Last Thursday, the Mission Fire Fighters Association page on Facebook shared a post announcing the Mission Fire Department’s assistance in combating a grass fire just north of San Manuel alongside several other Rio Grande Valley fire departments.

For over five hours, the “stubborn” grass fire continued to burn.

That same day, the Mission FD fought a vehicle fire just outside the Diaz Diner’s parking lot, located at 501 E 9th St., at around 1 p.m. and a house fire on the 300 block of Bahia Street where they extracted 67-year-old Maria Zuniga out of the burning building, who later died at Mission Regional Medical Center, in the early Thursday morning.

The peak temperature that day was teetering triple digitals at a scorching 99 degrees with max wind speeds of 25 miles per hour.

And though the historic peak record for July 21 is 108 degrees, firefighters jump into sweltering heat despite the weather, a dangerous yet noble endeavor.

“Our guys work 24-hour shifts,” Assistant Chief Juan Gloria of the McAllen Fire Department said. “And so, if you have one of those big fires in the morning and you get back to the station by 10 a.m., guess what? You still don’t get out until 8 a.m. the following day and you need to be ready to respond for the rest of those hours.”

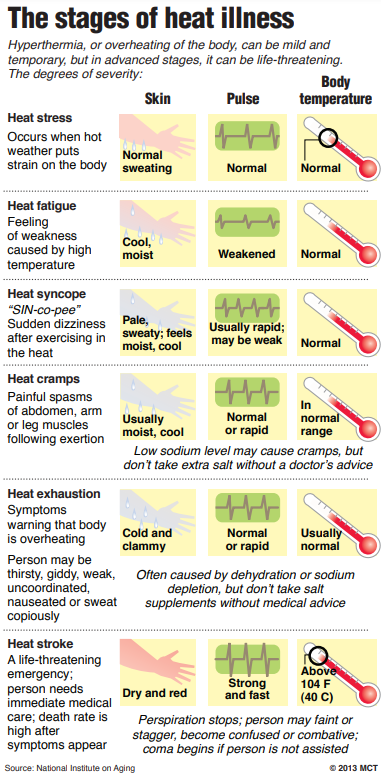

Firefighters face a myriad of dangers when combating fires but the two predominantly are heat exhaustion which could lead into heat stroke.

According to Gloria, the basic signs of heat exhaustion are dizziness, feeling faint, excessive sweating and having cold, clammy skin.

He adds that, in some extreme cases, a person experiencing heat exhaustion could feel nauseous which could lead to vomiting.

“It comes down to your pulse,” Gloria said. “Your pulse says a lot about what your condition is and so, during the heat exhaustion phase, you may experience a very rapid pulse but very weak. It’s hard to feel your pulse when under heat exhaustion.”

Fire Chief Jarrett Sheldon from the Brownsville Fire Department shared an incident that occurred last weekend where one firefighter had to be evaluated due to heat exhaustion.

“This past weekend we had a large brush fire and we were out there for multiple hours,” Sheldon said. “From that scene, we ended up getting another house on fire and that really paid a toll on our firefighters.”

The brush fire was located east of FM 802 near the landfill in Brownsville while the house fire was in the Olmito area, according to Sheldon.

The unnamed firefighter began to experience extreme muscle cramping during the house fire, a sign that things could take a turn for the worse.

Gloria says muscle cramps are one of the final indicators that one’s hydration is very low and the body is exhausting any liquids available through sweating.

“That’s when you’re ready to cross the line to heat stroke,” Gloria said. “Heat stroke can be a life-or-death situation for any given person.”

Gloria explains that once a person reaches that level, the person may lose consciousness and be completely out of their senses, experience throbbing headaches and in most extreme cases, the person may even stop sweating.

A person sweats when they heat up in order to keep the body cool. If a person stops sweating, they lose that protection and the body continues to heat up and dry once their temperature reaches 102 or 103 degrees.

“When it comes to the pulse, contrary to the heat exhaustion in this case, your pulse will continue to be really fast but it will be a very strong pulse,” Gloria said. “You will be able to feel it easily because your heart is just trying to pump out anything that is left.”

Fortunately for the unnamed Brownsville firefighter and the many who have experienced heat exhaustion, as it is a common occurrence for firefighters, the departments have systems in place to help them stay cool and hydrated whenever they’re fighting a fire.

“When we do respond to incidents, we have it in our protocols for rehabilitation during the fire meaning you put in a certain period of time and then you rehab yourself with water, peeling off your gear and cooling down,” Edinburg Fire Chief Shawn Snider said.

“Also, monitoring vital signs to make sure that the impact of the firefighting itself, coupled with the super heat that we’re experiencing, can be managed by keeping the body condition maintained during the activity.”

When fighting large fires, fire departments set up cooling stations stocked with water, and in some cases air conditioning, to maintain their personnel’s body conditions as they take shifts between fighting and cooling down, a tactic they implemented during the recent Don-Wes Flea Market fire.

Across the board, the number one way to combat heat exhaustion is to stay hydrated. It’s what firefighters do before, during and after their heroic call to action.