DONNA — U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas visited a Border Patrol detention center on Friday to announce the rapidly decreasing number of detained migrant children in their custody. The federal government is now seeing the numbers rise under another department and on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande.

For the second time since he took office, Mayorkas toured Customs and Border Protection’s Centralized Processing Center in Donna. On April 2, the facility with a maximum capacity of 500 held about 4,300 people. Of those, 3,700 were children, Chief Border Patrol Brian Hastings said Thursday during a tour granted to reporters.

“Today in this facility, rather than approximately 3,700 unaccompanied children, there are 334,” Mayorkas said, comparing the number with those detained in April. “Rather than a custody period of approximately 139 hours, they are here for approximately 24 hours.”

CBP is obligated to process migrants within a 72-hour period, but they were exceeding the three-day period as early as March. Pictures surfaced from inside the center around that time period showing overcrowded conditions. CBP released their own images emphasizing the critical limits they had reached.

A lack of bed space with the Department of Health and Human Services contributed to the bottleneck at CBP.

HHS is charged with taking unaccompanied children from CBP custody, but the unprecedented rise in apprehensions of this demographic and other logistical problems prolonged the processing time for children at Border Patrol facilities. One child told Border Patrol agents in Donna they were there for 28 days, according to Border Patrol officials who gave reporters a tour on Thursday.

Mayorkas credited the work of Border Patrol, FEMA, U.S. Immigration and Citizenship Services and HHS to meet the challenge at the border.

“The challenge remains. It is not behind us, but our plan of execution is well underway and the results are compelling,” Mayorkas said.

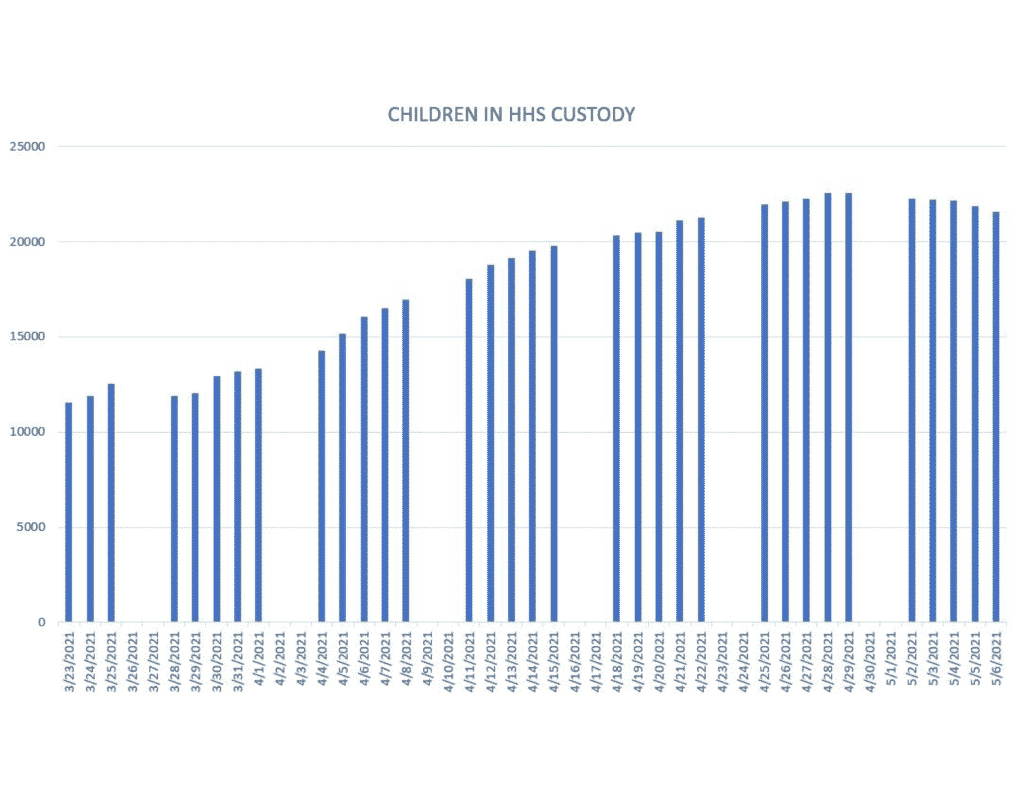

In late March, HHS’ administration for children and families began releasing data of children in federal custody across the southern border. A steep decline in the number of children in CBP custody is observed from the end of March to early May.

At its highest peak, CBP had 5,767 children in their custody across the border on March 28. By May 2, only about 600 children were in Border Patrol facilities.

On the other hand, the number of children in HHS custody increased.

According to the government data, about 11,550 children were in HHS custody on March 28. As of Friday, the number was nearly double at about 21,500.

Many of the children in CBP custody include those who come to the border with their parents. As of late January, migrant families in the Rio Grande Valley were released from federal custody to alleviate overcrowding at the Donna tents.

About 39,800 people were released into local communities, according to Hastings on Thursday. In late March, Border Patrol released families without an immigration court date en masse under an expedited process known as prosecutorial discretion. On Thursday, Hastings said he’s never been asked to do that in his 25 years with the agency.

CBP officials have attributed the release of families with children under 6 years old to the Tamaulipas shelters’ refusal to take in children of tender age.

While many were released to local U.S. communities, many others, including pregnant mothers and toddlers, were sent back to Mexico through other ports of entry in El Paso and San Diego. They are sent back, or expelled, under a federal public health code known as Title 42.

Families with children older than 6 years old are sent back to Reynosa where hundreds have now formed an encampment a block away from the international bridge.

“It’s quite a number of families,” Sister Norma Pimentel said, estimating they have up to 170 families living in a plaza.

Donated tents, tarps tied to benches or trees serve as shelter to the hundreds arriving daily. Nonprofit groups and churches are providing resources, but advocates are concerned it is enabling an encampment in an area prone to kidnapping, extortion and other crimes.

Pimentel is the executive director of Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, but Mexican immigration officials asked her to help coordinate nonprofits efforts at the Reynosa plaza.

“What the local officials are wanting to do is to provide a space next to one of the shelters, which is Senda de Vida,” Pimentel said. Once migrants are moved to safety, donations can be properly funneled to provide migrant care.

Senda de Vida, the shelter, is receiving funds from nonprofits, including Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, to expand their perimeter. A Tamaulipas agency, OIM, will provide a dome-like space to be installed at Senda de Vida. There migrants will be able to set up their tents safely and access resources like food, water, and showers, while they decide whether they will seek asylum in Mexico, temporary permission to work and stay in Mexico, or return home.

Once open, they expect it to hold up to 1,000 people, making it the largest shelter in Tamaulipas.

Title 42 — the public health authority used to expel migrants back to Mexico and which triggered some migrant parents to send their children alone into the U.S. — will stay in place until further notice, Mayorkas said.

“The use of Title 42 is driven by the public health imperative. It is not a tool of immigration. It is a tool of public health to protect not only the American people, but the migrants themselves,” the secretary said.