As the private and public sectors are pushed further into the digital age, lawmakers at every level of government are searching for ways to expand internet infrastructure.

Soon, the federal government will begin distributing $42 billion across the country to aid in the mission of closing the digital divide.

But advocates and state officials say the data they plan to use to determine who gets what could mean the Rio Grande Valley doesn’t see its fair share.

INTERNET IMPASSE

In Starr County, where unobstructed landscapes yield a clear view of the Monterrey mountains, families living in sparsely developed towns struggle to give their children an equal opportunity for education.

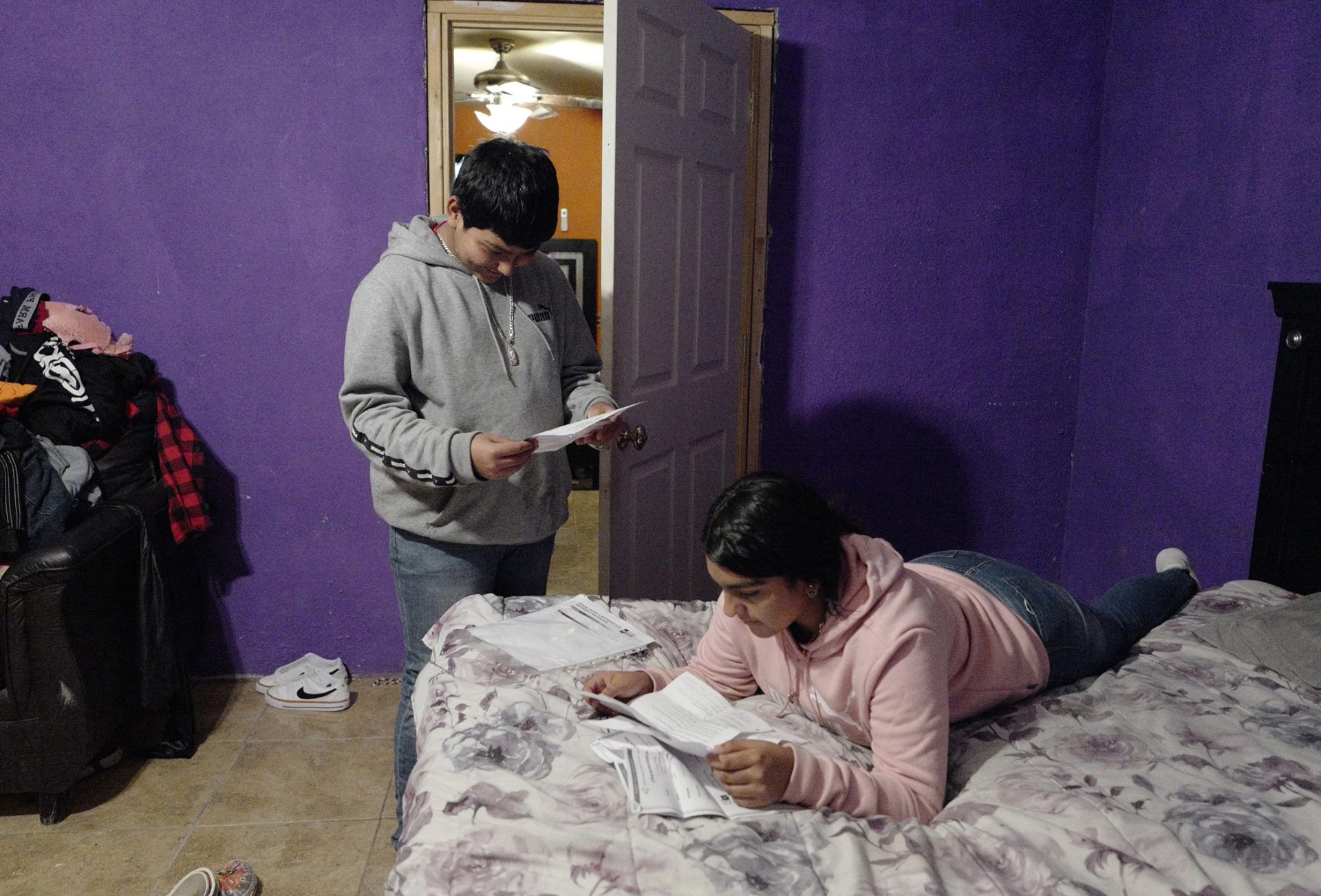

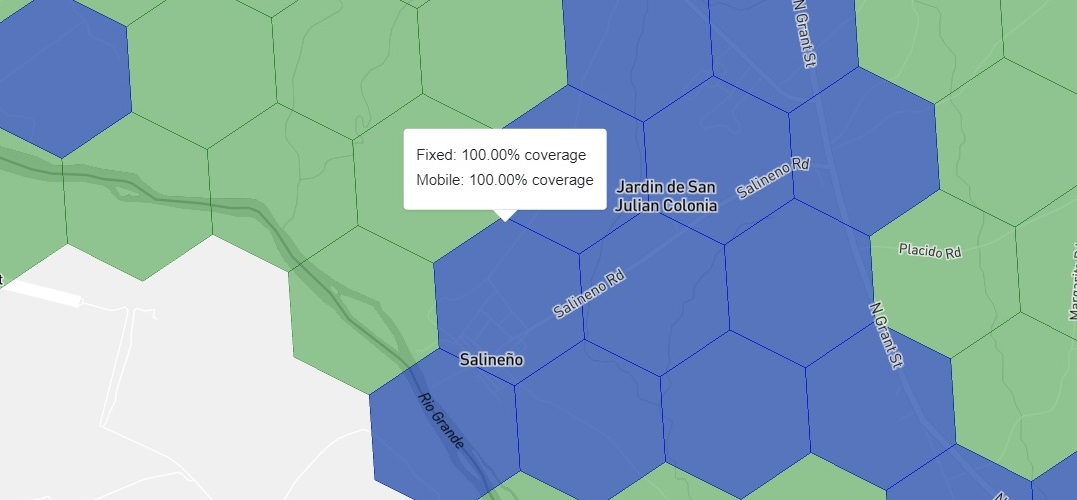

Perla Talamante, 37, lives atop a hill overlooking the road winding down through Salineño, just 2 miles from the river dividing the U.S. from Mexico.

Talamante sustains her four children on a single annual income of about $26,000, without child support, and lives in a small two-bedroom home behind her parents’ house.

Her children — Samuel, 11, Lyanna, 12, Mia, 16, and Xiomara, 17 — attended Roma ISD schools during the pandemic, but when classrooms went virtual, the Talamantes couldn’t always keep up. The demand for electronic devices and internet access became a stumbling block the school district attempted to help them overcome.

Talamante’s children received Chromebooks and a hot spot to help them connect online.

Internet service was unpredictable and easily affected by the weather, Talamante said. It gave out multiple times during the day, kicking the kids out of the classroom.

“It’s kind of slow,” Talamante recalled. “Imagine four Chromebooks at the same time. So, it was really hard.”

Talamante works as a caregiver for her parents who live a few steps from her home, but the constant problems meant she had to split her attention between her job and her children.

“I had to send a WhatsApp to the teacher and let her know that it wasn’t working,” she said.

The FCC Household Broadband Guide suggests a household like the Talamantes, which uses four devices for video conferencing, requires an advanced data plan that offers speeds of 25 megabits per second.

Between the challenges to connect and those posed by short attention spans and no on-site teachers, the grades began to slip. Teachers helped the children adjust and would require cameras to be turned on to keep an eye on students.

Video cameras, however, placed a higher demand on an already-overburdened hot spot.

Aware of the hot spot shortcomings, school districts pivoted to different methods to help boost internet access across the Valley.

Here are broadband household recommendations from the FCC.

UNRELIABLE SOLUTIONS

In Hidalgo County, Donna ISD’s school board decided to invest $3.7 million to contract the construction of several towers to amplify internet access in areas known to have little to no access.

Maria I. Azuara, 40, a mother of three in Donna, and her husband, Efren Robles, 37, were one of the families who received assistance from their children’s school district when the pandemic began.

The couple has lived in their rural home for 15 years where internet service providers, or ISPs, had yet to set down any infrastructure to provide access when their children were required to attend classes online.

Like 52% of Donna ISD families, Azuara and her family did not have internet access. At first, they received a hotspot which was later upgraded. They received equipment that would connect to the newly created internet towers.

Azuara’s daughter, Izabella, 5 at the time, would need to sit at the dining room table on the chair closest to the window to try to sign on to her online class. The equipment, which appears to function as a repeater site, was just feet away outside by the fenceline.

The 12 towers Donna ISD provided were scattered around the city, although largely concentrating in areas near Military Highway 281 in south Donna.

The antenna placed outside Azuara’s home, attached to a utility pole, received the signal from one of the nearby towers and sent the connection down through a wire drilled into the home connected to a router.

Every time it rained, that was it; there would be no internet,” Azuara said. “If there was wind, there was no internet. There was never hardly any internet.

Azuara recalled a time the family spent an entire week without service.

Logging on to classes became difficult for the two youngest kids, Izabella, who was in kindergarten, and Angel, 11 at the time, who was in sixth grade.

Before the pandemic, Angel went to school every day and earned perfect attendance records. But when the internet dropped off, he was often not allowed to log back into the classroom, his mother said.

Over time, Angel’s grades dipped.

“I would always see that he would bring back 90s, but one day I noticed a 42 on his report card,” his mother said. “‘It’s because he doesn’t connect, ma’am,’ teachers told me. ‘He does connect online, but the internet stops working and he’s not allowed to sign back on,” she replied.

Even though Angel’s mother and father both held jobs at the time, they decided to take him to school where he was able to improve his grades.

Back home, Izabella struggled to pay attention online.

It was very difficult for the teachers, but also for the children because they didn’t learn,” Azuara said. “She learned nothing, nothing. For me it was a lost year.

Even now, Izabella is in the second grade and still struggles to read.

“So far she’s just starting to put letters together,” her mother said.

Angel frequently helps her with her homework.

Unreliable service and a lightning storm completely severed services offered by Donna ISD. Now, the repeater device stands idly on the pole outside Azuara’s home while the district fights a lawsuit over the failed tower project.

Last year, Spectrum finally worked with residents to get permission to enter their property and stretch out fiber cable over utility poles in their backyards. Azuara subscribed and now pays about $150 per month for internet, cable and a landline.

ROADMAPS TO FUNDING

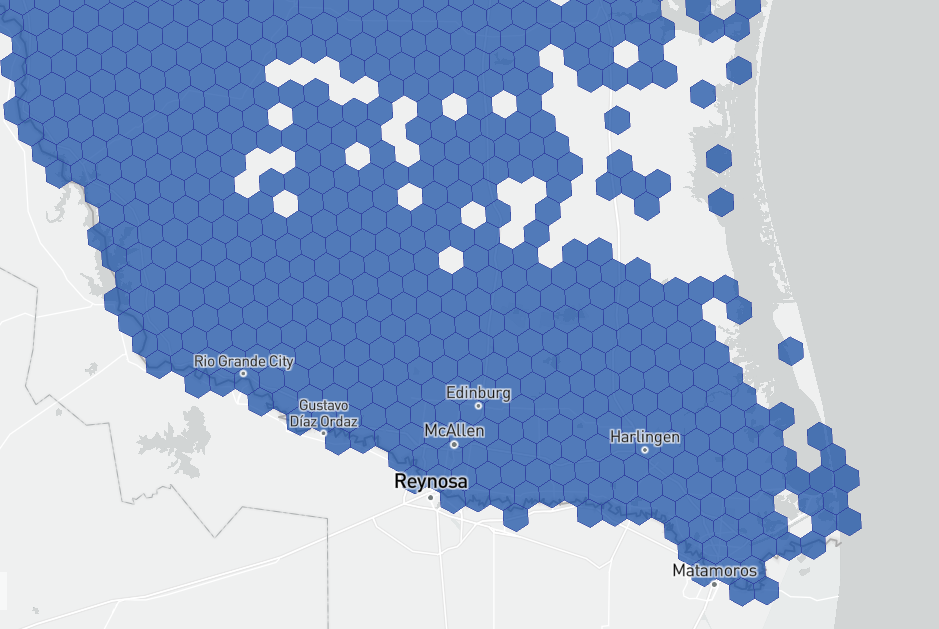

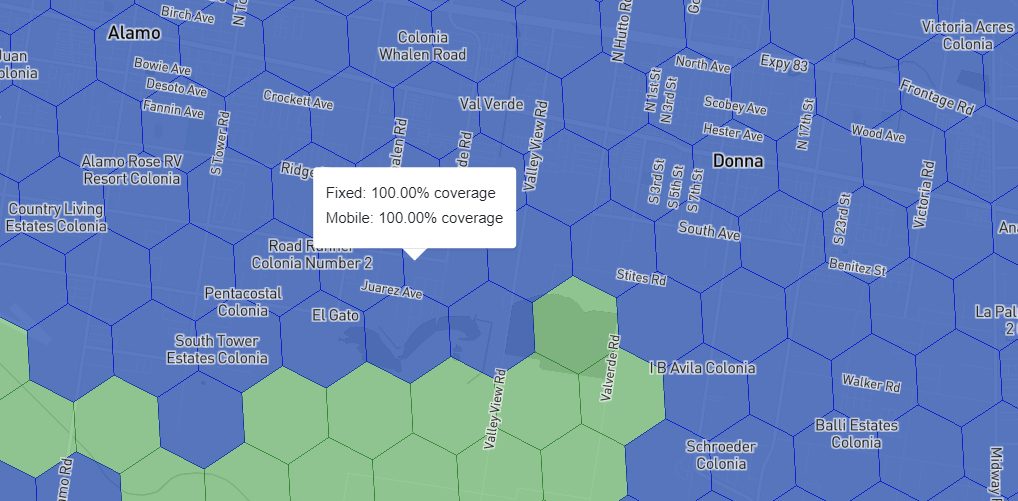

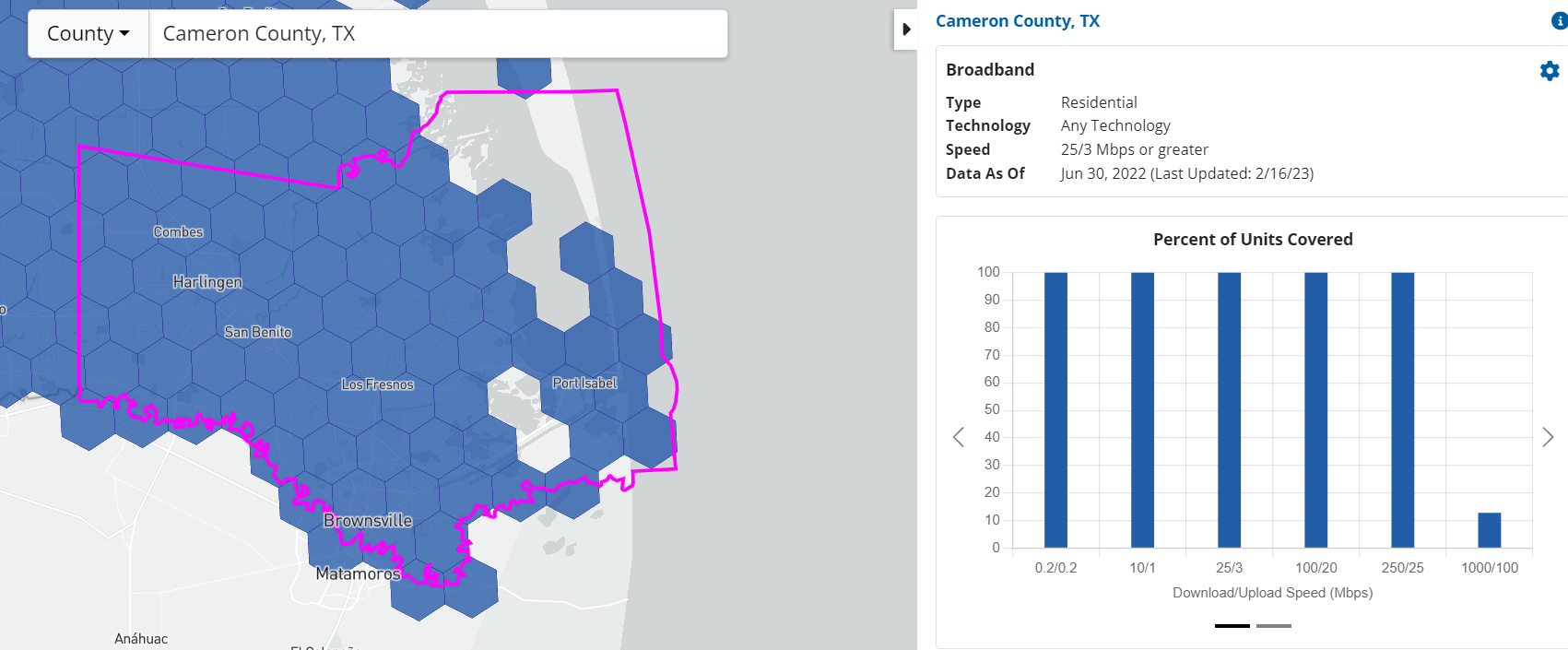

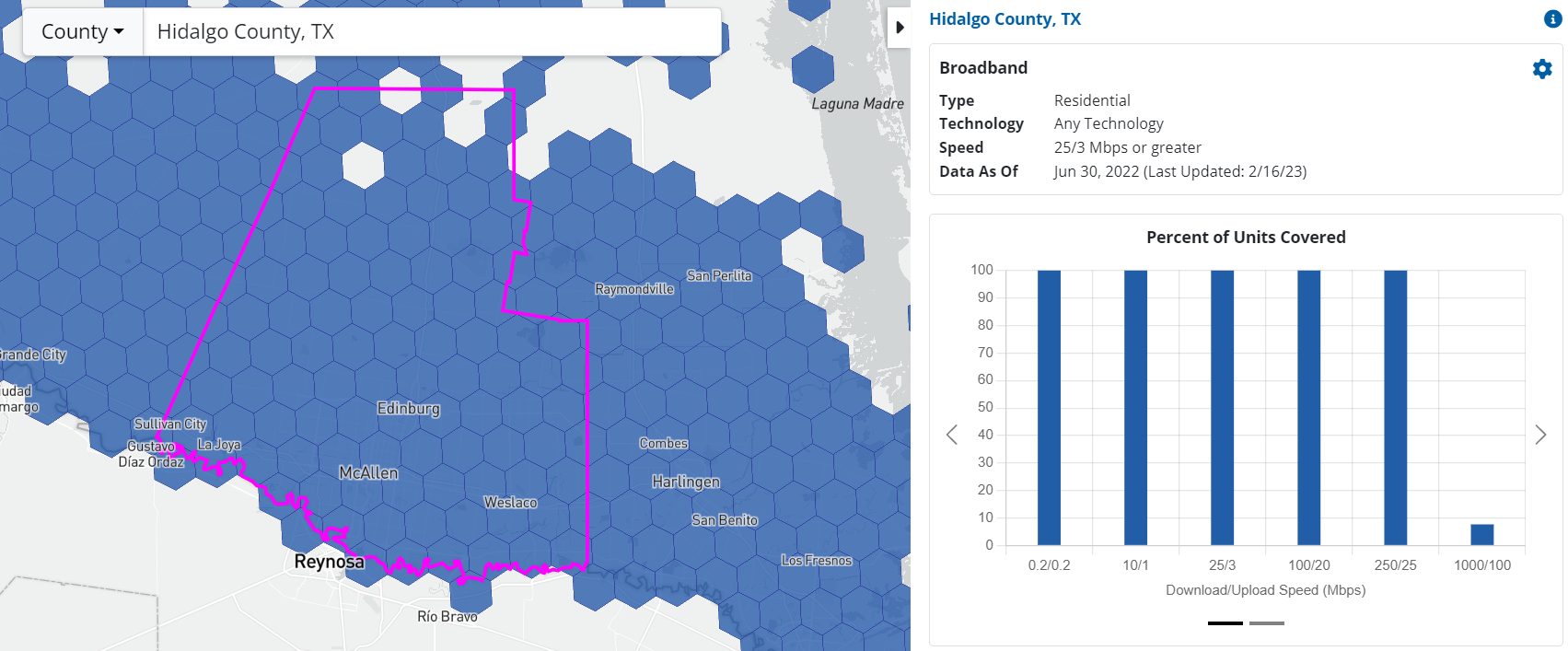

While plans may be costly for low-income families and the internet connection frequently disrupted, the Federal Communications Commission does not consider communities like Donna or Salineño as underserved areas in their latest broadband maps unveiled in November 2022.

“By painting a more accurate picture of where broadband is and is not, local, state, and federal partners can better work together to ensure no one is left on the wrong side of the digital divide,” Jessica Rosenworcel, the FCC’s chairwoman, said at the time.

As part of the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in 2021, the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program, or BEAD, received $42.45 billion to be distributed by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, or NTIA, for expanding internet access in the U.S.

Each state will receive a minimum of $100 million, while the remaining money would be allocated based on NTIA’s formula considering the number of unserved and high-cost locations in the state. This is based on the updated broadband availability maps published by the FCC, according to a notice shared by the agency last year.

States will need to submit a five-year action plan to the NTIA no later than 270 days after receiving planning funds. Using a formula based on the FCC maps, NTIA will notify each state of their budgets by June 30. States can submit an initial proposal as soon as they’re notified of their budgets or up to 180 days after the notification. Once NTIA approves the initial plan, or no later than 365 days after, the states can submit a final proposal for NTIA approval and unlock the first 20% of their funding for broadband projects.

Those federal funds will be trusted to the Texas Office of the Comptroller of Public Accounts, which houses the Broadband Development Office. They will determine based on information they receive from regions how to distribute the money.

When the FCC unveiled their maps of broadband coverage, Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar expressed disapproval.

“This is clearly a flawed map,” Hegar said in December 2022.

Hegar, among others, including advocates and public officials, believe the maps used to distribute the money are inaccurate and could lead to funding disparity.

When we reviewed those FCC maps of high speed broadband internet coverage, we were surprised that the majority of Hidalgo County showed us having access to broadband,” Isaac Sulemana, the chief of staff for the Hidalgo County judge’s office, said.

Hidalgo County invested millions into a Wi-Fi expansion project during the pandemic.

“Based on our experience with the Wi-Fi expansion, we didn’t feel that that was accurate,” Sulemana said.

Cameron County was similarly dissatisfied with the map’s accuracy and created a community survey to collect their own data.

Although the FCC granted a period to challenge the maps, the deadline approached faster than some governmental entities could respond.

“States and stakeholders need additional time to submit challenges to the proposed national map to provide critical, accurate information on the availability of broadband in their communities,” Hegar added. “This will ensure every dollar is fairly allocated using the most reliable data.”

Hegar and Cameron County on Dec. 13 sent NTIA a request for a 60-day extension for challenging the maps, but the request was unsuccessful.

In spite of that, some governmental entities still plan to challenge the FCC maps.

THE FCC MAPS

The FCC maps collected information from ISPs through a third-party contractor that gathered information for fixed broadband and mobile broadband.

Fixed broadband includes fiber, cable, DSL, satellite, or fixed wireless internet services available at each home or small business on the map.

Mobile broadband shows the 3G, 4G and 5G coverage of each mobile provider for the area displayed. Hot spots connect to the same mobile networks.

According to the FCC, the coverage areas reflect where consumers should be able to connect to the mobile network when outdoors or in a moving vehicle, but not indoors. The map allows consumers to compare mobile wireless coverage reported by different mobile providers.

The FCC maps indicate that the areas where the Salineño and Donna families live are covered 100% by fixed and wireless broadband with a download speed 25 megabits per second, or mbps, and an upload speed of 3 mbps.

CONCERNS

Among the voices leading the discourse questioning the maps was Jordana Barton-Garcia, a South Texas native with experience in finance, economic development, broadband expansion and digital inclusion.

“We’re really talking about people,” Barton-Garcia said last month after authoring a letter to the Lower Rio Grande Valley Development Council. “What do people need to thrive?”

Barton-Garcia works as the senior fellow for Connect Humanity, a fund for digital equity employing a holistic approach by focusing on infrastructure, policy, affordability, content and digital skills.

In her letter, Barton-Garcia explained disadvantages in the FCC maps to the LRGVDC.

A key concern was the definition of underserved and unserved areas.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act defined unserved locations as those with either no broadband access or broadband service with speeds up to 25 megabits per second for download and 3 mbps for uploads.

These unserved locations will receive funding priority. The second tier for priority funding are regions considered underserved with internet download speeds of up to 100 mbps and 20 mbps for uploads.

Problems arose when Barton-Garcia looked at the data reported for South Texas.

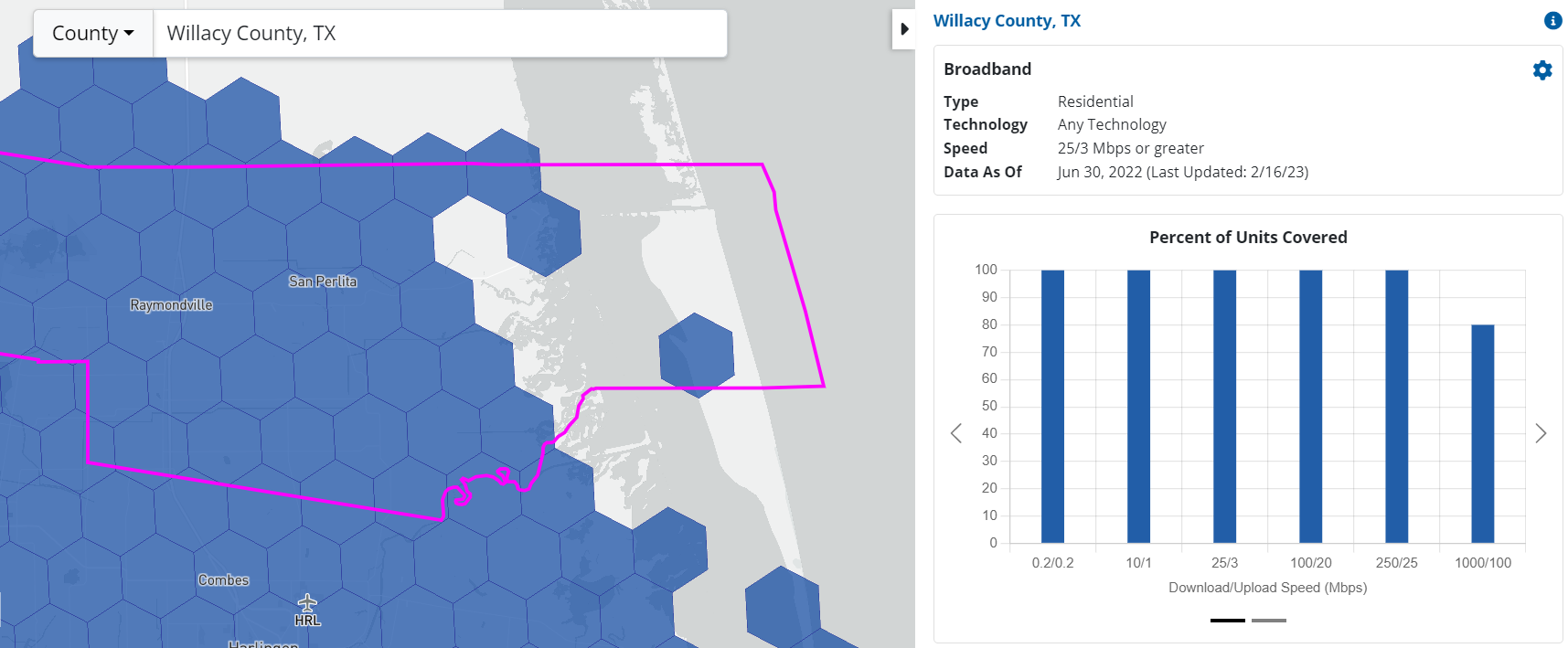

The whole Valley — Starr, Hidalgo, Cameron and Willacy counties — was ineligible for priority funding; the maps reported 100% of the Valley is served with internet speeds ranging from 25/3 mbps, to 100/20 mbps, and 250/25 mbps.

“Generally speaking, ‘access’ for the FCC means an ISP can provide (within 10 days) broadband service of a minimum speed of 25/3 mbps to a residential or commercial address using any technology, irrespective of whether such speed is sufficient for consumer needs,” Barton-Garcia wrote. “Nor does it account for the potential cost of a line extension (which could cost a consumer thousands of dollars to install); the monthly subscription price; the cost to own or rent premise equipment, such as a cable modem, wireless router, or satellite dish; nor the cost of connectivity devices, such as a desktop computer, laptop computer, tablet, or wireless phone.”

Another point of contention was the FCC maps’ exclusion of affordability. Families in the Valley who struggle with low wages experience financial barriers to internet access, a factor excluded from infrastructure maps.

Residents living in rural or remote areas may be too out of the way for fiber or cable internet, but options are available. Though, prices can vary. Some internet service providers waive the installation fees while some, like Starlink, charge a one-time installation fee of $600.

But Barton-Garcia stressed the importance to consider both, infrastructure expansion and extra consideration of persistent poverty regions, like the Valley, when planning funding distribution.

The view is more than opinion. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act instructed the funding to be prioritized in historically disadvantaged communities, high-poverty areas, and persistent poverty counties.

“You create win-wins when you don’t run on a scarcity mentality,” Barton-Garcia said.

One of the conclusions of the letter was to spur the Valley to request that NTIA waive their reliance on the new FCC maps for determining funding for the area.

Otherwise, Barton-Garcia admonished, residents earning low incomes could continue to suffer the consequences of the digital inequity including access to education and health care, namely telehealth.

FAVORED TECHNOLOGY

Internet service providers, like VTX1 based in Raymondville, are part of the dialogue to help determine the best course of expansion.

Over in their Willacy County offices, VTX1, which started as a telecommunications cooperative and pivoted to internet service in the early 2000s, is preparing for the future.

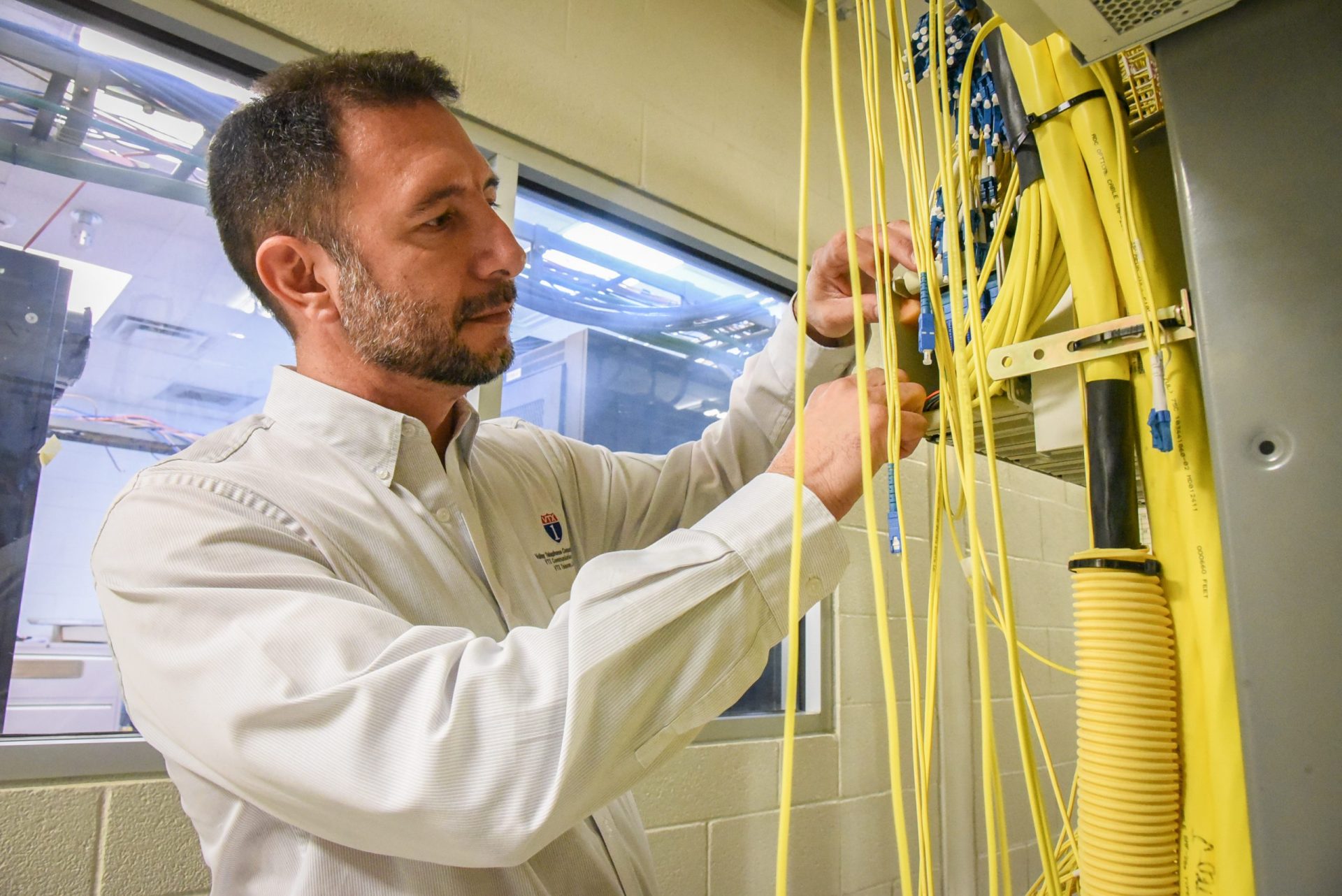

One of their warehouses is filled with the technology and equipment needed for cities, counties, and states to expand broadband.

Spools about 6 feet high wrapped with black cables and green plastic utility boxes fill the warehouse parking lots while, inside, the rest of the components of fiber optic internet sit patiently waiting for deployment.

Sebastian Ivanisky, VTX1’s chief technology officer and employee for 19 years, said they began ordering as much supply as they could when the pandemic began stressing the need for internet access and the demand created shortages around the world.

Now, they have about 1,200 miles of fiber in stock, a part of $30 million worth of fiber and equipment acquired for future projects.

Fiber optic internet is a favored technology by customers.

Unlike other forms of internet delivery, information runs fastest through fiber optic cables. The innermost part of the fiber cables that are either buried 8 feet underground or hung on utility poles are made of glass and protected by multiple layers of plastic. The glass allows VTX1 to deliver information at download speeds of 1 gigabit, or 1,000 megabits, per second.

Other companies that offer fiber may have some limitations that VTX1 does not have, Ivanisky explained one afternoon as he sat with a sample of a fiber cable on his desk.

VTX1 will take the fiber from the ground and into the home through a small wire that connects with equipment inside the residence or business. Some providers will connect their fiber optic cable to customers using existing coaxial cables, the same used for cable TV, which use copper and have a hardwired limit.

Theoretically, Ivanisky said, the delivery speed of fiber optic cable is so high experts disagree on its limit.

While many think greater speeds are best, VTX1 is not banking on it. Ivanisky said the typical internet user averages about 4 megabits per second, far from the lowest plan they offer of 100 mbps.

So, when lawmakers and public officials ask him whether the future is fiber, he always responds in the same way.

“We’re technology agnostic,” Ivanisky said.

While fiber is fast, it’s costly.

The average cost for the deployment of a mile of fiber is between $50,000 and $60,000.

VTX1 currently has about 6,000 miles of fiber stretched all throughout South Texas and running up through San Antonio. Altogether they have about 7,000 customers.

But they have more than 20,000 customers who opt for another form of technology using 300 tower sites: fixed wireless broadband.

“So with the newer technologies [fixed wireless internet] that we’re in right now, we’re offering up to 400 megabits with the latest stuff that we’re deploying now,” Ivanisky explained.

Fixed wireless works mostly by installing a small panel of equipment, which functions as an antenna, to the customer’s residence or business and pointing it in the direction of a tower transmitting a high-speed internet signal that can deliver speeds of up to 400 mbps.

Recently, VTX1 began upgrading their fixed wireless equipment and purchased Tarana G1, what the manufacturer calls next generation fixed wireless access. It shrunk the technology used to send the high-speed internet signal from towers while expanding the signal’s radius.

The equipment and installation of fixed wireless technology is more cost-effective than fiber.

Ivanisky explained that costly fiber installation is not economically feasible in areas where only a handful of potential customers exist. Even with federal funding, customers would still need to pay for the service which would be more affordable if fixed wireless internet technology was deployed.

Politicians focused on fiber might also be dissuaded by time.

I would ask a politician that firmly believes that fiber is the only answer,” Ivanisky said, adding, “to go to a mother and tell her we’re going to get the broadband you need to educate your children. We’re going to get it for you, and it’s going to be free. But it’s going to be in five years when he should be graduating, not now when he’s supposed to be enrolling.

FUTURE PLANS

Local governments are taking action to fight for more funding, but they first have to find data justifying their argument to receive priority.

In Cameron County, residents were asked to participate in a survey to collect internet speed data that could provide another source of information to clarify the regions’ internet access.

The information they’ve gathered will be used to partner with ISPs and to request grants from the federal government, according to county officials who spoke before the commissioners court Tuesday.

Consultants they hired to analyze collected data said they estimate it would take up to $17 million to build a fiber network covering 178 miles. And it would take about $100 million to connect everyone living in the area to fiber optic internet. They noted, however, that it’s an overestimate of what the final cost could be to err on the side of caution.

Hidalgo County will also be conducting a broadband feasibility study, the judge’s office chief of staff told The Monitor.

“The intent would be to now have our own data from the ground level that is not based or that’s not coming from the [internet] service providers,” Sulemana said. “We’re now having to take an affirmative step to determine what their coverage was, so that we have something to present in our request for additional funding and additional coverage.”

Once the data is collected, Sulemana said he hopes it will help increase the county’s eligibility for additional funding.

Cameron County’s consultants said they don’t believe the BEAD program funding will be available until early 2024.

As the federal government prepares to release funds, local governments in the Valley will continue preparing to make a case for increased funding and decide on which technologies to invest in.

The FCC maps will be updated periodically, even after the states are notified of their budgets on June 30. Data collected by local governments, nonprofit organizations, and broadband service providers will influence the updated maps in the future and help state governments, who are funneling funds, to determine where the money ends up.

ISPs like VTX1 are working on improving their internet speeds, too.

Ivanisky explained they aim to provide a minimum of download and upload speeds of 100 mbps. Most providers are aiming for 100 mbps speeds, because they don’t want a competitor to be funded in their territories. Hitting that mark will also help them be attractive when the public sector is looking for partners to expand broadband.

The goal is shared with advocates like Jordana Barton-Garcia who supports Jonathan Sallet, an FCC policy consultant who authored Broadband for America’s Future that called for a minimum of 100 mbps symmetrical speeds for households, though he opted for a fiber-based network.

While data gathering by local governments will help determine need and whether a combination of broadband technologies will be more economically feasible, efforts are poised to produce positive progress.

“If we disregard our knowledge of the speed and capacity that are needed now and in the future,” Barton-Garcia wrote, “we will be perpetuating the digital divide.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the amount of tower sites and download speeds.