BY NORMAN ROZEFF

The movement of General Taylor’s Mexican-American war supplies began in October 1846 with the quartermaster corps bringing in Captain Mark Sterling of Pittsburgh to command the riverboat, the Major Brown.

Logistically there were challenges. Fluctuating river levels along the course to be taken were problematic as was the inability of mesquite logs being burned to generate enough steam. Unchar- ted sand and gravel shoals in the river were an additional problem.

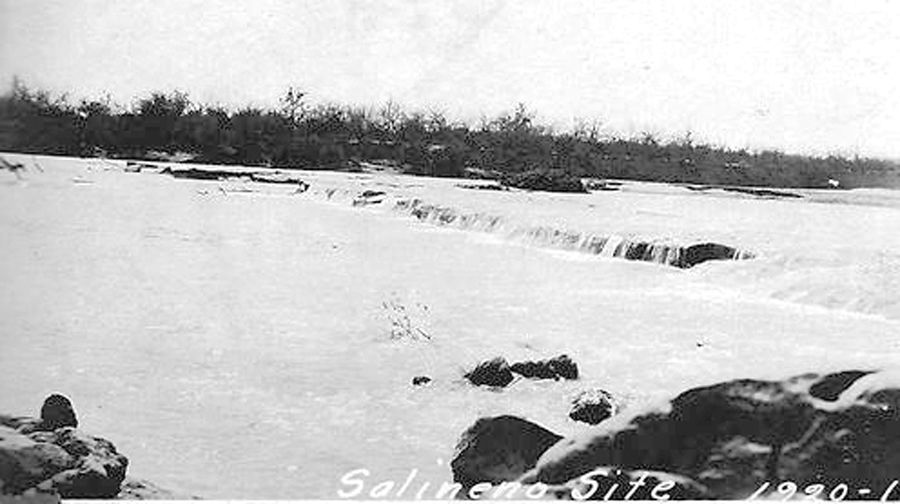

A ledge that spanned directly across the river above where the Salado joined the Rio Grande was yet another obstacle.

This ledge would later restrict passage of steam boats to reach Laredo. In short, over time, Roma, 30 miles above Camargo, would be the farthest that steam boats could safely traverse upstream from Brownsville.

The Major Brown was to accomplish a feat that was never matched again. This steamboat was a 125 ton sidewheeler, 150 feet long, having a beam of 46 feet and a draft fully loaded of only three feet. After the Battle of Monterrey, General Taylor wished to explore further up the river with a mind to possibly supply the military at Presidio de Rio Grande.

The Major Brown commenced its exploration on October 1, 1846. The steamer was able to reach the mouth of the Salado from which it was 12 miles on that river to the town of Revilla/Guerrera.

At this point the sparsely vegetated banks rose sharply, but it was the Guerrera Falls on the right of a large island in the center of the river that gave pause.

While the Rio Grande was reported to be in a low stage, the Salado was full, so the sidewheeler advanced to Guerrera where it received a warm reception. The steamer was able to find hard bituminous fuel in the neighborhood before departing on October 8.

Once again at the mouth of the Salado, the crew of the Major Brown, set out to sound the river that now offered numerous impediments to further travel upstream.

On the left was found a depth of 5 ½ feet, but the entrance was closed by a bar of sand and gravel. On the right was sufficient water, but points of rock arose from the bed.

Upon discovering this situation an advance party of 20 was sent ahead to investigate the situation maintaining in the river above. It reported back that the river beyond was more friendly and would be even more so once its level came up.

The boat, with utmost caution by her crew, transited the dangerous obstacles. Twenty miles more she encountered a reef extending diagonally across the river and extending one mile in extent. In some places on this reef the water fell two feet.

Fortunately, nearer the American shore, there was a passage of 100 feet enabling the vessel to proceed despite the rapid flow of water through it. Just beyond this point, however, the craft nearly met disaster as power was lost, and the boat swung dangerously close to two rocks.

Quick reactions by Captains Sterling and McGowan saved the day. Progress was slowed as more reefs were encountered, but on October 24 Laredo was reached, much to the astonishments of its inhabitants.

The fall in the river level then put advancing to Presido de Rio Grande out of the question. Never again would a steamboat traverse the whole of the river to Laredo.

The war requirements taxing the river brought some well-known Valley figures to the fore. Mifflin Kenedy, who at an early age had become a sailor and the acting captain on steamboats, was first recruited to bring military supplies from New Orleans to the Valley on the steamer The Corvette.

Kenedy enticed Richard King, who himself had steamboat experience at an early age, to join him in the war effort in the Valley. King then worked on the Colonel Cross ferrying army supplies between Camargo, Reynosa, and Matamoros.

As Wikipedia tells us “In 1850, following the war, King, Kenedy and two other partners formed the M. Kenedy and Company steamboat firm, renamed in 1866 to King, Kenedy and Company when the two other partners were bought out.

This firm achieved “nearly monopolistic” control on the Rio Grande for most of the years between 1850 and 1874, when the partnership was dissolved.” Brevet Major W. W. Chapman, who had arrived in 1847 and became assistant quartermaster in charge of the army’s steamers in April 1848, along with Charles Stillman, the Matamoros merchant, were greatly influential in promoting the river’s transportation potentials. This was engendered by the establishment of post-war military posts such as the Ringgold Barracks at Rio Grande City, Fort McIntosh west of Laredo, and Fort Duncan, once near Eagle Pass in order to protect against Indian depredations.

Chapman was also charged with the disposal of surplus army property that included riverboats. Stillman would privately own the Tom Kirkland that plied between Matamoros and Camargo. Brownsville merchants Bodman and Clark operated the steamer Laurel that twice weekly ran between Matamoros and the mouth of the river. They were also involved in lightering off Brazos Island and towing schooners across the Brazos Santiago bar for off-loading. Kelley documents the operation of 97 vessels plying the Rio Grande over a period of years ranging from 1829 until the steamboat, the Bessie, made its last voyage in 1902.

If Kenedy and Company did not already have a lock on the river’s steamboat trade, events transpiring during the Civil War clinched the deal. The river became the economic lifeline for the Confederate States of America (CSA). It was the export of cotton that provided funds for the CSA to purchase munitions and necessities to continue its fight with the Union. When the Union put in place a blockade of southern ports, the CSA used the Mexican port of Bagdad near the mouth of the river to ship cotton to European and even New York City buyers.

Most of the cotton came south from Corpus Christi across the King Ranch to Brownsville when it was transhipped to Matamoros and then to Bagdad. When, however, Union forces invaded the Valley in November 1863, mostly to interdict the cotton trade, the CSA moved its operations west to Laredo. A Union attack on Laredo was turned back by CSA forces and failed in its objective.

Because the river was an international waterway Kenedy and King simply reflagged their vessels under Mexican nationality. Cotton from Laredo was moved by wagons to Mier or Camargo thence by flatboats or steamers to Matamoros and the coast. The deep waters of the river at this time abetted the smuggling operations.