McALLEN — The last time Elizabeth Garza saw her younger brother was inside her north McAllen home.

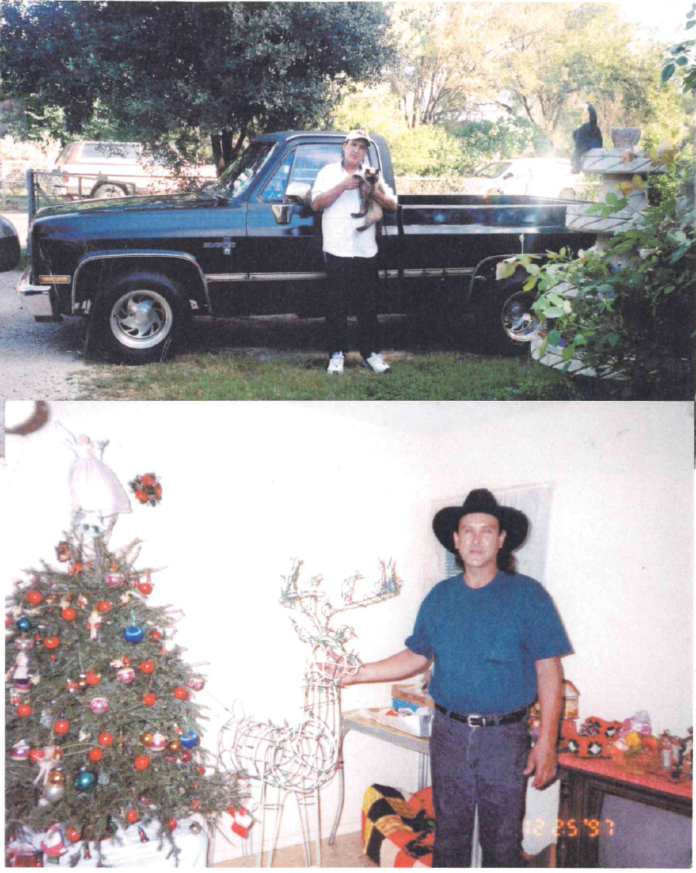

It was around Christmastime 2008 when Walton G. “Pinky” Sanchez, then 48 years old, was home to embrace his older sister and wish her a happy birthday.

Sanchez reminded her that if their mother, who shared their birthdays in the same month, was still alive they’d all be celebrating together.

It turned out that this moment would also serve as the last embrace shared between the two siblings. A week later, on the night of Dec. 23, 2008, Sanchez was shot and killed by an unknown assailant while he sat in front of a friend’s home in Mission.

Now as the ninth anniversary of his untimely death approaches, Garza is determined more than ever to share her brother’s story in hopes that someone — perhaps an individual who witnessed the shooting or knows the details but has yet to come forward — will help authorities bring Sanchez’s killer to justice.

Last Thursday, Garza recounted her brother’s happy, caring and empathetic nature. Often times, she said, he would literally give away the shoes off his feet to strangers.

Garza shared these memories inside her modest kitchen, wearing a pink polo shirt as a reminder of Sanchez’s rosy cheeks that earned him his nickname — Pinky.

He was born July 8, 1960, the baby of the family who grew up playing baseball like his father, Eduardo Sanchez, had before him. His father also had a knack for acquiring nicknames, as he was known as “El Zurdo” in addition to “Lefty.”

Sanchez had dreams of one day serving in the Navy — following in the footsteps of the two older brothers he admired so much and who served their country during Vietnam. That is until he suffered a beating at the hands of Mission police officers at the age of 13, Garza said.

Sanchez, his sisters and mother had moved to southern California in the mid-1960s and eventually returned to Mission when he was 7 years old.

But Garza said Sanchez’s hair, which he had grown accustomed to wearing long while in southern California, was like a target on his back when he returned to Mission.

Garza recounts an incident in 1973 when Sanchez was 13 years old that would change him forever.

Sanchez was beaten by Mission police officers while he was with a friend. The incident occurred after Sanchez couldn’t provide the officer with identification. Also, his hair made him appear like a “hoodlum” to police officers, Garza recounted.

“Being (that) you’re an outside kid coming into a new school, (things don’t) change here, people don’t want change,” Garza said. “He had his long hair; he looked different; they didn’t like him.”

The beating left Sanchez with a fractured skull and life-long epileptic seizures that were debilitating, creating difficulties in finding a job in his later years, Garza said.

But it also sowed the seeds of distrust in law enforcement for a young Sanchez, his sister said. She believes this explains his run-ins with law enforcement.

“He was no longer the person I knew,” she said, noting that something had changed in Sanchez given that he had long-respected law enforcement. “From that time he started going into convulsions whenever he would get too weary — he didn’t know how to control it.”

Throughout his adult years, Sanchez made a living by helping his father at the family’s mechanic shop; he would also be arrested for misdemeanors like DWI, evading arrest and misdemeanor possession of marijuana, according to public records.

Although Garza doesn’t sugarcoat her brother’s encounters with law enforcement, she said he didn’t deserve what happened to him.

Garza has encountered many things in the near decade since her brother’s shooting; dismissive law enforcement officials who would attribute Sanchez’s death to his tendency to associate with nefarious individuals.

She’s spent countless hours hassling Mission Police Department officials about her brother’s case to no avail, even at one point being informed that the case files have gone missing or been misplaced.

Garza has also filed grievances against individual officers for the record discrepancies, and she remains undeterred from speaking for her brother.

Today, police still know little and the case itself is devoid of much detail.

“On that night nine years ago while at 2020 Joanna, a gold in color car pulled up and called out to Pinky Sanchez,” read a news release Mission police issued earlier this week. “Upon approaching the vehicle (Pinky) was shot with a handgun and one single round struck Pinky causing his death. Witnesses were interviewed and rumors followed up on since that fateful night, yet here we are with still an unsolved homicide and a family wanting it resolved.

“Over the years, several leads have been investigated and suspects developed, but not enough evidence has been found to file a case against anyone. This again is where the public comes into assist. We are hoping that with the passing of time may also help a witness to feel safe enough to come forward and provide more information.”

Garza, who is still mourning her brother, has hope that in telling his story in addition to nearly a decade’s search for justice, someone will come forward with information that will lead to an arrest.

“It’s not going to bring Pinky back,” she said. “But it’s going to put somebody who’s out there with a gun, some coward that’s out there trying to murder people and getting away with it (in prison). That’s what I want. I don’t want this same tragedy that we had for it to happen to somebody else.”

Garza said she remains disappointed in how the old police administration handled her brother’s case but is optimistic that a break in the case will come in time.

Anyone with information regarding Sanchez’s case can reach the Mission Crime Stoppers at (956) 581-8477; they may be eligible for a cash reward if information leading to an arrest in this crime is provided.

Staff Writer Daniel Flores contributed to this report.