By Shannon Najmabadi, Texas Tribune

Texas hospitals are suing patients for unpaid medical bills, a practice that has continued even as the coronavirus pandemic sends unemployment skyrocketing and spurred the state Supreme Court to pause debt collections and eviction proceedings earlier this year.

Hundreds of debt collection lawsuits have been filed since Gov. Greg Abbott declared a state of disaster because of COVID-19 in mid-March, including more than 345 suits brought by facilities associated with one Tennessee-based company, Community Health Systems Inc., according to the Health Care Research and Policy Team at Johns Hopkins University.

While district clerks’ offices confirmed medical debt lawsuits have been filed recently, other proceedings have been paused, including default judgments, which hand wins to medical facilities if patients don’t respond. Those were allowed to resume this month, and debt collectors were permitted to restart garnishing bank accounts on cases that have been decided. Accounts frozen before the Supreme Court’s April order were not affected.

Advocates fear the resumption of debt collection could push Texans, already battered by the pandemic’s economic blows, into dire financial straits. More than 1.9 million people have filed for unemployment relief in Texas in the last two months.

“I’d say, fast forward a year from now, regrettably or not, we’ll see a ton of bankruptcy,” said Dana Karni, an attorney for Lone Star Legal Aid, which provides free legal services to low-income Texans. With lack of income and mounting bills on cars, medical visits and other expenses, “I don’t see how consumers can come out from all the debt.”

The Johns Hopkins research team combed through court records and interviewed patients sued for unpaid medical bills in 62 Texas counties — concentrating on the two years between January 2018 and February 2020. Their findings, which were released Wednesday, shed light on what medical facilities have filed lawsuits in Texas, though it’s unclear if the pandemic, which has decimated many hospitals’ revenue, will change those patterns.

“Hospitals are under greater financial strain now … during the pandemic than before, because a lot of their profitable services and their more revenue-generating services are not happening,” said Erin Fuse Brown, a law professor at Georgia State University whose work focuses on health care costs. “It’ll be interesting to see whether or not that increases the pressure on hospitals to seek collection from patients.”

The researchers’ findings show that 28 of 414 examined hospitals sued Texas patients between 2018 and 2020, generally recovering negligible portions of each medical facility’s revenue but financially crippling some patients. A handful of the hospitals — six of which are based out of state — garnished bank accounts and seized indebted patients’ property after winning their suits, the researchers found. The hospitals sued for over $17.8 million in medical debts, with average lawsuits ranging from about $4,000 to $40,000, the report found.

Many of the sued patients lived in counties with median household incomes below the national average, and in nearly half of the cases, patients didn’t appear in court — leaving the medical facility with a default victory, the researchers found. They focused on counties they thought had the most cases and where online court records were available.

Carrie Williams, a Texas Hospital Association spokesperson, said in an email that hospitals are “in the business of taking care of people and much prefer to work closely with patients and payors … to settle account balances in a way that works for everyone.” This could include self-pay discounts and other payment programs, though Williams said “they may take more significant action to recoup certain costs as a last resort.”

“Sometimes those costs are deductibles or the cost of services rendered that their insurance coverage does not or will not pay for,” Williams said.

Hospitals are required by Texas statute to bill a patient’s insurer first.

Hospitals struggling

The research comes as hospitals across the country have been scrutinized for suing patients, sometimes even their own employees, for unpaid medical bills. Nonprofit hospitals are required to offer free or discounted care to low-income patients in order to keep their tax-exempt status. But news reports have found some send medical bills to patients likely to qualify for the charity care, and they can rely on aggressive collection tactics if payments aren’t made.

The research team found the majority of the medical debt lawsuits between 2018 and 2020 were brought by hospitals, which sued in more than 1,000 cases in Texas. The most prolific filers were for-profits, and several are affiliated with Community Health Systems, one of the largest health systems in the country, the report found.

Hospital representatives said litigation is used as a last resort, pursued only when the facility believes the patient has an ability to pay, based on their employment status or credit record, and after numerous attempts to contact them have been made.

“We offer charity care, discounts and extremely low, long-term payment plans that are often less than $25 per month,” said Bo Beaudry, chief executive officer for Cedar Park Regional Medical Center, adding the facility isn’t pursuing suits against people who have lost their job due to the pandemic. “Collecting reimbursement for the care we provide is critical to sustain operations and continued investments to enhance care for the community.”

Radiology imaging and diagnostic centers also filed lawsuits — about 5% of those examined in the two-year period, or 58 cases. Outpatient clinics brought 3.4%, or 38, of them.

Many hospitals are under immense financial pressure because of the outbreak.

Moody’s Investors Service changed the not-for-profit and public health care sector’s outlook to negative in March “primarily driven by the effects of the coronavirus outbreak.”

The federal government is giving health care facilities money to help cover the cost of treating uninsured people with the virus and to make up for revenue lost when lucrative elective procedures were canceled for a potential surge in COVID-19 patients.

Marty Makary, a surgeon and professor at Johns Hopkins and senior author of the study, said that “COVID relief funding should be conditional on a hospital having fair and honest billing practices.”

Patient protections

Texas has some protections in place for patients.

The state is one of four that bars debt collectors from garnishing any wages, and homeowners can’t have their houses sold out from under them to pay off medical debt. Cars and retirement accounts generally can’t be seized either, though liens can be placed on certain properties, like second homes.

“Those are really important protections, and many states don’t have that,” said Ann Baddour, director of the Fair Financial Services Project at Texas Appleseed. Still, “the one thing that we’re missing is a cash protection. … A debt collector can’t go to an employer and garnish the wages from the employer. But once the wages are deposited in a bank account, they’re fair game.” Other states set limits on how much money can be taken out of a person’s account.

The specter of those repercussions can push patients to settle.

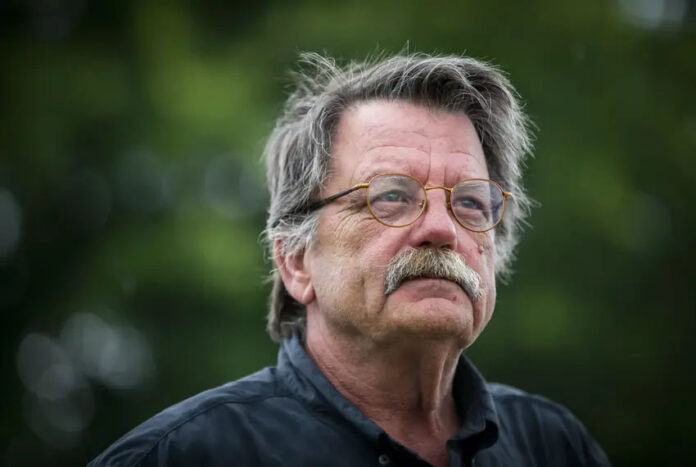

Take Patrick Easley, a civil engineering construction inspector outside Houston. He has worked almost all his life — starting in land surveying right out of high school and staying for about 25 years until he was laid off during the 2009 recession. After that, he hustled to work nights and weekends at Home Depot and as a laborer, but he hasn’t had health insurance since then, he said.

Premiums and medical costs have become too expensive since the Affordable Care Act was passed, said Easley, 62.

Court records show he was ordered last year to pay $16,196.02 in medical debt, 5.5% interest and a $3,000 attorney’s fee, after a Tomball hospital treated his wife, who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he said.

He hired a lawyer for $300 as soon as he received the lawsuit but was told there was little chance to negotiate the amount down.

“Either pay up or they’ll put a lien against [all your assets],” he remembered. “I was like, ‘I’m against a wall. I’ve got to do what I’ve got to do.’” Easley swiftly agreed to pay what he could afford — about $125 a month.

“I’ll be paying until I die,” he said.

The U.S. pays more for health care than other high-income countries, and employer-based health insurance premiums and deductibles have increased significantly.

One in four Texas households have medical debt that is being collected on, according to a 2019 report from Every Texan, a left-leaning think tank formerly called the Center for Public Policy Priorities. In neighborhoods where most residents are people of color, the number was closer to one in three.

Fuse Brown, the Georgia State professor, said hospitals turn unpaid medical bills over to debt collectors or file lawsuits when “they’re trying to recoup some of that money.”

“The downside, of course, is that for the patient, a $1,000 bill … particularly compounded with interest, could be the difference between being able to put food on the table or pay their rent.”

For higher amounts, it could lead to bankruptcy, foreclosure or a person being “tipped over into financial ruin,” she said.

Most of the Texas lawsuits were filed by the DeLoney Law Group PLLC, which brought the overwhelming majority of the medical debt suits reviewed by the researchers.

Chris DeLoney declined to respond, saying that “we don’t comment on any matters that may relate to any of our clients.”

The other lawyer identified in the report, William Franklin, represents the University Medical Center in Lubbock, the primary teaching hospital for Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

He said the firm has filed 94 lawsuits on behalf of the medical center since January 2018 that involved patients — about two dozen of which were “settled amicably” or dismissed when more information was learned about the patients’ financial situation. Five additional cases were settled with payment plans as low as $50 a month, Franklin said.

The center did not garnish any patients’ accounts, and it has requested writs of execution be issued but not seized property through the process since January 2018, he said.