BY NORMAN ROZEFF

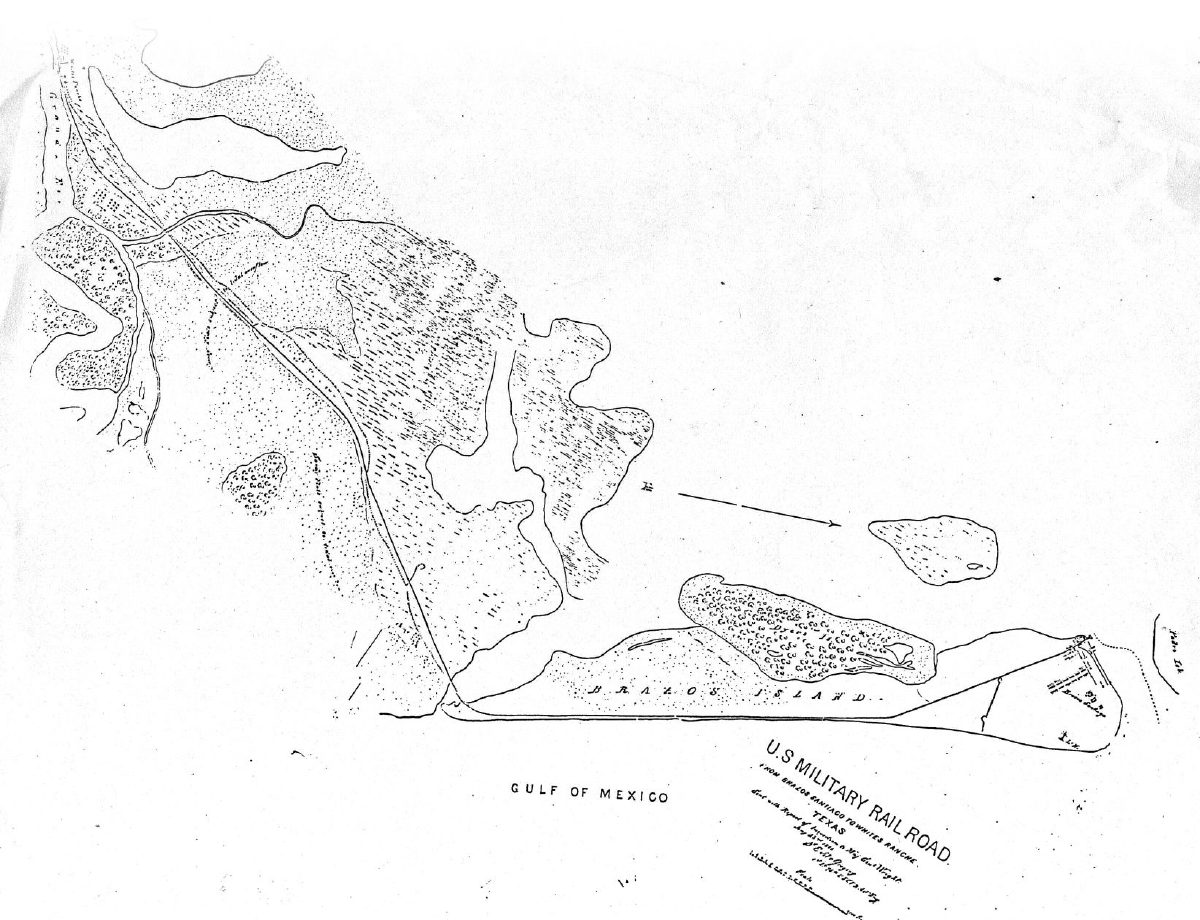

An early survey of the pass and bay was made between January and March 1871, and seven years later Congress appropriated $6,000 to remove a wrecked French vessel from the pass. Between 1878 and 1889 seven appropriations totaling $253,500 were made for harbor improvements, but not all was spent.

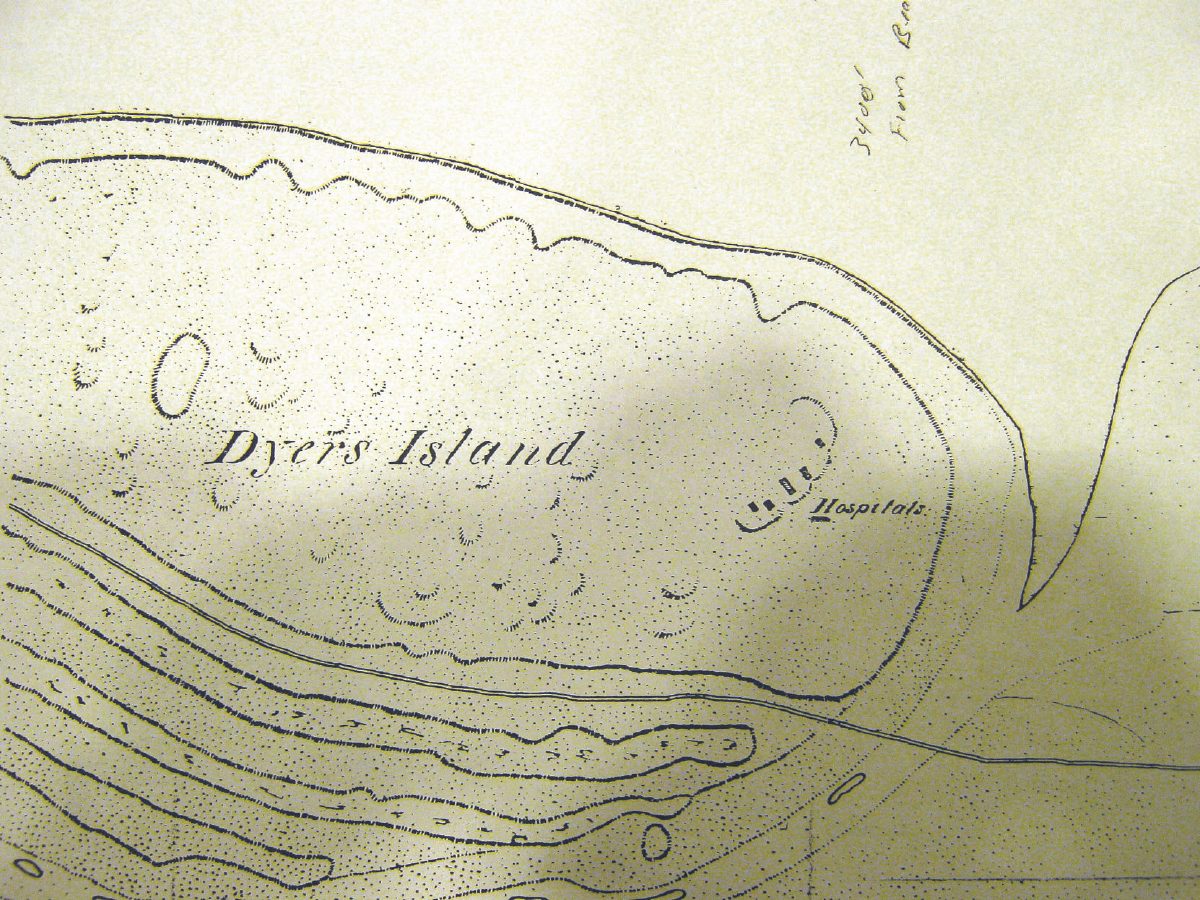

Of interest is the Brazos Pass Quarantine Station that was built in 1880.

Since the very contagious disease of Yellow Fever was common among sailors from on foreign ports, the station was deemed a necessary precaution.

The building was abandoned in 1908 but was then utilized by vacationing individuals from the area. It was demolished after the 1933 hurricane made it a hazard for occupants.

The U. S. Life-saving Service (later combined with the Revenue Cutter Service in 1915 to form the U. S. Coast Guard) Station was situated on Brazos Island facing the pass. It had been constructed from parts salvaged from the original station that had been heavily damaged in the storm of 1912.

It was then abandoned in 1922 for a new site near the south tip of Padre Island. The Labor Day Hurricane of 1933 destroyed this building.

Important to the financial success of the area was the ocean commerce that for decades was the only available export-import outlet for the region.

While the shallow Pass of Brazos Santiago was always a hazard to shipping, the construction of the lighthouses aided navigation. Original light was a movable wood structure with wheels.

The first tower was built in 1864. It was constructed of wood and was 30 feet in height but in the same year the tower was rebuilt and four feet was added to its height.

The keeper’s wife was killed and the tower destroyed during the 1874 hurricane. The tower was rebuilt in 1879 as a wooden cottage-style hexagonal screw-pile structure.

By 1903 the light had reached 60 feet and had a fourth order Fresnel lens. It burned down in 1940 and by 1943 the light was placed on the Coast Guard building at the south end of Padre Island.

In 1930 Colonel Sam Robinson received Brazos Island, located at the mouth of the Rio Grande River, and the Boca Chica toll bridge as payment for a debt. He devoted the remainder of his life to the development of his seaside resort, Del Mar.

The two 1933 hurricanes greatly damaged this Robertson project, one that had advanced more than the Ocean Beach Driveway. His Del Mar beach resort was on the south end of Brazos Island. Here he had constructed thirty-one modern cottages, a bath house, a restaurant, and a hotel building named the “Surfside”. August 1931 saw a channel opened from Del Mar to the Laguna Madre. Some thoughts were to dredge a channel from Del Mar to Brownsville, but this never came to pass.

By February 22, 1922, however, a road from Brownsville to Del Mar had been completed. On 10/12/32 the telephone line that took the Rio Grande Valley Telephone Company 35 days to erect reached the Del Mar project.

When the resort reopened in April 1934 there were 26 new cottages advertised as having the latest amenities “including private shower and bath, and a telephone in every room.”

These were constructed more sturdily than the previous ones and were bolted to a deeper foundation as well as having re-enforced walls and roofs.

Years later some of the cottages were eventually moved to Harlingen where they were transformed into cabins for a motor court on South F Street. They are there to this day. A new restaurant and dance hall were also built and the old bathhouse repaired.

While Maria (Robertson’s wife), Sam and family friends, Mr. & Mrs. Neil Hanson and Mr. & Mrs. Henry Hicks rode out the first storm at the resort, Sam and Maria were fortunate that they decided to go inland when the Labor Day Storm of 1933 hit the area with wind gusts up to 125 miles per hour.

By April 7, 1934 the Robertsons reopened after repairs and the addition of an asphalt road and toll bridge from the Boca Chica Pass to the resort.

The Labor Day Hurricane of 1933 was immense in its negative significance to the Valley.

Until the year 2005, the year 1933 held the dubious honor of recording the most hurricanes to occur in the Atlantic Ocean. In that year the twenty-one storms which arose were not yet given names.

The Labor Day storm which was to hit the Lower Rio Grande Valley was simply Hurricane # 11, 1933. On July 22 the area had been swiped by a tropical storm south of Matamoros near Tampico. On August 4 a minimal storm whipped Brownsville. With winds of 75-80 mph it caused $75,000 damage in Brownsville.

To qualify as a hurricane sustained winds must average 74 to 100 mph. A tropical cyclone with winds of 101 to 135 mph is categorized as a major hurricane and with winds of 136 mph or more an extreme hurricane. The odds of a tropical storm or a hurricane striking the area from the mouth of the Rio Grande to the south edge of Baffin Bay in any one year are 1 in 7.

From David Roth of the Lake Charles Weather Bureau office who compiled Texas Hurricane History: Early 20th Century we learn that before August 28, 1933 a depression had formed and strengthened in the Atlantic Ocean east of the Bahama Islands.

Passing ships and boats had alerted the U. S. Weather Bureau to the storm, so it was tracked from its inception until landfall. On August 30 it passed over Turks Island in the Bahamas and registered the very low barometric pressure of 27.47”, a compelling indication of its intensity. It advanced towards Cuba and with 94 mph winds struck Havana in the late afternoon of September 1. Seventy-five miles east of Havana, the north coast city of Cardenas, Cuba, famed for its Havana Rum, saw the storm kill 30 people and injure more than 100.

The ferocity of the storm ruined its piers and caused millions of dollars in damages not only to the waterfront and boats, but also to its sugar cane factory and distillery. A large red harbor buoy was deposited inland into a city park by the tidal surge. It was later mounted on a foundation and remains to this day as a reminder of the fateful storm.

The Valley was not unaware of this storm, for one of the two first page headlines of the Valley Morning Star of 9/2 read “Tropical Storm Strikes Havana, Injuring 16 Persons” with the sub-headline “Six Reported Killed and Damage Mounts.”

The following day the headlines proclaimed “Hurricane Loss 60 Dead in Cuba”.

As it proceeded westward the movement of the hurricane’s eye averaged out to just under 10 mph. Once on the same latitude as Brownsville it turned west. On the Labor Day weekend and September 4 the impending storm made known its presence with increased wind velocities. The next day it made landfall on South Padre Island, just north of Brownsville.

In a quirk so common with tropical storms, its heretofore westerly course now changed into a slightly southwest path. This brought the eye of the storm directly over San Benito and Harlingen. An imaginative, but totally erroneous map, of the hurricane’s track was published in the VMS 9/9 paper.

It showed the eye coming ashore at Freeport then following the coastline inshore all the way to the Valley before turning west.