South Texas College history instructor Trinidad O. Gonzales grew up hearing of violence perpetrated by Texas Rangers against those in the Rio Grande Valley, including in his own family.

“I am a descendant of one of the victims of the matanza … which occurred from July to October of 1915,” Gonzales said. “The translation I’m using is ‘massacre.’ That was the word they used in the 1920s to described these events.”

“Life and Death on the Border 1910-1920,” an exhibit exploring the turbulent time will open at the Bullock Texas State History Museum on Jan. 23 in Austin.

Gonzales joined John Morán González, of the University of Texas at Austin; Sonia Hernández of Texas A&M at College Station; Benjamin Johnson, of Loyola University in Chicago, and Monica Muñoz Martinez of Brown University, to collaborate with the museum for the project. The colleagues, who run the website Refusing to Forget, originally set out to honor the border victims and “commemorat(e) the centennial of this period of state sanctioned anti-Mexican violence,” according to the website.

Students are surprised to learn about the Valley’s violent history, Gonzales said.

Johnson said there are some that don’t want the history taught or heard.

“The Texas Rangers, for some people, are like saints. They’re not to be, in any way, tarnished,” Johnson said. “But 100 years later, I think it’s time (to) talk about … the significance of the inclusion of Latinos and Mexicanos within the history of Texas and the United States.”

There is a reluctance to tackle dark chapters in textbooks, Johnson said.

“You need them to be written in a way that is willing to tackle controversial things and not just stick to a sanitized history,” Johnson said. “Human beings are complicated, and our history is complicated, too.”

THE HISTORY

The Rio Grande Valley became part of Texas with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. Valleyites had the option of becoming American citizens, or retaining Mexican citizenship, Gonzales said.

Hispanic land loss starts to occur in the 1870s to 1890s as a result of economics and drought. One factor was their inability to acquire credit, according to Gonzales.

“Ranching is a business. It’s not a pastime. It’s not a hobby,” Gonzales said. “It’s a serious business with a lot of money at stake.”

WIth the arrival of the railroad, Valley land becomes more valuable as it’s connected to the United States. This is a factor that contributes to the area’s transition from most ranching to commercial farming, Gonzales said.

With the railroad came Jim Crow-style segregation, Johnson said.

In 1915, a manifesto was signed with the intention of creating an independent republic separate from the United States — the “Plan de San Diego.”

Gonzales said the rebellion was a response to the increased segregation, discrimination and violence against Mexicans. The rebellion was aided by the Mexican Revolution, he said.

“There was an uprising — the last colonial rebellion against the United States by Mexicanos who were fighting over the Nueces Strip,” Gonzales said.

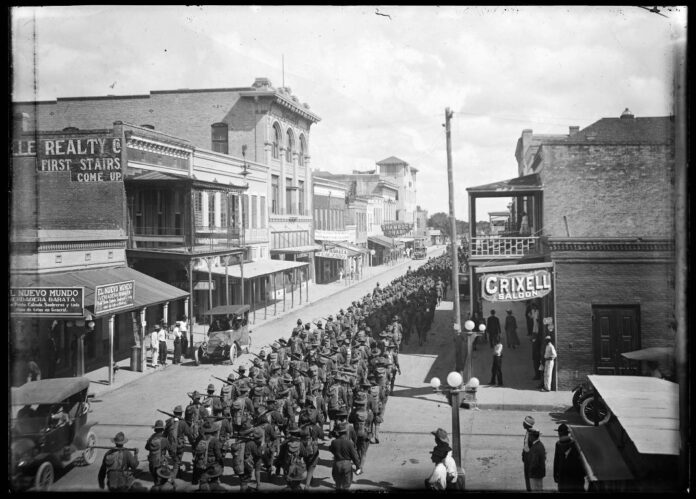

In response to that insurgency, the governor of Texas sends Texas Rangers and National Guard and the United States military presence is increased.

Brush covered much of the Valley, giving the advantage to the insurgency. Rangers and the military had difficulty tracking those familiar with the area.

“What the Rangers were good at was killing prisoners,” Gonzales said, “or people in their houses, including a 14-year-old girl in Lyford.”

When the military couldn’t track down individuals, the Anglo community created “death lists,” according to Gonzales. The term “evaporation” was used for disappeared individuals.

“That was code for ‘we killed him,’” Gonzales said.

Scholars say Rangers sometimes killed those they suspected as assisting the insurgency, and sometimes in cold blood.

Johnson described 1915 and 1916 in the Valley as some of the worst prolonged racial violence in American history.

“This is the key event in the transfer(ing) control of the most land in the Valley from Mexican to Anglo hands,” Johnson said. “It happens in this decade … and this violence allows that process to really accelerate.”

This is a turning point in the Valley’s history, Johnson said.

“This isn’t just Valley history. This is national history that we’re talking about,” Johnson said.

“It’s going to help propel what we know as the Mexican-American civil rights effort in the twentieth century.”

Johnson said many of the organizers of the 1929 Harlingen convention, where the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) emerged, came of age during the violence. Scholars trace this to the Mexican-American civil rights movement.

“Part of that history is putting a mirror to the United States and saying we have a problematic past that’s included racism … and violence against Mexican-Americans and others,” Gonzales said. “You have to understand that trauma and history in order to get to better policy and politics today. That’s just the reality.”

Gonzales said those familiar with Chicano studies know this history.

“You grew up here, you’re familiar with this history because of what your parents told you,” he said. “The reality is that the wider American public is not familiar with this history. That’s the problem.”

Gonzales said the next step would be fundraising to make the project a travelling exhibition, and to possibly make it accessible to the Valley.

“Maybe people of south Texas can take a sense of not only their importance but a sense of pride from this exhibit,” Johnson said. “I would love it if that were the case.”