Six foreigners arrived in Tamaulipas a few months ago and now wait patiently for an opportunity to seek asylum in the U.S.; their gaze still fixed on the life they were forced to leave behind.

(Monitor photo)

“I am an indegnious Mesquita,” Donaldo, a 45-year-old indigenous Honduran whose name was changed for safety reasons, said. “We live in one of the largest departments [or state] of Honduras, Gracias a Dios.”

Donaldo and five relatives from his neighborhood left La Mosquitia for Mexico’s northern border in late September.

“A lot of indigenous people live there,” Donald said. “They’ve been natives there for over 200 years.”

Lush jungles, still nursing animals considered extinct, boasting over 180 species of plants, some critically endangered, protecting historic cultural ruins sit on the eastern edge of Honduras embracing the Caribbean coast filled with thriving aquatic life.

Life in La Mosquitia was idyllic for the nearly 150,000 people spread out among the easternmost department, one of 18 across Honduras.

Four indigenous communities who live there, the Miskitos, Tawahks, Pech and Garifunas speak their native languages, practice traditions passed down from their ancestors and live on property passed down from generations.

Donaldo and two other fellow Mesquitas — Sara, 32, and Juan, 48, whose names were also changed to ensure their safety — described their part of Honduras as land so remote, no infrastructure was built to get people around, there were no hospitals or government offices nearby.

“The property was ancestral, passed down by your ancestors,” Juan, the oldest of the group, said. “The people didn’t buy the land. They just lived off of it.”

“In December, since I was young, we would go hunting for deer,” Juan said, recalling the days of his youth. “We wouldn’t buy meat during that season, because there were a lot of animals around.”

Others worked the land to plant like legumes and bananas, while some scuba dived on the beach and in a nearby lagoon for seafood like lobsters. Large hauls of fish were ready at the market the next day.

Their livelihood changed slowly over the years when the drug trade realized the value of La Mosquitia’s geographical placement near the coast.

“Our parents, grandparents and ancestors lived, worked and grew up there,” Donaldo recalled. “But now that the drug traffickers move drugs through there, since it’s the mouth to the route up north, the wealthy drug traffickers want that ground.”

Boats and planes loaded with drugs, like cocaine, from Colombia, Venezuela and Nicaragua arrive on the coast or land in clandestine landing strips.

“The people are disappearing now. You don’t even know where they go,” Juan said.

Police will often chase after the drug loads, but residents resent law enforcement presence they’ve grown to distrust. In 2012, a passenger boat carrying 16 people on board were mistakenly gunned down by Honduran officers and a DEA agent chasing after a drug load, according to video obtained by the New York Times in 2017. Four people died, including pregnant women and a 14 year-old boy.

Most recently, a helicopter descended upon villagers on Sept. 16. Two videos shared from that day show helicopters shooting down from the air into the neighborhood where large trees provided cover while bystanders tucked behind concrete

“Sometimes drugs come in from other countries and police will go after them,” Sara explained. “It [the helicopter] got to the town and some people, who were not involved but were bathing or playing, were shot and killed. To silence them, they offered sums of money or medical help. But some people died.”

The drug traffickers on the boat fled from the coast and disappeared into the nearby neighborhood, Mirna Wood, a local activist said. Police continued their pursuit over the air shooting down in the direction they believed the traffickers fled.

By the end, four died and 16 were left injured, Mirna Wood said.

Wood is the president of the indigenous organization in the area known as Masta. The drug trade is only one of two major battles entangling the people from La Mosquitia.

A British oil company, BG Group, began eyeing their land in 2016 for gas exploration, according to Reuters. Three years later, in 2029, an Honduran newspaper, Conexihon, reported that nearly 20% of the mining and energy and hydrocarbon production concessions in Honduras were located in indigenous and black territories. The license covered 35,000 square kilometers off the coast of La Mosquitia.

Informal land agreements left many indigenous people primed to lose their home in land grab deals that followed.

“It’s like my uncle says,” Sara explained, “it’s like an inheritance that you pass down to your children, grandchildren, and like that. But they don’t have deeds. There aren’t even any offices where you can go and register a property. But the government does come with papers.”

“People from the capital will come down with documents claiming the property belongs to someone else,” Sara added. “If it’s yours, they’ll ask, show us your documents.”

Trouble started last year, Donaldo recalled. Villagers tried to fight back, but suddenly, one day in June, the 200 military men were sent down by the government.

“They said that they would give you two days to leave your home and that they would be responsible for demolishing it,” Donaldo said.

The neighborhood of about 60 families were torn down. A video taken and shared by the group shows planks of wood stacked and strewn on a muddy clearing amidst fertile forest.

“This year has been worse, the persecution. Because now they’re forcing people out of their homes,” Wood, the activist and leader of the indigenous community, said Saturday.

Just Thursday, another group was ordered out of their Central Honduran neighborhood. Although an ancestral title from 1793 registered in Spain designated the land to the indigenous community, a wealthy businessman purchased part of it in 2008, according to Conexihon.

“The military allegedly burned down the homes of some and sawed down the homes of others,” Wood said. “Since the government is an accomplice, we don’t know who to report it to.”

A report was filed with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, but people are still being chased out of their property.

“If people don’t want to sell their homes, they get killed,” Wood said.

She was elected by the indigenous community in 2019 to be their representative with the government, but she’s since denounced it as a narcostate.

The Honduran president’s brother, Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, was infamously linked to the drug trade in 2019 and sentenced to life in prison for what the prosecutor called “state-sponsored drug trafficking” in March.

That same month, an accountant placed the president himself, Juan Orlando Hernández, at the illicit meetings.

“The government is also involved in the drug trade, and people who have lived there for years are intimidated away from their home,” Wood said. “There’s no way to fight against this government.”

Wood, a native of La Mosquitia who has received death threats, is in the middle of requesting political asylum.

“They’re looking for me. I’m in hiding,” she said.

Four indigenous groups left La Mosquitia this year starting in April. Most recently, a small group of six left a few days ago.

Some go to Spain while others head to the U.S., like Donaldo, Sara and Juan.

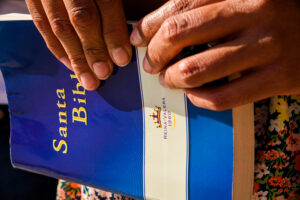

“We run into a lot of danger. That’s why we’re in constant prayer,” Juan said. Sara held her worn Bible close to her.

It will be the first time they attempt to enter the United States, the group said. They left their country not knowing what to expect.

They’ve faced discrimination along the way, even from other Hondurans who look down upon indigneous people, they said. Some were not even aware of where La Mosquitia connects to Honduras.

The group stays close hoping they will soon be able to enter the country.

Their need fell in a time when the dominant practice is to send asylum seekers back to Mexico due to the pandemic. A relative living in the U.S. is ready to give them a new home if they make it.