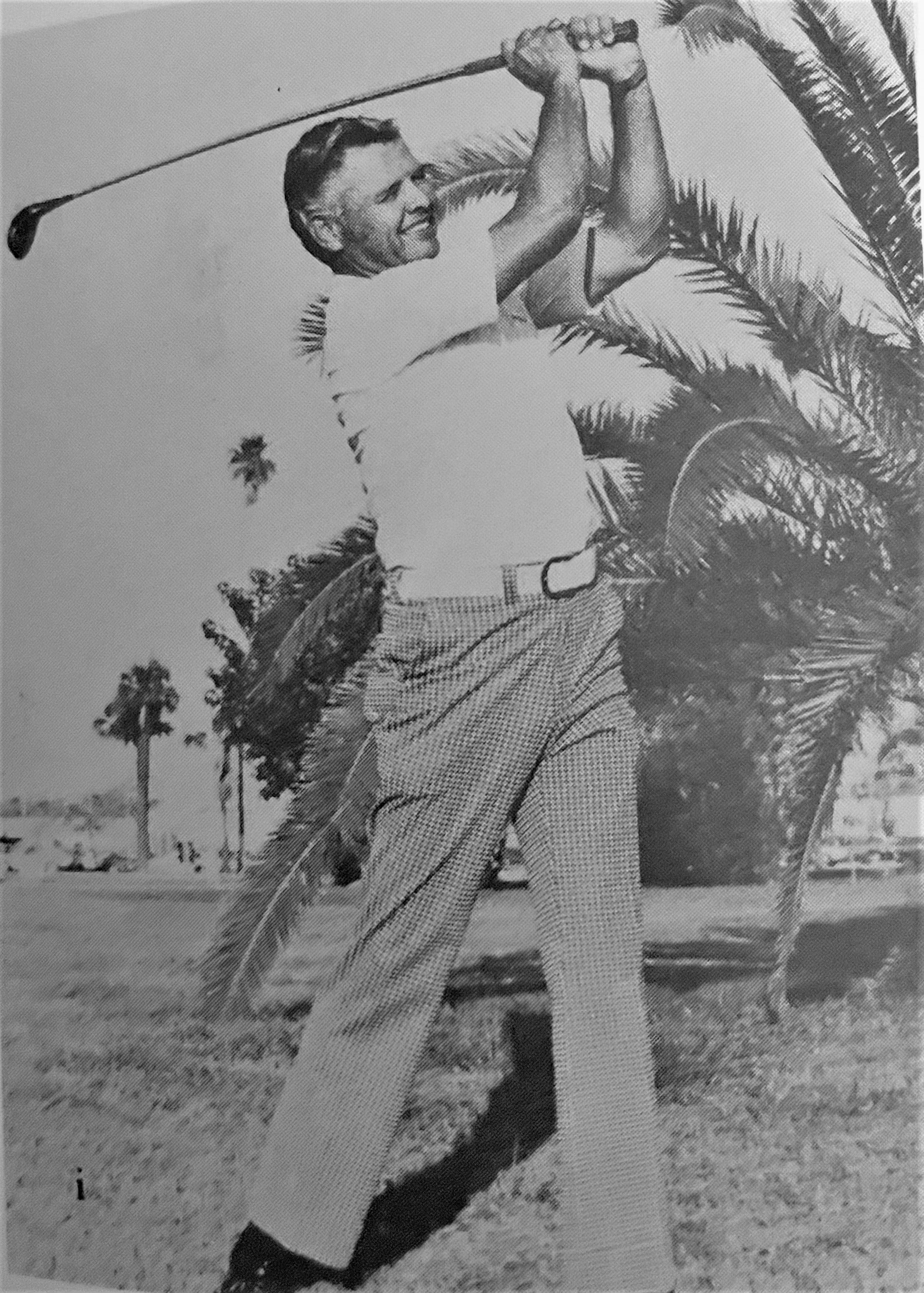

As a golf coach at UTPA, now UTRGV, Guerrero invited and trained players from around the world. He also never let go of the principle that school came first, achieving a 96% graduation rate among his players.

At the university, Guerrero founded the International Collegiate Golf Tournament, which drew professional players from across the nation, including World Golf of Fame member Ben Crenshaw.

Guerrero received many accolades for coaching golf, including being inducted into the All-American Intercollegiate Golf Hall of Fame, the Rio Grande Valley Sports Hall of Fame.

He retired at 73, but telling from how much he loved his job, Reyna said her dad never worked a day.

“It was like he was retired already because he loved his job. Whatever job he had he loved it and did it wholeheartedly,” she said.

Faith played a major part in Guerrero’s life, and served as the foundation of everything he did. He was a member of the Knights of Columbus for 60 years, and served as minister of St. Paul’s Catholic Church in Mission.

After he died, Reyna found a small bag with 13 rosaries — one for each of his grandchildren.

She said the most difficult part of living through the pandemic for him was not being able to participate in communion. Since he was homebound a few years ago, members of the church would come to his home for the communion. When COVID-19 hit, they stopped.

The fruits of Guerrero’s dedication to the Valley’s students will be abundant and unending, Escobar said, so long as they continue to go to class and work hard.

“That was his heart: education,” Escobar said. “That was him; he symbolized education, the best success for all the kids.