Peña wrote of her fear that in the wake of the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance immigration policy, children would be deported to Central America without their parents, “stranded, vulnerable and at grave risk for human trafficking.”

“I thought that when I wrote it I might be a little dramatic when I said that children would be arriving to Guatemala City alone,” Peña said in a Sept. 6 interview. “I basically wrote the worst-case scenario in my mind, and it’s even worse than the worst-case scenario.”

As the Trump administration works to build a physical wall along the nation’s southwest border, it has simultaneously leveraged executive orders and policy adjustments to create an invisible wall. Since U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ April 6 announcement that anyone who crosses the border illegally will be prosecuted, the government has ruled that people fleeing domestic or gang violence do not qualify for asylum and has urged the end of time limits on detaining migrant children.

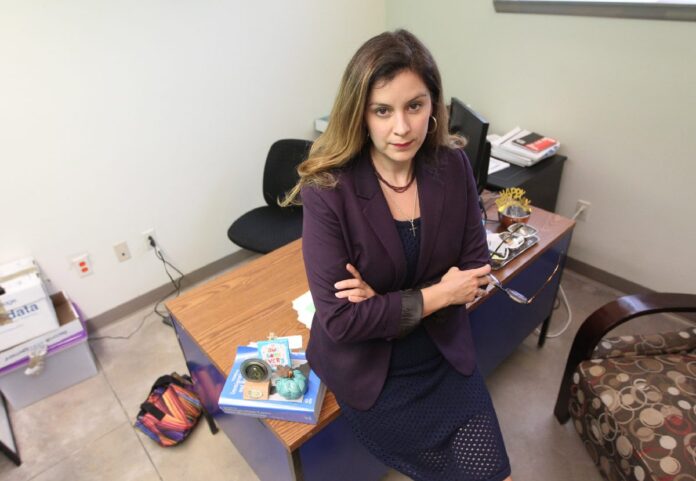

A former assistant chief counsel at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement under the Obama administration, Peña left her job as a business immigration attorney in California in May and has worked as a visiting attorney with the Alamo-based Texas Civil Rights Project since July.

“I felt called to come do this work,” she said. “I knew that I was going to come home and help these families and I didn’t know how or with who; I just knew I was going to do this work.”

She saw a video of TCRP’s Racial and Economic Justice Program Director Efrén Olivares speaking outside the Ursula Border Patrol Processing Center in McAllen and reached out to him about volunteer opportunities. As fate would have it, he received her email two hours after the organization decided it needed to hire a visiting attorney with immigration experience to develop and manage strategies to assist with family reunification.

TCRP has provided and coordinated pro bono representation for approximately 400 of the 2,500 families separated after crossing through the Rio Grande Valley in the spring and summer. As of mid-September, about 10 of these families remain separated, held in detention centers in Port Isabel and Willacy County as well as facilities in California and on the East Coast. Nationwide, 500 migrant children remain separated from their parents. Some parents have been deported, while others remain in detention centers because their cases are still being vetted or they have been deemed ineligible to immediately regain custody.

“This last group of remaining families arguably are subjected to the most trauma because the length of time of the separation is just increasing, so they’re not eating, they’re increasingly depressed (and) starting to give up hope,” Peña said. “They all keep me up at night. They’re all tough cases and it’s like fighting them tooth and nail.”

She spends much of her day on the phone, taking calls from detained parents, advising the pro bono attorneys TCRP’s staff is working with and requesting information from the federal government. She visits clients at local detention centers and goes to McAllen’s federal courthouse on a weekly basis to interview migrants being prosecuted for illegal entry, screening for any family separations.

Despite Trump’s June executive order ending family separations, the zero-tolerance policy is still in effect. Some days, 50 people are prosecuted for illegal entry at the federal courthouses, while other days the number exceeds 100.

“I try to keep the advice that I give our clients, which is paso a paso, step by step,” Peña said. “Whatever is in front of you, you have a goal, that immediate step, that immediate action. You have to take it in bite-size chunks, otherwise it’s so overwhelming.”

It didn’t always look like this.

Peña joined ICE as a trial attorney in 2014 to learn about the U.S. immigration system from the inside, working in federal courtrooms in Los Angeles and San Diego until March 2016. She came on during the height of the 2014 immigration crisis when a surge of unaccompanied children from Central America attempted to enter the U.S., fleeing countries like El Salvador and Honduras that were ravaged by gang violence.

“The difference is that this was a manufactured crisis,” Peña said of the crisis immigration attorneys currently face. “This was a crisis of our government’s own making, which really infuriated me, having seen a true humanitarian crisis and having been with the government during that time.”

Just a few years before, as a senior advisor at the U.S. Department of State under Secretary Hillary Clinton, Peña worked on citizen security, democracy and human rights issues in Latin America.

ICE trial attorneys had considerable prosecutorial discretion under Obama to determine whether or not an individual was a priority for removal. The highest priority group for deportation did not include children and families who entered the country illegally, but rather serious criminal offenders deemed a national security threat.

“As an ICE trial attorney, I didn’t believe in winning and losing,” Peña said. “I believed if relief is available then it’s the government’s job to see that the relief is rendered.

“Immigration law is administrative law, but my takeaway after being an ICE trial attorney is that the immigration system has been criminalized,” she said. “It has such a law enforcement focus that the trial attorneys in the courtroom are emboldened to take a prosecutorial stance depending on who is in the White House.”

Peña plans to work at TCRP through the end of the year. The next chapter of her career remains to be seen.

“I’ve been all over the world, and right now this is exactly where I’m supposed to be,” she said. “After this, who knows. I have no idea, which is exciting.”