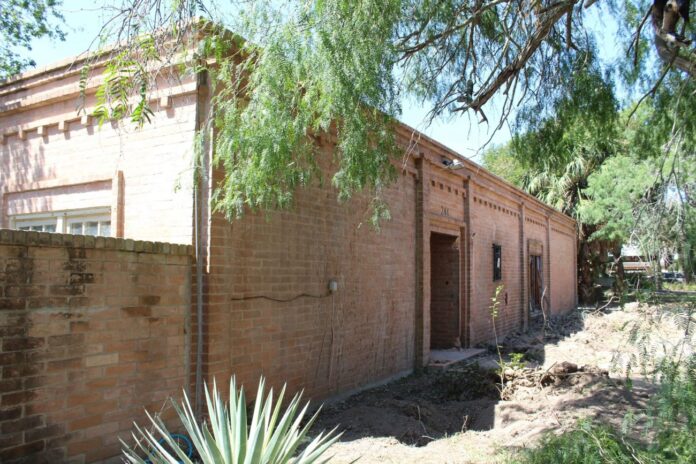

The 1962 J. Kendall Hert House, designed by Ruth Young McGonigle, was considered a rare example of a mid-century modern residence incorporating elements of classic, border-brick-style architecture, and especially notable for being designed by the first woman to practice architecture in the Rio Grande Valley.

The house, at 244 Calle Cenizo in the historic Rio Viejo subdivision, was bulldozed recently. Nothing remains but photographs and drawings done at the last minute. Stephen Fox, a Houston-based architectural historian and Brownsville native who teaches at Rice University and the University of Houston, said the demolition is a loss.

“I think it was one of the outstanding works of Ruth Young McGonigle,” he said. “She stood out as an early woman designer.”

McGonigle was the first woman to graduate from the Rice Institute, later Rice University, with a bachelor of science degree in architecture, which she studied in order to be able to take art classes. The Spindletop native graduated in 1924 and married her former classmate George McGonigle Jr. in 1925 before moving to his hometown, Brownsville. He died in a plane crash nearly 30 years later.

“She was never registered as an architect,” Fox said. “After 1938 in the state of Texas if you wanted to call yourself an architect you had to be registered with the state of Texas as an architect, so she was careful not to describe herself as an architect, but she was trained as an architect. I think particularly after her husband was killed in the mid 1950s she, out of pure economic necessity, needed to earn an income.”

McGonigle made her living primarily designing single-family houses though she also designed a number of public buildings, including St. Paul’s Episcopal Mission and the Brownsville Museum of Fine Art. Fox said the Hert House stood out because the design was based on the border-brick style that prevailed along both sides of the lower Rio Grande in the 19th century. He remembers growing up in Brownsville in the 1960s, when people didn’t see much value in the old structures.

“People really just looked at buildings of the 19th century as kind of old and slightly embarrassing, that Brownsville was saddled with all these old buildings instead of nice, new, modern,” Fox said. “I think it took someone with Ruth McGonigle’s eye — and I think she was really first and foremost an artist, and kind of an architect by necessity — to be able to look at this architectural historical heritage and see that it actually was something very distinctive, and moreover could be adapted for new construction, that it didn’t just have to remain in the past, but it was a way of affirming the cultural value of this local cultural heritage.”

McGonigle, who died in 1984, was a founding member of the Brownsville Art League, later the BMFA. Rio Viejo, the 118-acre subdivision developed in the early 1950s by Harlingen real estate developers Paul Carruth and W. Vernon Walsh, has lost other notable houses — not necessarily to demolition but rather to bad remodeling, Fox said. In this category is a mid-century modern residence designed by the renowned Harlingen-based architect Alan Y. Taniguchi, who also designed the mid-century modern First National Bank building on East Levee Street in Brownsville. Today the Rio Viejo Taniguchi house is unrecognizable, Fox said.

Houses designed by the well-known, mid-century modern architects William C. Baxter and John G. York survive in Rio Viejo, in various states of repair, though the subdivision primarily features mid-century, builder-designed, one-story ranch homes that, even if not architecturally significant themselves, nevertheless reflect the original “garden home” look of the neighborhood. The subdivision also contains several “architecturally inconsequential” newer houses on sites where the original houses once stood, Fox said.

Unlike the nearby Los Ebanos historic subdivision, where a McGonigle-designed residence, shrouded in ivy, still stands at 225 Sunset Drive, Rio Viejo has no historic district zoning overlay to protect important buildings. The city attempted to impose such an overlay in 2013, though the effort was met with stiff resistance by some Rio Viejo residents and the initiative was dropped.

Juan Velez, the city’s historic preservation officer since 2016, said owners who preserve architecturally important properties are saving them not just for themselves but for the community. Short of an overlay, the only way to guarantee Rio Viejo’s remaining important houses won’t be demolished is to work with owners to get them listed on the state and national historic registers, he said. Having a property so listed affords the owner substantial financial incentives to maintain the property in a manner that preserves its significance, Velez said.

Meanwhile, Velez, who was born in Brownsville but grew up in Spain, said Europeans see mid-century modern as the first truly American architecture and that it’s “surprising and sad every time an example is lost.”

Serena Putegnat, who lives in Rio Viejo in the house she grew up in and was among those who pushed for the overlay back in 2013, said it was never intended to be controversial, though if it were attempted again it would probably fail. She agreed that state and national historic designation for individual Rio Viejo properties is the way to go, while bemoaning the endangered status of mid-century modern buildings in general.

“This is not just a Brownsville problem,” Putegnat said. “It’s all over the nation. I don’t think that people think that mid-century modern architecture is worth preserving, because it’s only 50 or 60 years old, and if it was like a 100-year-old building people would be scrambling to save it. … San Antonio’s having problems of their own. Alamo Heights is in danger. West (University) in Houston, they’re in danger.”

There’s also the issue that the most significant buildings being lost were the product of someone sitting down and putting a lot of thought and energy into creating a liveable space to suit a specific setting — a work of art, essentially, she said. Putegnat said she’d hate for McGonigle to know that the beautiful little house she designed had been torn down.

“She was such an important lady for Brownsville,” she said. “And the retro style is in style. So I don’t understand why you would tear it down. Avocado green tile is in.”