MISSION — The Texas Civil Rights Project, a nonprofit organization that provides legal advocacy work, held their annual reception Thursday night where they presented a report dubbed “Land of The Free, No Home to the Brave: A Report on the Social, Economic, and Moral Cost of Deporting Veterans,” the first in-depth report on deported U.S. veterans.

Nearly 50 individuals and organizations such as La Unión Del Pueblo Unido (LUPE) and Neta RGV attended the reception, held at the National Butterfly Center. TCRP has a representation agreement with the NBC, and has provided legal support to them since preliminary planning for the Border Wall began on their property.

According to the report, between the years of 1999 and 2010, 80,000 noncitizens enlisted in the U.S. military, of which only 53,000 became naturalized U.S. citizens after their service. The most common countries of origin for noncitizen veterans are Mexico, the Philippines and Jamaica.

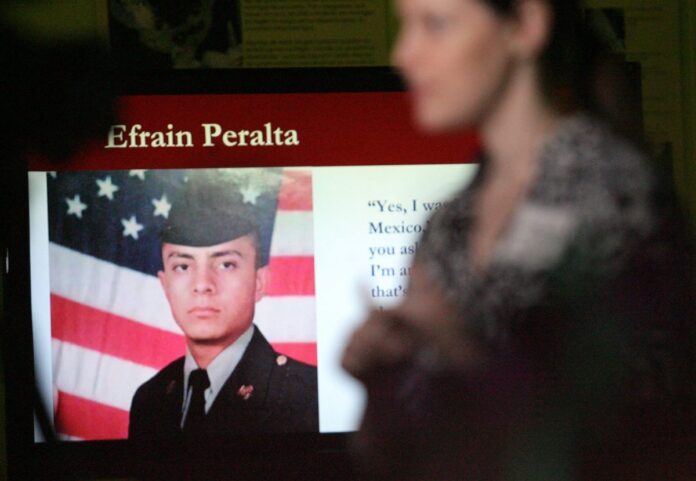

The report includes the stories of eight deported veterans, almost all of which suffered from mental illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse, which ultimately led to their arrests and deportations.

“The most astonishing thing about the report is that the reason why most of these veterans end up in the criminal justice system is specifically and directly related to their service,” said Efren Olivares, an attorney with TCRP, at the Thursday night reception.

One of the men mentioned in the report is Hector Moreno, who was born in Mexico but grew up in the United States working alongside his parents as a migrant farmworker. Shortly after earning his GED and settling in El Paso, he was drafted to serve in the Vietnam War.

Moreno was repeatedly told that he would automatically gain citizenship after his service, the report said. According to the report, neither the Army nor Air Force recruitment manuals include information about the naturalization process, and the Navy’s is brief and obscure.

After being honorably discharged, Moreno settled in South Texas where he suffered from frequent nightmares that still haunt him to this day, the report said. After a prison sentence, Moreno was deported in 2001.

According to the report, in 2008 more than 1 in 4 returning service members suffered from mental health conditions and in 2016, that number was nearly 1 in 3.

Knowing little Spanish, Moreno began street preaching, which is how he met his current wife, the report said. Despite this, Moreno still struggles to make ends meet, and hasn’t spoken to the family he left behind in 11 years.

“Some of these factors are broader problems in the ‘crimigration’ system — the intertwining of the criminal justice system and the immigration system,” Olivares said. “Those are two different systems and they exist for different reasons.”

In March 2017, U.S. Rep. Vicente Gonzalez, D-McAllen, sent an open letter to President Donald Trump urging him to fight for deported veterans, and support the Repatriate Our Patriots Act that he introduced that same month.

Gonzalez wrote an open letter to Gov. Greg Abbott in August 2017 urging him to pardon deported veterans, which “would make it more feasible for them to return to the country they love and served: The United States of America,” he wrote.

This came after Trump issued an executive order revoking the “Priority Enforcement Program” in January 2017, instructing immigration enforcement agencies to “ensure the faithful execution of the immigration laws of the United States, including the INA, against all removable aliens,” the executive order reads.

Gonzalez’s bill never made it to the house floor, and lost momentum since it was introduced. Gonzalez was not in attendance at the reception because he was voting on the budget resolution in Washington.

This story was updated to clarify that Congressman Vicente Gonzalez was not in attendance at Thursday night’s reception because he was voting on the budget resolution in Washington.